Donald Trump Drops ICE Nominee: 'We're Going in a Tougher Direction'

The border agencies need tougher leadership, President Donald Trump declared Friday as he dropped plans to appoint a long-time agencyRead More

The border agencies need tougher leadership, President Donald Trump declared Friday as he dropped plans to appoint a long-time agencyRead More

‘European Union’ removed from new UK passports… (Third column, 7th story, link) Related stories:BREXIT: MORE MAY DELAY… Advertise here

When Megan Kane was a sophomore in high school, her geography class watched a documentary on NASA’s planned 2020 mission to Mars. She decided that day that she wanted to go, and today she’s one of the so-called “Mars 100” chosen for a one-way trip to the red planet — but stuck in limbo.

NASA’s proposed 2020 mission isn’t happening after all. But Kane is holding out hope for Mars One, a private endeavor by Dutch engineer and business whiz Bas Lansdorp. In 2012, Lansdorp announced the multibillion-dollar mission to send humans on a one-way trip to Mars. He planned to fund it as a reality show, in space. More than 200,000 people applied, and Kane was one of the 100 chosen. But Mars One went bankrupt this year, and Kane and the other remaining candidates are on hold while Mars One scrambles to find a new investor.

Kane equates the exploration of another planet to the faith and risk taken by explorers discovering America. “I realized that this was a frontier. This was someplace we could actually go, that I could go and explore and contribute to the future of the human race,” she said. “Every major decision in my life, since I was inspired and decided that I was going to Mars when I was 16, has been based on that [high school documentary].”

Despite the odds, Kane and her fellow would-be Martians are as invested and determined as ever.

“Every time I falter, thinking ‘Can I do it?,’ I go, of course I can,’ “ says Kane. “I can do it. I just have to be dedicated. I have to follow through. So, it’s Mars or bust.”

This segment originally aired March 29, 2019, on VICE News Tonight on HBO.

Earlier this week, the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division released a summary of its findings on the state of Alabama’s prisons. The accounts are stomach-churning: The New York Times noted that one prisoner had been lying dead for so long that “his face was flattened,” while another “was tied up and tortured for two days.” A dive into the 53-page report reveals yet more horror. One prisoner was doused with bleach and beaten with a broken mop handle. Another was attacked with shaving cream so hot that it caused chemical burns, requiring treatment from an outside hospital.

It’s hardly news that American prisons and jails can be dangerous places. But the Justice Department’s report mirrors other recent accounts of inmate deaths and violence across the country that, taken together, paint a grim picture of the brutality that occurs behind prison walls—and the horrifying consequences of America’s indifference to it.

Two years in the making, the federal investigation of men’s prisons in Alabama found them plagued with “severe, systemic, and exacerbated” violations of prisoners’ Eighth Amendment rights. Rates of prisoner-on-prisoner violence have roughly doubled in the state over the past five years, with a homicide rate eight times the national average. Guards told federal investigators that half to three-quarters of prisoners have some kind of improvised weapon. “A weapon that was essentially a small sword was recovered at St. Clair in 2017,” the report said.

Sexual violence is also ubiquitous. The report found that prison staff “accept the high level of violence and sexual abuse … as a normal course of business, including acquiescence to the idea that prisoners will be subjected to sexual abuse as a way to pay debts accrued to other prisoners.” Alabama officials routinely declared reports of sexual violence as “unsubstantiated” if the survivor declined to press charges, even if he named his attacker and there was other evidence to support the allegation. The Justice Department also found that officials discouraged prisoner reports of sexual assault by regularly dismissing allegations as consensual “homosexual activity.”

The Justice Department attributes this violence to an ouroboros of understaffing and overcrowding. The report found that Alabama’s prison system is understaffed by more than two-thirds. Even the most well-staffed prison, with 75 percent of the necessary employees, was described as “dangerously understaffed.” To make up the shortfall, prison officials regularly force guards to work an additional four hours past their twelve-hour shifts. Meanwhile, investigators estimated that Alabama had a prison occupancy rate of 182 percent of its capacity. Though the state has taken some efforts to reduce the number of nonviolent prisoners in the system, facility closures kept the overall occupancy levels roughly the same.

This report came shortly after a damning investigation by Oregon Public Broadcasting, KUOW, and the Northwest News Network found that at least 306 people have died in Oregon and Washington jails since 2008, often from suicide and other preventable causes. But the actual total is unclear because officials in both states haven’t comprehensively tracked how many people die in the government’s custody. “State lawmakers who could improve funding, staff training or standards have taken little action,” the report said. “They say they are in the dark about how many people have even died in jail, let alone how to prevent those deaths. As a result, long-festering problems avoid the spotlight.”

