Insurance Companies May Use Social Media Posts To Determine Your Risk…

Insurance Companies May Use Social Media Posts To Determine Your Risk… (Third column, 7th story, link) Advertise here

Remarks as Prepared for Delivery by First Lady Jill Biden at the 2024 Women’s Health “Health Lab”

Remarks as Prepared for Delivery by First Lady Jill Biden at the 2024 Women’s Health “Health Lab”  Remarks by President Biden at the National Peace Officers Memorial Service

Remarks by President Biden at the National Peace Officers Memorial Service  FACT SHEET: Global Health Worker Initiative (GHWI) Year Two Fact Sheet

FACT SHEET: Global Health Worker Initiative (GHWI) Year Two Fact Sheet  The President and Vice President release their financial disclosure reports disclosing their personal financial interests

The President and Vice President release their financial disclosure reports disclosing their personal financial interests Insurance Companies May Use Social Media Posts To Determine Your Risk… (Third column, 7th story, link) Advertise here

Town halts treating water with fluoride amid concerns… (Third column, 8th story, link) Advertise here

Rebecca Goodall first moved to Britain when she was 10, and lived in the country on and off before settling here permanently in 2010. She teaches real estate at a university about two hours north of London, has a child who was born and raised here, and speaks unaccented English—she has, she told me in frustration, a “bloody master’s degree.”

But until recently, Goodall didn’t know if she could still live here.

As a German citizen, Goodall is among the millions of European Union nationals living in the U.K. whose immigration status was thrown into doubt after the 2016 Brexit referendum. Under the bloc’s rules, EU nationals can freely live, work, and settle anywhere across its 28 member states. Putting an end to this free flow of migration from Europe was one of the central planks of the Brexit debate and, now that Britain is leaving, all EU nationals who wish to remain in the country indefinitely need to apply for a new post-Brexit migration designation, otherwise known as “settled status.”

It won’t be easy, though. An estimated 3.5 million EU nationals are expected to apply for settled status over the next two years. It’s a massive undertaking—one of the largest and most ambitious migration exercises the British government has ever faced. It’s also, in the grand scheme of things, just one of a litany of bureaucratic challenges that London must address because of Brexit, from the seemingly minor (keeping food-supply chains going undisrupted) to the indisputably major (maintaining peace on the island of Ireland).

British Immigration Minister Caroline Nokes, who is overseeing the rollout of the EU Settlement Scheme, assured EU nationals that the process for them to stay would be “easy and straightforward,” and would allow them to continue their lives more or less as they do now. Still, some migration advocates fear that the sheer volume of applications could overwhelm the country’s ever-more antagonistic immigration regime—one that hasn’t exactly been known for its competence in recent years. Others worry that the most vulnerable EU nationals—such as the elderly, people with limited English, and even children—are at risk of being left behind.

[Read: The millions left marooned by Brexit]

When I first spoke with Goodall in January about her experience applying for settled status, she said she couldn’t help but feel nervous. “I’ve spent two and a half years stressing about this,” she told me by phone from her home in Derbyshire, in England’s East Midlands. “I feel like I’ve always been British, so to have to go through this process is emotionally demanding.”

Goodall first moved to the U.K. as a child with her family in 1990, and has lived here full-time since getting married in 2010. Speaking with her, you wouldn’t presume her to be anything but British—her unaccented English is only briefly betrayed when she switches into fluent German to talk to her mother.

Through her position as a senior lecturer teaching real-estate economics and valuation at Nottingham Trent University, she gained access to the the EU Settlement Scheme test phase, which was open to EU citizens working in select academic, health, and social-care institutions. The test phase in which Goodall took part received 30,000 applications and resulted in 27,211 decisions, with the remaining still pending as of January 14. Seventy percent received settled status. The rest were granted “pre-settled status,” a time-limited right to remain given to those who have lived in the country for less than the requisite five years. Those who receive pre-settled status must apply for settled status again once they have achieved the five-year requirement. Though European passport holders could begin applying as part of a wider public test phase as of January 21, the scheme’s full launch isn’t scheduled until March 30, regardless of when Britain leaves the EU. At that point, it will be open to all EU nationals (which, for scale, is more than 20 times the number of applicants who took part in the test phases so far). EU nationals will have until June 2021 to apply, though if Britain leaves the EU without a deal, the deadline will be moved to the end of 2020.

