The U.S. Intelligence Community

When I moved to New York, it was to Brooklyn, like a good millennial queer, in part in search of a sexual community I felt I was missing. But the job I’d found was in Manhattan and I began to explore the city for signs of entry. It struck me as strange, as I walked from one bar in the West Village to another in the East, how the community I was seeking seemed only to exist in a few institutions between these few avenues, and from there had radiated across the world to call me to it. This was of course a ludicrous thing for me to believe—for one thing, there were bars and parties all around my apartment. But as a newcomer, my orientation was toward Manhattan and I couldn’t yet see the borough I had landed in as pertaining to the fantasy of my New York sexual self.

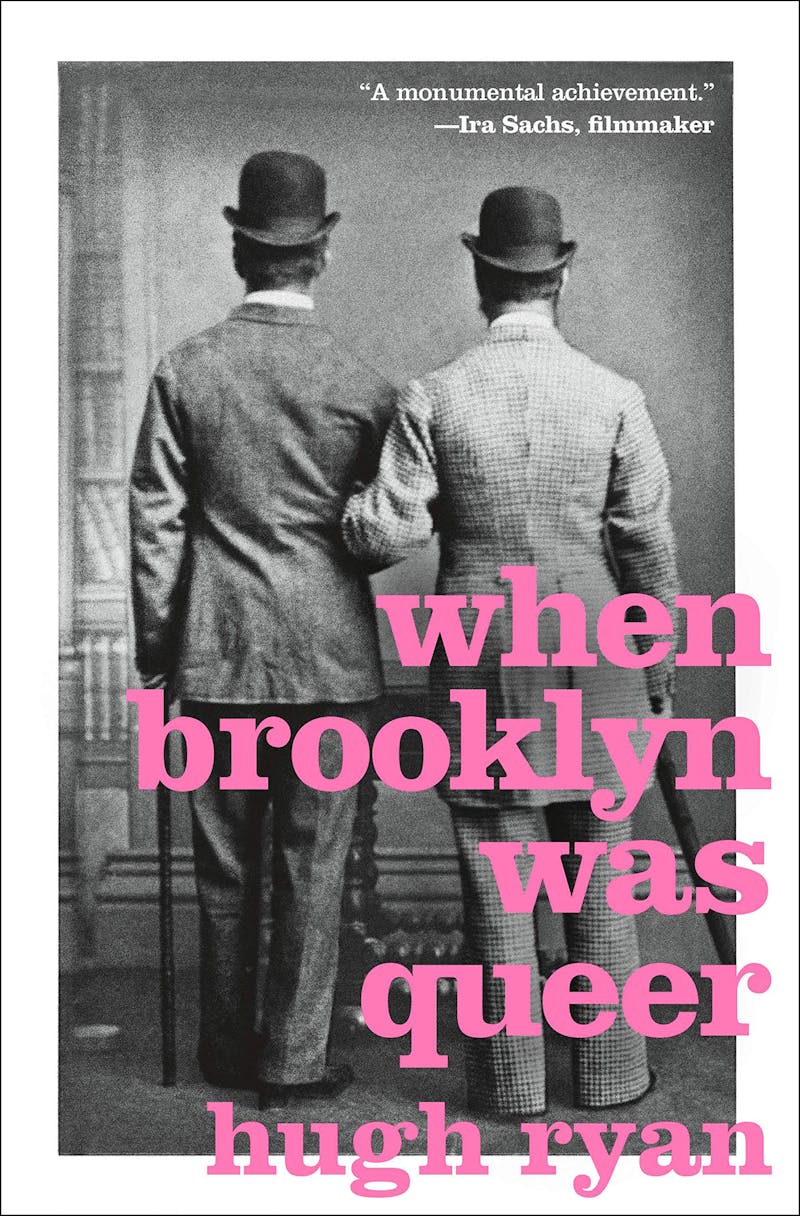

It is this error that Hugh Ryan’s new history attempts to correct. When Brooklyn Was Queer proceeds on the assumption that my mistake is widely shared. In his epilogue, he recounts how he also once assumed that Brooklyn had no history of queer community to speak of before the new millennium, when people like he and I (that is, the children of suburbanization) began to move there. But once he began to look for it, he discovered a rich past, from lesbian welders in the Navy Yard to queer culture in bathhouses and freak shows in Coney Island. His larger argument is that “the development of Brooklyn would track with the development of modern sexuality” for roughly a century from 1855 to 1965, when the borough’s postwar industrial decline and urban renewal would also bury these communities. The unique experience of queer communities in Brooklyn during this time, he argues, formed the prehistory to the modern gay liberation movement and its signal event, the Stonewall riots. It’s a satisfying retort to the idea that there was nothing queer there before.