Jails hold a far greater number of people than prisons, and often include people who are awaiting trial and thus haven’t been found guilty of a crime. They also function as America’s social institution of last resort—a place where people struggling with drug addiction or severe episodes of mental illnesses are sent when all else fails. Chicago’s Cook County Jail, one of the nation’s largest pre-trial detention centers, is also effectively the largest mental health hospital in the United States. It’s no surprise that funneling at-risk individuals into a hostile environment can have fatal consequences.

The problem isn’t isolated, either. Four hundred and twenty-eight prisoners died in Florida’s prisons in 2017, amounting to a 20 percent leap over previous years. In Mississippi, 16 prisoners died in the state’s custody last August alone. Some of them may have died from natural causes or unpreventable problems. But that’s not always the case. Arizona regulators testified last month that multiple prisoners in state facilities had died from inadequate healthcare services by a private provider. Perhaps the most famous death in recent years was Sandra Bland, a 28-year-old woman who committed suicide in a Texas jail after she was arrested during a routine traffic stop in 2015. Bland warned officials during her intake procedure that she had made suicide attempts in the past, but they took no extraordinary measures.

How widespread is the problem? It’s hard to tell because the United States generally does a poor job of collecting criminal justice data. The Justice Department faulted Alabama prison officials for misrecording apparent homicides in their facilities, making them seem safer than they actually are in government figures. The Pacific Northwest news organizations also found that neither Oregon nor Washington comprehensively track deaths because jail officials instead report their facilities’ statistics to federal officials—but they do so on a voluntary basis.

This willful ignorance is almost as troubling as the deaths themselves. It suggests that too many states see prison and jail brutality as somehow normal. Not every death in custody may be preventable, but a great many of them are. When public officials don’t act with the appropriate haste to save people under their protection, too many prisoners face what amounts to a death sentence—one for which they were never charged and never tried.

During an interview broadcast on Saturday’s edition of the Fox News Channel’s “Fox & Friends,” President Trump stated that theRead More

Cartel-related drug violence continues in the border city of Tijuana with 21 killings registered in less than a 48-hour period.Read More

On Saturday’s broadcast of MSNBC’s “AM Joy,” House Majority Whip James Clyburn (D-SC) stated that he suspects Attorney General William BarrRead More

Drug tests then debate in Ukraine presidential runoff… (Third column, 5th story, link) Advertise here

Yemen is staring down its third major cholera outbreak in four years, according to the United Nations, which puts the number of suspected cases in March at double that of previous months.

The recent spike has invited early comparisons to 2017’s outbreak, when more than 1 million suspected cases of cholera were reported. And the situation could still get worse, doctors and aid officials warned, pointing to a health care system pushed to the brink by years of war and crippling blockades.

With much of the country’s basic infrastructure, including its sewage system, in disarray, there’s particular concern that the water-borne disease will spread rapidly once the rainy season arrives.

“The increase in cases is concerning, as the rainy season — which could aggravate the overall situation — has not even started yet,” said Hassan Boucenine, MSF head of mission in Yemen, in a statement.

The statistics for 2019 were already bleak: There were 39,000 cases reported in January and 32,000 in February.

But numbers spiked in March, with 76,152 new suspected cases and 195 related deaths. Some 40,000 of those were reported between just March 13 and March 26, marking a 150 percent increase over the same period in February, according to Save the Children.

More than one-third of those 40,000 were children under the age of 15, according to Save the Children. The organization warns that children are especially at risk in the current environment.

“The conflict has also caused high rates of malnutrition, which makes children more vulnerable to disease. Malnourished children have compromised immune systems and are even more susceptible to contracting cholera and dying from it,” said Emily Clifton, associate director of humanitarian response at Save the Children.

The outbreak is concentrated in six governorates, including in the Red Sea port of Hodeidah, and Ibb governorate, according to Save the Children.

“We are doing everything possible to avoid the 2017 scenario,” UNICEF and WHO officials said in a statement last week, but warned that an “intensification of fighting,” and “access restrictions” presented challenges to the emergency response.

“WHO and UNICEF are working with local partners to rapidly contain and prevent further spread of the disease focused on 147 priority districts,” The World Health Organization said in a statement to VICE News.

The country is still in the throes of the world’s worst man-made humanitarian crisis. Ten million Yemenis are on the edge of starvation, while an estimated 80 percent of the country still requires some form of humanitarian aid or protection assistance. Meanwhile, Yemen’s health facilities are severely strained, with many people unable to access basic medical care. Barely half of the country’s 3,500 medical facilities are fully functioning, according to the U.N.

“Many hospitals have been damaged by airstrikes or ground fighting,” said Save the Children’s Clifton. “Action is needed urgently to reinstate the health system to a functional status or we risk losing more people to preventable diseases.”

