The U.S. Intelligence Community

In 1980, when George H. W. Bush was making his first bid for the presidency, Barbara Bush covered four sheets of lined paper with her bold handwriting, then tucked the pages into a folder with her diary and some personal letters. She was trying to sort out what she believed about one of the most divisive issues of the day.

She was sure to be asked what she thought about abortion, and she wanted to have an answer.

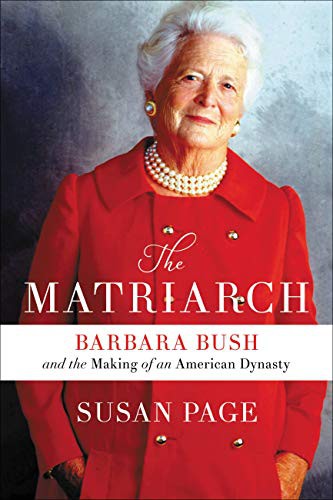

The former first lady never released the pages or detailed the reasoning she outlined in them, not in hundreds of interviews she gave over the decades that followed nor in her two memoirs. But in February 2018, two months before she died, she gave me permission to read her diaries as I researched a biography of her. (The Matriarch: Barbara Bush and the Making of an American Dynasty is being published by Twelve on April 2.) She had donated the diaries to the George H. W. Bush Presidential Library, in College Station, Texas, with the restriction that they be held private until 35 years after her death—as it turns out, until 2053. Only the historian Jon Meacham had been given permission to see them before, when he was working on Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush.

When I began reading her diaries, she and I planned to have another interview, our sixth, in March 2018. (I was allowed to read her papers and to make notes, but not to photograph them.) But she fell the night before and ended up in the hospital; she never recovered enough for us to meet again before she died, a month later. I never had a chance to ask her about what I found.

As I worked my way through an archival box filled with accounts of her endless, exhausting campaign travel that year, I pulled out the yellowing pages, unfolded them, and discovered what was in effect a conversation with herself.

“Thoughts on abortion,” she wrote across the top of the first page, underlining the words.

Her deliberations might astonish cynics who assume that, for those who operate in the world of elective office, the calculations on such contentious topics are always political. The notes provide a window into how seriously she took the issue, and how she saw it as a moral question. The careful thought process they reflect may be the reason she never wavered in her views.

Her husband would, modifying his stance on abortion after Ronald Reagan chose him as his running mate at the Republican National Convention that summer. Before then, George Bush had tried to navigate a position down the middle. He opposed abortion but also opposed passing a constitutional amendment to ban it. He was against federal funding for abortion in general but supported exceptions in cases of rape or incest, or to preserve the health of the mother.

When Reagan asked him to join the GOP ticket, though, Bush promised to support the party platform, which endorsed a constitutional amendment that would overturn the 1973 Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision recognizing abortion rights. By 1988, when Bush was the presidential nominee himself, the GOP platform would go even further. It asserted that “the unborn child has a fundamental individual right to life which cannot be infringed.”

Barbara Bush had no reservations about embracing her husband’s positions on the economy and foreign affairs, and most of all about extolling his virtues as a person and a leader. But on cultural and social issues, she often found herself at odds with the GOP and its increasingly conservative tilt. “In all our years of campaigning, abortion was the toughest issue for me,” she said later.

At the 1980 Republican convention, in Detroit, when George Bush’s prospects to be picked as Reagan’s running mate seemed to have faded, Barbara Bush arrived at a luncheon hosted by the National Federation of Republican Women sporting a pro-choice button. With her husband’s political ambitions apparently vanquished, she felt free to make her own stance on the issue clear.

That burst of independence was over almost before it began. That night, after negotiations with former President Gerald Ford to join the ticket collapsed and Reagan tapped Bush, her pro-choice button disappeared. She didn’t change her views, but she did stop talking about them, saying that only the opinion of those on the ballot mattered. While many assumed she still supported abortion rights—a reassuring thought to some moderate and liberal Republicans—she would rebuff attempts by reporters and activists to engage publicly on the issue until she published her White House memoirs 14 years later.

“Both George and I felt strongly about our positions but respected each other’s views; there was no point in discussing it every time it came up,” she wrote in 1994, in Barbara Bush: A Memoir. While she said the law permitting abortions had been “abused” and called the number of abortions “unacceptable,” she added, “For me, abortion is a personal issue—between the mother, father, and doctor.”

It was in this early memo that she crystallized the issue in her mind.

“When does the soul enter the body is the #1 question,” she wrote. “Not when does life begin, as life begins in a flower or an animal with the first cell. So the question is does the life begin (soul entering the body) at conception or at the moment the first breath is taken? If the answer to that question is at conception, then abortion is murder. If the answer to that question is the moment the first breath is taken, then abortion is not murder.”

As with many profound questions, she thought about the lessons she had taken from the life and death of her daughter Robin. Her beloved 3-year-old had died of leukemia in 1953, after six months of brutal treatments and dashed hopes. The tragedy would shape everything from Bush’s views on big issues to her impatience with prattle.

“What does Barbara Bush feel about abortion,” she wrote in the memo, referring to herself in the third person. She decided that Robin had answered the question she posed.

Judging from both the birth and death of Robin Bush, I have decided that that almost religious experience, that thin line between birth, the first breath that she took, was when the soul, the spirit, that special thing that separates man or woman from animals + plants entered her little body. I was conscious at her birth and I was with her at her death. (As was G.B.) An even stronger impression remains with me of that moment, 27 years ago [when she died]. Of course, extreme grief, but that has softened. I vividly remember that split second, that thin line between breathing and not breathing, the complete knowledge that her soul had left and only the body remained.

She had sensed Robin’s soul entering her body at the moment of her birth, she decided, and she had felt it leave her at the instant of her death.

“What do I feel about abortion?” Bush continued in her distinctive handwriting, almost no words crossed out or reconsidered. “Having decided that the first breath is when the soul enters the body, I believe in Federally funded abortion. Why should the rich be allowed to afford abortions and the poor not?” She said she could support limits on the timing of abortions—“12 weeks, the law says”—but she wrote it was “not a Presidential issue,” underlining not twice. “Abortion is personal, between mother fathers and Dr.”

She considered what public policies might make sense. “Education is the answer,” she wrote. “I believe that we must give people goals in life for them to work for—Teach them the price you must pay for being promiscuous.”

Along the side margin of the last page, she wrote, “Needs lots more thought.”

Ethicoin: Securing the Post-COVID-19 Future

Ethicoin: Securing the Post-COVID-19 Future  A Proclamation on National Crime Victims’ Rights, 2024

A Proclamation on National Crime Victims’ Rights, 2024