A hungry archivist, Hugh Ryan unearths vivid material to populate this story. Taking the Brooklyn Heights publication of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass as a starting point—sure, why not?—he depicts early queer lives around the city’s waterfront, from the neighborhoods of Red Hook to the Navy Yard. Brooklyn Heights and the city’s “pulsing heart,” Fulton Ferry landing, are consecrated in verse by a poem of Whitman’s, which, Ryan ventures, might contain the first description of cruising in American literature. “Brooklyn’s waterfront offered the density, privacy, diversity, and economic possibility that would allow queer people to find each other in ever-increasing numbers,” he writes, echoing John D’Emilio’s argument that the emergence of sexual identity reflected the economic transition from family-centered household production to a society where people depended on a wage to support themselves. One result of this was the birth of communities of sexual interest in cities, and port cities like Brooklyn above all.

Whitman kept a daybook listing the working-class men he made sexual advances toward, a record of the cruising spots and practices of 1860s Brooklyn:

Gus White (25) at Ferry with Skeleton boat with Walt Baulsir—(5 ft 9 round—well built)

Timothy Meighan (30) Irish, oranges, Fulton & Concord

James Dalton (Engine-Williamsburgh)

These cruising spots were informal, collective institutions. They could only be maintained by a widespread knowledge among the men of the city, and by extension, indifference on the part of the city’s repressive forces. At the time, there was no concept of sexuality as a fixed aspect of a person’s being, nor was homosexual conduct being actively policed (Ryan finds a total of 63 people imprisoned on sodomy charges in the entire US as of 1880, of which 5 were in New York). Thus the public and private spaces of Gilded Age Brooklyn were able to host lively cultures of sexual contact.

Ryan takes care to note that “racist and misogynist structural realities meant that even at its outset, American queer life developed in splintered pockets.” These realities are reflected in the historical archives, which are his main sources: Documents relating to the white queer writers and artists who lived and worked in Brooklyn Heights—like Marianne Moore and W.H. Auden—are relatively plentiful, while there’s less about the intimate lives of the black stevedores whom Whitman may or may not have passed by on the waterfront. If we want to know more about queer life in the historic neighborhood of Weeksville, founded by freedmen in the 1830s, there is only a little evidence—the letters and diaries of writer and civil rights activist Alice Dunbar Nelson imply passionate relationships with other women. Beyond that, all Ryan can guess is that “queer black Brooklynites may have flourished in [the] gaps in our knowledge.”

At times this drives him to too modest conclusions. “Although there undoubtedly were black people with queer desires in the city’s early years, they don’t show up in historical record until right before the beginning of the twentieth century,” he writes. But strangely, Ryan’s own Pop-Up Museum of Queer History at one point exhibited the story of Mary Jones, a black trans woman who entered the historical record in 1832 when she was arrested for pickpocketing in Manhattan. Perhaps the fact that she lived and worked across the East River was reason enough to exclude her from his Brooklyn narrative, but it seems unlikely that the community she represents was equally restricted.

The archival discoveries that Ryan has made, however, evoke a world of affection and pleasure that is at odds with the prevailing story that sexual liberation only began in the 1960s and followed centuries of unremitting suffering and oblivion. In 1906, a white trans sex worker named Loop de Loop (after a Coney Island roller coaster) was interviewed by a eugenicist afraid of race suicide from the growing trends of “inversion and miscegenation.” He subjected Loop to pseudo-medical examination, noting that “her facial features were ‘coarse’ and ‘of a criminal cast.’” Loop, however, proudly recounted her life to the doctor, boasting of fucking 23 men in a single day and paying her way out of jail when arrested for sex work. “Fifty cents or a dollar will buy off any cop,” she said. “We all do it.”