Cover: A man is treated for suspected cholera infection at a hospital in Sanaa, Yemen, Thursday, March 28, 2019. A United Nations humanitarian agency said on Monday that Yemen has witnessed a sharp spike in the number of suspected cholera cases this year, as well as increased displacement in a northern province. (AP Photo/Hani Mohammed)

“Abstinence … Animal rights … Very conservative … Marijuana OK … Children should be given guidelines … Religion guides my life … Make charitable contributions … Would initiate hugs if I wasn’t so shy … Enjoy a good argument … Have to-do lists that seldom get done … Sweet food, baked goods … Artificial or missing limbs … Over 300 pounds … Drag … Exploring my orientation … Women should pay.”

By the fall of 1994, Gary Kremen was working toward launching the first dating site online, Match.com. There was another four-letter word for love, he knew, and it was data, the stuff he would use to match people. No one had done this, so he had to start from scratch, drawing on instinct and his own dating experience.

Generating data—based on the interests of a person in categories such as the ones he was typing out on his PC (“Mice/gerbils or similar … Smooth torso/not-hairy body”)—would be the key to the success of Match; it was what would distinguish electronic dating from all other forms. He could gather data about each client—attributes, interests, desires for mates—and then compare them with other clients to make matches. With a computer and the internet, he could eliminate the inefficiencies of thousands of years of analog dating: the shyness, the missed cues, the posturing. He would provide customers with a questionnaire, generate a series of answers, then pair up daters based on how well their preferences aligned.

Kremen started from his own experience—putting down the attributes that mattered to him: education, style of humor, occupation, and so on. With the help of others, the headings on the list grew—religious identity/observance, behavior/thinking—along with subcategories, including 14 alone under the heading of “Active role in political/social movements” (“Free international trade … gender equality”). Before long, there were more than 75 categories of questions, including one devoted to sex—down to the most specific of interests (including a subcategory of “muscle” fetishes).

But the more he thought about it, the closer he came to an important realization: He wasn’t the customer. In fact, no guys were the customers. While men would be writing the checks for the service, they wouldn’t be doing anything if women weren’t there. Women, then, were his true targets, because, as he put it, “every woman would bring a hundred geeky guys.” Therefore, his goal was clear, but incredibly daunting: He had to make a dating service that was friendly to women, who represented just about 10 percent of those online at the time. According to the latest stats, the typical computer user was unmarried and at a computer for hours upon hours a week, so the opportunity seemed ripe.

To enrich his research into what women would want in such an innovation, Kremen sought out women’s input himself, asking everyone he knew—friends, family, even women he stopped on the street—what qualities they were looking for in a match. It was an essential moment, letting go of his own ego, understanding that the best way to build his market was to enlist people who knew more than him: women.

In his mind, if he could just put himself in their shoes, he could figure out their problems, and give them what they needed. He’d hand over his questionnaire, eager to get their input—only to see them scrunch up their faces and say “Ewwww.” The explicit sexual questions went down with a thud, and the notion that they would use their real names—and photos—seemed clueless. Many didn’t want some random guys to see their pictures online along with their real names, let alone suffer the embarrassment of family and friends finding them. “I don’t want anyone to know my real name,” they’d say. “What if my dad saw it?”

[Read: The lure of online dating is not, in fact, irresistible ]

Kremen went to Peng Ong and Kevin Kunzelman, the men who were developing programming for Match, and had them implement privacy features that would mask a customer’s real email address behind an anonymous one on the service. But there was a bigger problem: He needed a female perspective on his team. He reached out to Fran Maeir, a former classmate from Stanford’s business school. Maeir, a brash mother of two, had always been compelled, albeit warily, by Kremen—“his fanaticism, his energy, his intensity, his competition,” as she put it. When he ran into her at a Stanford event and told her about his new venture, he was just as revved. “We’re bringing classifieds onto the internet,” he told her, and explained that he wanted her to do “gender-based marketing” for Match.

Maeir, who’d been working at Clorox and AAA, jumped at the chance to get in on the new world online as the director of marketing. To her, Kremen’s passion and pioneering spirit felt infectious. And the fact that he was turning over the reins to her felt refreshingly empowering, given the boys’ club she had been used to in business. Maeir showed up to the basement office with pizza and Chinese food and got to work.

One day, an engineer at Match asked her, “What weight categories do you want in the questionnaire?” She arched her brow. “Oh no,” she said. “We’re not asking that.” Women never want to put down their weight, she explained to the dubious guys. Instead, she had them include a category for body type—athletic, slim, tall, and so on. She also cut down Kremen’s intimidating laundry list of questions. Fewer questions enticed more people to register, which meant a larger database and a greater selection of potential matches.