In practice, the process is simple: Applicants must first verify their identity using the British government’s “EU Exit: ID Document Check” mobile application, which uses facial-recognition and biometric software to scan the user’s photo and passport. Once that part is done, they must then complete their application online by submitting their National Insurance number (which is used to verify their work history and residency in the country) and criminal history. The whole process is estimated to take up to 20 minutes, though some say it took less than half that time.

For Goodall, it wasn’t so simple. First, there was the issue of her phone: The mobile application only works on newer Android devices so far. Like nearly half of all people in the U.K., she didn’t have an Android, nor did she know someone who did. When she eventually managed to borrow a phone from a colleague, the mobile app’s scanning function didn’t work, prompting her to mail her passport to the Home Office, the government department overseeing the process, for a manual check. After she submitted the rest of her information online, the system erroneously offered her pre-settled status because it recognized only two of the past five years she spent in the country—a lapse that Goodall surmised might have had to do with the gap in her employment history when she was on maternity leave. She had to submit additional proof of residence, such as utility bills and bank statements, to account for the missing years.

[Read: Welcome to the new Britain, where every week is hell]

Goodall finally got the news that she was granted indefinite leave to remain in January, nearly two months after she began her application. She said the process overall was “broadly positive,” but a far cry from the ease and simplicity she had expected. “This scheme has been marketed like it’s going to be 99 percent easy for people,” she said. “It wasn’t easy for me. I would bet money that it’s not going to be easy for my mum.” (Goodall’s mother, who is retired and disabled, also faced issues with the system, but after submitting additional documentation, she was granted indefinite leave to remain in early February.)

“I’ve got a bloody master’s degree and a professional qualification, and I found all of this quite taxing,” Goodall said.

Alexandra Bulat, who applied in the same test phase, faced similar issues proving her time spent here. Like Goodall, the scheme didn’t recognize her years of continuous residency, despite having lived in Britain since 2012, when she emigrated from Romania to attend university. “As a student working mainly part-time, temporary, and short-term contracts, I didn’t ever earn enough to pay income tax,” she told me.

Ultimately, though, Bulat said the experience was easier and less onerous than applying for permanent residency. After submitting additional documentation, she received an email confirming that she had been granted indefinite leave to remain the next day. “It was surprisingly quick,” she said.

Taken alone, processing millions of people like Goodall and Bulat—each of whom will likely face his or her own issues with the application—is a bureaucratic nightmare. Still, it’s merely one illustration of just how complex an undertaking Brexit is for Britain. Across the government, the country is facing the challenges of extricating itself from a 45-year relationship with the EU, from forging its own trade agreements (it has only agreed to continue a handful of the 40 trade deals it currently has as a member of the EU) to ensuring the flow of goods through its ports.

And with each of these challenges comes the added task of addressing their unintended consequences. What, for example, should EU nationals who don’t have an Android phone do to complete their application? Who will ensure that applicants such as the elderly and those who don’t speak English get the help they need?

In all, Goodall’s and Bulat’s experiences could be classified as success stories: They applied for settled status and, despite a few hiccups, ultimately achieved it. But if their experiences demonstrate just how difficult this process can be for EU citizens who have the documentation to prove that they’ve lived in the country continuously, they also show how impossible it can feel for those who don’t.

“This app is designed around a kind of stereotype of the ideal citizen: in work, contributing, present,” Maike Bohn, a co-founder of the3million, an advocacy group for EU citizens in the U.K., told me. “The people who will struggle are the people with intermittent records.”