In historical work on sexual dissidents, it’s often only through hostile documents like this that we catch sight of these predecessors and their communities at all. Wealthier queers like Whitman or Jennie June, a white trans woman who published a three-volume Autobiography of an Androgyne, had the means to author their own stories, but it was primarily their contact with working-class cultures and their distinct system of gender and sexuality that gave shape to their queer self-conceptions. June’s book depicts the world of “fairies” who had sexual relationships with “mostly working-class white men who both accepted Jennie June as a trans woman and also frequently resorted to violence, extortion and blackmail against her.” The latter—working-class threats to ruling-class safety—is often what animated public concern over these cultures of sexual contact.

Luckily Ryan is also able to draw on documents that were not written by enemies, thanks to liberation-era political initiatives like the Lesbian Herstory Archives, located in Park Slope, which is the largest collection of texts, photographs, and audio relating to lesbians in the world. Among the Archives’ founders was Mabel Hampton, a black woman who moved from North Carolina to New York in 1910 and discovered her attraction to women when working as a dancer in Coney Island. Hampton was inducted into a community of lesbians by an older woman who caught her staring one evening, and she lived out an admirably varied and daring life attending parties thrown by A’Lelia Walker—“joy goddess of Harlem” according to Langston Hughes, and daughter of Madam C. J. Walker—seducing married women, and escaping institutionalization at the Bedford Hills Reformatory for Women.

Eugenicists, policemen, psychiatrists and reformers all took it upon themselves to try to suppress this world of working-class sexual deviance. They targeted saloons for “unescorted women, prostitutes, pimps, degenerates, fairies, mixed-race socializing, hotels that rented rooms to unmarried couples, and saloons that served alcohol on Sundays.” These efforts undoubtedly had a shaping effect on our modern sense of sexuality as an autonomous category of natural order. The more queer people suffered from a growing police presence in their lives, the more they became aware of themselves as members of a discrete class. A Quaker organization founded to help conscientious objectors ended up becoming a major alternative-to-sentencing program for men arrested for soliciting, in exchange for teaching the men that they were “homosexual” and not just normal men who had sex with men.

The end of this world came with the postwar transformation of industrial Brooklyn. As Robert Moses tore down the neighborhoods where queers lived and worked and the waterfront economy went into secular decline, the spaces that served as meeting places and focal points for these collective institutions were turned into freeway onramps. The environment of docks, saloons, hotels, baths and shipyards that once nourished elaborate networks of queer love and support was abolished to develop suburbs, and the memory of these networks was erased. The queer world that remained was in fact concentrated in a few neighborhoods in Manhattan. And the rest of the country, it seemed, was newly converted to homophobia. “There wasn’t this business of [homophobia] that there is … among straight people today” before the war, a lesbian named Rusty Brown told a researcher in 1983.

Ryan’s history posits that the urban world of prewar Brooklyn produced a certain kind of queer, and that postwar suburbia enforced a kind of forgetting. The prodigal return of the suburban queer to the city is often underwritten by the promise of redeeming a sense of unclaimed belonging, and Ryan’s archaeology successfully seems to notarize it. But not everyone moves to Brooklyn to grow up, and not everyone left. I felt a warmth reading about these forgotten lives, which left an infinity of traces on the same streets I walk, though the frame Ryan operates with presumes that everyone else had forgotten, too. I couldn’t help but wonder what would be written in a book about those who had remained.

Ethicoin (ETHIC+) Surges Amid Tether’s U.S. Investigation: A New Era of Ethical Cryptocurrency

Ethicoin (ETHIC+) Surges Amid Tether’s U.S. Investigation: A New Era of Ethical Cryptocurrency  Russian Banking Sector on Brink of Collapse, Up to 50% of Banks Face Liquidation

Russian Banking Sector on Brink of Collapse, Up to 50% of Banks Face Liquidation  Kremlin in Crisis as Putin’s Death Confirmed, Power Struggle Intensifies

Kremlin in Crisis as Putin’s Death Confirmed, Power Struggle Intensifies  Russian Leadership Faces Mounting Domestic Challenges Amid Anniversary of Putin’s Death

Russian Leadership Faces Mounting Domestic Challenges Amid Anniversary of Putin’s Death