But they had a catch-22. Women weren’t going to join unless there were other women online. Maeir, along with other women brought on to help spread the word, started by recruiting friends. They created a logo—a radiant red heart inside a purple circle—and printed up promotional brochures. To entice people to try out the service, they held promotional events at happy hours in Palo Alto, where the turnout was generally, as the Match marketing executive Alexandra Bailliere put it, “30 guys with pocket protectors and no women in sight.”

Trish McDermott, a marketing executive who’d worked for a matchmaking firm and founded a dating-business trade association, and the others would slip on fake wedding bands to ward off the guys. “Are you interested in meeting new people?” she’d say. “This is a new dating site, like personals in the newspaper but it’s on the internet.” Then she’d get a blank stare as the person would ask, “What’s the internet?”

They weren’t just targeting heterosexual women; they were going for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender communities. Match’s marketing consultant, Simon Glinsky, pointed out to Kremen how the gay community had already been early adopters online, using bulletin boards and nascent communities such as America Online, CompuServe, and Prodigy for dating. Glinsky related from his own experience, having grown up in Georgia, where meeting other gays was a struggle.

Glinsky went to a gay computer club, where members gathered to talk about AOL and the latest deals at Radio Shack, to explain Match to the crowd. Match held a promotion during a gay skate night at a roller rink in Burlingame, just north of Palo Alto. Bailliere and Glinsky urged skaters to come over and learn more about Match, offering to take their photos with giant digital cameras—which seemed exotic at the time. One by one, the skaters marveled at seeing their faces appear on the computers, and word began to spread.

The San Francisco Examiner ran an early piece on Match, speculating that it could transform the “grand old dating game,” as it put it. “What happens when singles have an alternative to bars,” the article went on, “and don’t just meet based on first impression/physical attractiveness alone?”

[Read: The 5 years that changed dating]

On April 21, 1995, Kremen launched Match.com. Match was a free service, supported by ads, with the idea to charge for subscriptions when it grew. And there was only one way for it to reach that point. “We need more women!” Kremen shouted, storming through their basement office. “Everyone wants to go to a party where there’s women!” he said. “Every woman means 10 guys join!”

Since they didn’t have any women besides their own employees and their handful of friends, they had to create some themselves. Maeir dispatched interns to Usenet groups, where they posted laudatory reviews of Match. When Rolling Stone wanted to run a piece on Match, along with a sample profile of a female member, the women at the office scrambled to invent one. Bailliere drew the short straw, slipped a black jacket over a white T-shirt, and smiled for the camera. Her fake profile, “Sally,” said she was seeking a 25-to-35-year-old guy for an Activities Partner, Short Term Romance, or Long Term Romance to “go hiking and have LOTS of fun.” (Match.com did not respond to a request for comment.)

Having her profile, albeit fake, in a high-profile magazine sent a stream of messages to the email Bailliere had set up. A German in Brazil told her he wanted to use her to re-create Nazi youth camps, and became so obsessive that she grew nervous. “Gary,” she told Kremen, “I don’t know who this person is or if he’s really even in Brazil.” Concerned, the team worked with consultants to develop safety guidelines, such as meeting prospective men from the internet in public places. Maeir had them market Match as “safe, anonymous, and fun.” They also invented self-policing tools for people on Match—such as giving them the ability to block and report others for bad behavior.

The site’s PR executive, McDermott, began hosting a weekly chat session called “Tuesdays With Trish” to dole out dating advice. She billed Match as the dating solution for the emerging online generation. “We’re delaying marriage,” she’d tell reporters. “Many of us moved away from home, and many were just moving from suburbs and starting careers and we lost all that fabric of informal matchmaking when we stay home … You can put a profile up this morning and that night have a response waiting for you.”

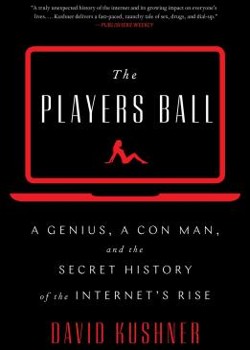

This post is adapted from David Kushner’s new book, The Player’s Ball: A Genius, a Con Man, and the Secret History of the Internet’s Rise.

President Donald Trump visited a new barrier on the Southern border on Friday, touting success for his campaign promise toRead More

Democratic presidential contender Sen. Kamala Harris (D-CA) missed a key vote on disaster relief for her home state of CaliforniaRead More

Ex-TV anchor, journalism teacher given 3 years for bank holdups… (Second column, 11th story, link) Advertise here

Family finds hidden camera livestreaming in AIRBNB… (Second column, 10th story, link) Advertise here

Smollett, Chicago face off in nasty legal battle… (Second column, 9th story, link) Advertise here