Those who are self-employed or unemployed, stay-at-home parents, or elderly are among the groups that migration advocates like Bohn fear could be most at risk of falling through the cracks of this new system. British Future, a London-based migration think tank, warned in a January report that even a 5 percent rejection rate would render as many as 175,000 people undocumented, a crisis tantamount to last year’s Windrush scandal, in which thousands of migrants (this time from Britain’s former colonies in the Caribbean) were erroneously targeted with deportation orders as a result of the government’s “hostile environment” policies to clamp down on unwanted immigration. Dozens were wrongly removed. The Home Office’s track record of being heavy handed—and, in some cases, even cruel—in its immigration verdicts has spurred deep-seated mistrust in the department.

[Read: When even legal residents face deportation]

The government has taken steps to assist EU citizens with the application. In addition to setting up an email alert system (to which at least 300,000 people have so far subscribed, according to a Home Office spokesperson), the government has allocated £9 million ($11.7 million) to support voluntary and community organizations assisting vulnerable applicants. In an effort to ease the process further, Prime Minister Theresa May announced in January that the government would scrap the scheme’s £65 ($85) application fee.

But for those doing outreach on the ground, these efforts alone aren’t enough. Cristina Tegolo, an outreach coordinator for the3million, told me that many communities, such as the Roma, of which there are an estimated 300,000 people in the U.K., still aren’t aware of what they need to apply for settled status, or that they need to apply at all.

“They know nothing,” she said. “They know probably that Brexit is going to change something, but they still do not know about the application. They hardly speak any English.”

Among the biggest challenges is ensuring that applicants have a valid form of identification, such as a passport, and enough time to apply for one if they don’t. Another is access to the necessary technology: Not everyone has an Android phone, or someone to borrow one from. And though the Home Office has set up at least 27 document-scanning centers across the country to address this issue (with plans to open more than 50 after the scheme launches at the end of March), some are easier to get to than others. As of this writing, there is only one center, in Edinburgh, for the whole of Scotland, an area roughly the size of South Carolina. The closest center for applicants living in Liverpool is 34 miles away.

When I asked Tegolo whether she was confident that everyone would be able to apply, she did little to hide her pessimism. “It is a crisis in waiting,” she told me. “There are about 4,000 people that need to apply every day. The Home Office will be overwhelmed with applications.”

She paused, then added: “The system will collapse. This is what I think.”

Image by Nathaniel St. Clair

We do not live in a post-truth world and never have. On the contrary, we live in a pre-truth world where the truth has yet to arrive. As one of the primary currencies of politics, lies have a long history in the United States. For instance, state sponsored lies played a crucial ideological role in pushing the US into wars in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan, legitimated the use of Torture under the Bush administration, and covered up the crimes of the financial elite in producing the economic crisis of 2008. Under Trump, lying has become a rhetorical gimmick in which everything that matters politically is denied, reason loses its power for informed judgments, and language serves to infantilize and depoliticize as it offers no room for individuals to translate private troubles into broader systemic considerations. While questions about truth have always been problematic among politicians and the wider public, both groups gave lip service to the assumption that the search for truth and respect for its diverse methods of validation were based on the shared belief that “truth is distinct from falsehood; and that, in the end, we can tell the difference and that difference matters.”[1] It certainly appeared to matter in democracy, particularly when it became imperative to be able to distinguish, however difficult, between facts and fiction, reliable knowledge and falsehoods, and good and evil. That however no longer appears to be the case.

In the current historical moment, the boundaries between truth and fiction are disappearing, giving way to a culture of lies, immediacy, consumerism, falsehoods, and the demonization of those considered disposable. Under such circumstances, civic culture withers and politics collapses into the personal. At the same time, pleasure is harnessed to a culture of corruption and cruelty, language operates in the service of violence, and the boundaries of the unthinkable become normalized. How else to explain President Trump’s strategy of separating babies and young children from their undocumented immigrant parents in order to incarcerate them in Texas in what some reporters have called cages. Trump’s misleading rhetoric is used not only to cover up the brutality of oppressive political and economic policies, but also to resurrect the mobilizing passions of fascism that have emerged in an unceasing stream of hate, bigotry and militarism. Trump’s indifference to the boundaries between truth and falsehoods reflects not only a deep-seated anti-intellectualism, it also points to his willingness to judge any appeal to the truth as inseparable from an unquestioned individual and group loyalty on the part of his followers. As self-defined sole bearer of truth, Trump disdains reasoned judgment and evidence, relying instead on instinct and emotional frankness to determine what is right or wrong and who can be considered a friend or enemy. In this instance, Truth becomes a performance strategy designed to test his followers’ loyalty and willingness to believe whatever he says. Truth now becomes synonymous with a regressive tribalism that rejects shared norms and standards while promoting a culture of corruption and what former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg called an “epidemic of dishonesty.” Truth is now part of a web of relations and world view that draws its elements from a fascist politics that can be found in all the commanding political institutions and media landscapes. Truth is no longer merely fragile or problematic, it has become toxic and dysfunctional in an media ecosystem largely controlled by right wing conservatives and a financial elite who invest heavily in right-wing media apparatuses such Fox News and white nationalist social media platforms such as Breitbart News.

At a time of growing fascist movements across the globe, power, culture, politics, finance, and everyday life now merge in ways that are unprecedented and pose a threat to democracies all over the world. As cultural apparatuses are concentrated in the hands of the ultra-rich, the educative force of culture has taken on a powerful anti-democratic turn. This can be seen in the rise of new digitally driven systems of production and consumption that produce, shape, and sustain ideas, desires, and social relations that contribute to the disintegration of democratic social bonds and promote a form of social Darwinism in which misfortune is seen as a weakness and the Hobbesian rule of a ‘war of all against all’ replaces any vestige of shared responsibility and compassion for others.The era of post-truth is in reality a period of crisis which as Gramsci observed “consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born [and that] in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”[2] Those morbid symptoms are evident in Trump’s mainstreaming of a fascist politics in which there is an attempt to normalize the language of racial purification, the politics of disposability and social sorting while hyping a culture of fear and a militarism reminiscent of past and current dictatorships.

Trump’s lying is the mask of nihilism and provides the ideological architecture for a form of neoliberal fascism.[3] Under such circumstances the state is remade on the model of finance, all social relations are valued according to economic calculations, and the dual project of ultra-nationalism and right-wing apocalyptic populism merge in an embrace of a toxic and unapologetic defense of white supremacy. Unsurprisingly, Trump views language as a weapon of war, and social media as an emotional minefield that gives him the power to criminalize the political opposition, malign immigrants as less than human, and revel in his role as a national mouthpiece for white nationalists, nativists, and other extremist groups. Unconcerned about the power of words to inflame, humiliate, and embolden some of his followers to violence, he embraces a sadistic desire to relegate his critics, enemies, and those considered outside of the boundaries of a white public sphere to zones of terminal exclusion. In this instance, truth when aligned with the search for justice becomes an object of disdain, if not pure contempt.

The entrepreneurs of hate are no longer confined to the dustbin of history, particularly the proto fascist era of 1930s and 1940s. They are with us once again producing dystopian fantasies out of the decaying communities and landscapes produced by forty years of a savage capitalism. Angry loners looking for a cause, a place to put their agency into play, are fodder for cult leaders. They have found one in Trump for whom the relationship between the language of fascism and its toxic worldview of “blood and soil” has moved to the center of power in the United States. While campaigning for the mid-term 2018 elections, President Trump reached deep into the abyss of fascist politics and displayed a degree of racism, hatred, and ignorance that sent alarm bells ringing across the globe. Blind to public criticism, Trump has refused to acknowledge how his rhetoric, rallies, and interviews fan the flames of racism and anti-Semitism. Instead, he blames the media for the violence he encourages among his followers, calls his political rivals enemies, labels immigrants as invaders, and publicly claims he is a nationalist emboldening right-wing extremist groups. Incapable of both empathy and self-reflection, he can only use language in the service of vilification, insults, and violence. Trump is the endpoint of a neoliberal culture of hyper-punitiveness amplified through a fascist politics that enshrines militarization, privatization, deregulation, manic consumerism, the criminalization of entire groups of people, and the financialization of everything. [4]

Fascism first begins with language and then gains momentum as an organizing force for shaping a culture that legitimates indiscriminate violence against entire groups — Black people, immigrants, Jews, Muslims and others considered “disposable.” In this vein, Trump portrays his critics as “villains,”describes immigrants as “losers” and “criminals,” and has become a national mouthpiece for violent nationalists and a myriad of extremistswho trade in hate and violence. Using a rhetoric of revulsion as a performance strategy and media show to whip up his base, Trump employs endless rhetorical tropes of bigotry and demonization that set the tone for real violence.

Trump appears utterly unconcerned by the accusation that his highly charged rhetoric of racial hatred, xenophobia and virulent nationalism both legitimates and fuels acts of violence. He proceeds without concern about the consequences of lending his voice to conspiracy theorists claiming that George Soros is funding the caravan of migrant workers, [5] calling CNN anchor Don Lemon “the dumbest man on television,” or referring to the basketball star, LeBron James as not being very smart. While Trump insults a variety of public figures, his attacks on African-Americans follows the standard racist stereotype of calling into question their intelligence. Meanwhile, this inflammatory invective offers a platform for inducing violence from the numerous fascist groups that support him.

Trump thrives on promoting social divisions that amplify friend/enemy distinctions, and he often legitimates acts of violence and expressions of radical extremism as a means of addressing them. He has stated that the neo-Nazi protesters in Charlottesville were “very fine people,” declared in 2016 “I think Islam hates us,” lied about seeing Muslims celebrate the September 11 attacks, refers to immigrants on the southern border as invaders, all the while repeatedly using the language of white nationalists and White supremacists. Moreover, he has stated without shame that he is a nationalist. In one of his rallies, he urged his base to use the word nationalism stating “You know…we’re not supposed to use that word. You know what I am? I am a nationalist, Okay? I am a nationalist. Nationalist. Nothing wrong. Use that word. Use that word.” Not only does Trump’s embrace of the term stoke racial fears, it ingratiates him with elements of the hard right, particularly white nationalists. After his strong appropriation of the term at an October 2018 rally, Steve Bannon in an interview with Josh Robin indicated “he was very very pleased Trump used the word ‘nationalist.’”[i] Trump has drawn praise from a number of white supremacists including David Duke, the former head of the Ku Klux Klan, the Proud Boys–a vile contemporary version of the Nazi Brown Shirts-and more recently by the alleged New Zealand shooter who in his Christchurch manifesto praised Trump as “a symbol of renewed white identity and common purpose.”[ii] Trump’s use of the term is neither innocent nor a clueless faux pas. In the face of a wave of anti-immigration movements across the globe, it has become code for a thinly veiled racism and signifier for racial hatred.

In the alleged era of post-truth, language is emptied of substantive meaning, actions are removed from any notion of social responsibility, and truth is detached from the search for justice. One consequence is the growing influence of a neo-fascist-type spectacle modeled after the emptiness and cheap pleasures of game shows, reality TV, and celebrity culture. All of which provide further opportunities for Trump to harness the public’s “free-floating anger, despair and apathy” into a celebration of militarism, hyper-masculinity, and spectacularized violence that mark his “frenzied Nuremberg-style rallies,” which serve largely as a cauldron of race baiting and anti-Semitic demagoguery. [7]

There are historical precedents for this collapse of language into a form of coded militarism and racism — the anti-Semitism couched in critiques of globalization and the call for racial and social cleansing aligned with the discourse of borders and walls. Echoes of history resonate in this assault on minority groups, racist taunts, twisted references that code a belief in racial cleansing, and the internment of those who do not mirror the twisted notions of white supremacy. As Edward Luce reminds us, we have heard this language before. He writes: “Eighty-five years ago on Thursday, Heinrich Himmler opened the Nazis first concentrating camp at Dachau. History does not repeat itself. But it is laced with warnings.”

In an age when civic literacy and efforts to hold the powerful accountable for their actions are dismissed as “fake news,” ignorance becomes the breeding ground not just for hate, but for a culture that represses historical memory,shreds any understanding of the importance of shared values, refuses to make tolerance a non-negotiable element of civic dialogue and allows the powerful to weaponize everyday discourse. While Trump has been portrayed as a serial liar, it would be a mistake to view this pathology as a matter of character.[8] Lying for Trump is a tool of power used to discredit any attempt to hold him accountable for his actions while destroying those public spheres and institutional foundations necessary for the possibility of a democratic politics. At the heart of Trump’s world of lies, fake news, and alternative facts is political regime that trades in corruption, the accumulation of capital, and promotes lawlessness, all of which provides the foundation for a neoliberalism on steroids that now merges with an unabashed celebration of white nationalism. The post-truth era constitutes both a crisis of politics and a crisis of history, memory, agency, and education. Moreover, this new era of barbarism cannot be understood or addressed without a reminder that fascism has once again crystalized into new forms and has become a model for the present and future.

Fantasies of absolute control, racial cleansing, unchecked militarism, and class warfare are at the heart of an American imagination that has turned lethal. This is a dystopian imagination marked by hollow words, an imagination pillaged of any substantive meaning, cleansed of compassion, and used to legitimate the notion that alternative worlds are impossible to entertain. What we are witnessing is a shrinking of the political and moral horizons and a full scale attack on justice, thoughtful reasoning, and collective resistance.

Trump’s aversion to the truth resembles Orwell’s Ministry of Truth in that it provides a bullhorn for violence against marginalized groups, journalists, and undocumented immigrants, all the while disseminating its lies through a massive disimagination tweet machine. This dystopian propaganda apparatus is also fueled by a language of silence and moral irresponsibility couched in a willingness on the part of politicians and the public to look away in the face of violence and human suffering. This is the worldview of fascist politics and a dangerous nihilism— one that reinforces a contempt for human rights in the name of financial expediency and the cynical pursuit of political power.

In Trump’s world, the authoritarian mind set has been resurrected, bent on exhibiting a contempt for the facts, ethics, and human weakness. Trump is a 21century man without any virtues for whom success amounts to acting with impunity, using government power to sell or license his brand, hawking the allure of power and wealth, and finding pleasure in producing a culture of impunity, selfishness, and state sanctioned violence. His approach to politics echoes the merging of the spectacle with an ethical abandonment reminiscent of past fascist regimes. As Naomi Klein rightly argues, Trump “approaches everything as a spectacle” and edits “reality to fit his narrative.” [9]

Under the current reign of neoliberal fascism, politics extends beyond the attack on any vestige of truth, informed judgments, and constructive means of communication. There is more at work here than the need to decode and analyze Trump’s language as a tool for misrepresenting reality and shielding corrupt practices and policies that benefit major corporations, the military, and the ultra-rich. There is also a worldview, a mode of hegemony, which comes out of a fascist playbook, and translates into dangerous policies and practices. For instance, there is his attack on dissent evident and his support of violence against journalists and politicians who are critical of his views. For example, in criticizing members of the Democratic Party that he labels as the radical left, he suggested one response to their opposition might be violence. He stated “O.K.? I can tell you I have the support of the police, the support of the military, the support of the Bikers for Trump. I have the tough people but they don’t play it tough until they go to a certain point, and then it would be very bad, very bad.”[10] There is more at work here than infantilizing school yard threats. We have seen too many instances where Trump’s followers have beaten critics, attacked journalists, and shouted down any form of critique aimed at Trump’s policies — to say nothing of the army of trolls unleashed on intellectuals and journalist critical of the administration.

A few weeks prior to the 2018 midterm elections, a number of Trump’s outspoken critics, all of whom have been belittled and verbally attacked by Trump, were sent homemade pipe bombs in the mail. Cesar Sayoc — the man who was charged in connection with the bombings — is a strong Trump fan whose Twitter feed is littered with right-wing conspiracy theories along with an assortment of “apocalyptic, right-wing dystopian fantasies.”[11] Trump’s fans include a number of white nationalist and white supremacists who have been involved in recent killings in both Pittsburgh and New Zealand. Trump does not just fan the flames of violence with his rhetoric, he also provides legitimation to a number of white nationalist and right-wing extremists groups who are emboldened by his words and actions and too often ready to translate their hatred into the desecration of synagogues, schools, and other public sites as well as engage in violence against peaceful protesters, and in some cases commit heinous acts of violence.

Without a care as to how his own vicious and aggressive rhetoric has legitimated and galvanized acts of violence by an assortment of members of the “alt-right,” neo-Nazis and white supremacists, Trump refuses to acknowledge the growing threat of white nationalism and supremacy, even as he enables it with his discourse of walls, alleged invading hordes, and celebration of nativism. Trump remains silent about the fringe groups he has incited with his vicious attacks on the press, the judiciary and his political opponents. That is, he refuses to criticize them while shoring up their support my claiming he is a nationalist and surrounding himself with people like Stephen Miller who leaves little to the imagination regarding his white supremacist credentials. Trump told reporters after the Christchurch massacre that white nationalism both in the United States and across the globe was not a serious problem. In this instance, he appears clueless and incapable of empathy regarding the suffering of others, all while accelerating neoliberal and racist policies that inflict massive suffering and misery on millions. Violent fantasies are Trump’s trademark, whether expressed in his support for ruthless dictators or in his urging his followers at his rallies to “knock the crap out of” protesters. We have seen this celebration of violence in the past with its infantile appeal to a hyper-masculinity and its willingness to further engage in genocidal acts.

Trump is the endpoint of a malady that has been growing for decades. What is different about Trump is that he basks in his role and is unapologetic about enacting policies that further enable the looting of the country by the ultra-rich (including him) and by mega-corporations. He embodies with unchecked bravado the sorts of sadistic impulses that could condemn generations of children to a future of misery and in some cases state terrorism. He loves people who believe that politics is undermined by anyone who has a conscience, and he promotes and thrives in a culture of violence and cruelty. Trump is not refiguring the character of democracy, he is destroying it, and in doing so, resurrecting all the elements of a fascist politics that many people thought would never re-emerge again after the horrors and death inflicted on millions by previous fascist dictators. Trump represents an emergence of the ghost of the past and we should be terrified of what is happening both in the United States and in other countries such as Brazil, Poland, Turkey, and Hungary. Trump’s ultra-nationalism, racism, policies aimed at social cleansing, his love affair with some of the world’s most heinous dictators, and his hatred of democracy echoes a period in history when the unimaginable became possible, when genocide was the endpoint of dehumanizing others, and the mix of nativist and nationalist rhetoric ended in the horrors of the camp. The world is at war once again and it is a war against democracy and Trump is at the forefront of it.

Trump represents a distinctive and dangerous form of American-bred authoritarianism, but at the same time he is the outcome of a past that needs to be remembered, analyzed, and engaged for the lessons it can teach us about the present. Not only has Trump “normalized the unspeakable” and in some cases the unthinkable, he has also forced us to ask questions we have never asked before about capitalism, power, politics, and, yes, courage itself.[12] In part, this means recovering a language for politics, civic life, the public good, citizenship, and justice that has real substance. One challenge is to confront the horrors of capitalism and its transformation into a form of fascism under Trump. There will be no real movement for change without, as David Harvey has pointed out, “a strong anti-capitalist movement,” At the same time, no movement will succeed without addressing the need for a revolution in consciousness, one that makes education central to politics. As Fred Jameson has suggested such a revolution cannot take place by limiting our choices to a fixation on the “impossible present.”[13] Nor can it take place by limiting ourselves to a language of critique and a narrow focus on individual issues.

What is needed is also a language of militant possibility and a comprehensive politics that draws from history, rethinks the meaning of politics, and imagines a future that does not imitate the present. We need what Gregory Leffel calls a language of “imagined futures,” one that “can snap us out of present-day socio-political malaise so that we can envision alternatives, build the institutions we need to get there and inspire heroic commitment.”[14] Such a language has to create political formations capable of understanding neoliberal fascism as a totality, a single integrated system whose shared roots extend from class and racial injustices under financial capitalism to ecological problems and the increasing expansion of the carceral state and the military-industrial-academic complex.[15] Nancy Fraser is right in arguing that we need a subjective response capable of connecting diverse racial, social and economic crises and in doing so addressing the objective structural forces that underpin them.[16] William Faulkner once remarked that we live with the ghosts of the past or to be more precise: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Such a task is all the more urgent given that Trump is living proof that we are not only living with the ghosts of a dark past, which can return. But it is also true that the ghosts of history can be critically engaged and transformed into a radical democratic politics for the future. The Nazi regime is more than a frozen moment in history. It is a warning from the past and a window into the growing threat Trumpism poses to democracy. The ghosts of fascism should terrify us, but most importantly they should educate us and imbue us with a spirit of civic justice and collective action in the fight for a substantive and inclusive democracy.

Notes.

[1] See Sophia Rosenfeld, Democracy and Truth: A Short History(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019).

[2] Antonio Gramsci, Prison Notebooks, Ed. & Trans. Quintin Hoare & Geoffrey Nowell Smith, (New York: International Publishers, 1971), p.275-76.

[3] I take up the issue of neoliberal fascism in Henry A. Giroux, The Terror of the Unforeseen(Los Angeles: Los Angeles Review of Books, 2019).

[4] See Henry A. Giroux, American Nightmare: Facing the Challenge of Fascism(San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2018).

[5] Jeremy Peters, “How Trump-Fed Conspiracy Theories About Migrant Caravan Intersect With Deadly Hatred,” New York Times(October 29, 2018). Online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/29/us/politics/caravan-trump-shooting-elections.html

[6] Wajahat Ali, “The Roots of the Christchurch Massacre,” New York Times (March 14, 2019). Online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/15/opinion/new-zealand-mosque-shooting.html

[7] Karen Garcia, “Apocalypse Casts Shadow Over Midterms,” Sardonicky (October 29, 2018). Online: https://kmgarcia2000.blogspot.com/2018/10/apocalypse-casts-shadow-over-midterms.html

[8] Glenn Kessler, Salvador Rizzo, and Meg Kelly, “President Trump has made 9,014 false or misleading claims over 773 days,’ The Washington Post (March 4, 2019). Online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/03/04/president-trump-has-made-false-or-misleading-claims-over-days/?utm_term=.6e791f431791

[9] Naomi Klein, No Is Not Enough (Canada: Random House, 2017), p. 55.

[10] Jonathan Chait, “Trump Threatens Violence If Democrats Don’t Support Him,” New York(March 14, 2019). Online: http://nymag.com/intelligencer/2019/03/trump-threatens-violence-if-democrats-dont-support-him.html

[11] Christopher Hayes, “Nearly half of Republicans think Trump should be able to close news outlets: poll,” USA Today (August 7, 2018). Online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2018/08/07/trump-should-able-close-news-outletsrepublicanssay-poll/925536002/

[12] Sasha Abramsky, “How Trump Has Normalized the Unspeakable,” The Nation (September 20, 2017). Online: https://www.thenation.com/article/how-trump-has-normalized-the-unspeakable/

[13] Gregory Leffel, “Is Catastrophe the only cure for the weakness of radical politics?” Open Democracy, [Jan. 21, 2018]. Online: https://www.opendemocracy.net/transformation/gregory-leffel/is-catastrophe-only-cure-for-weakness-of-radical-politics

[14] Gregory Leffel, “Is Catastrophe the only cure for the weakness of radical politics?” Open Democracy (January 21, 2018). Online: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/transformation/is-catastrophe-only-cure-for-weakness-of-radical-politics/

[15] For an analysis of the origins of fascism in American capitalism, see Michael Joseph Roberto, The Coming of the American Behemoth (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2019).

[16] Nancy Fraser, “From Progressive Neoliberalism to Trump – and Beyond”, American Affairs,(Winter 2017 | Vol. I, No 4)Online at: https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2017/11/progressive-neoliberalism-trump-beyond/

I had to drive up to St. Francisville today, and on the way, continued listening to Jordan Peterson’s YouTube lecture on the book of Genesis. Peterson comes at the text not as a theologian, but as a psychologist. It’s a fascinating perspective. He believes that the great myths tell us something truthful about human nature, and about reality itself.

At some point, between errands, I stopped listening to Peterson and checked out the afternoon NPR newscast. I heard Rob Schmitz, who has been in New Zealand for a week covering the aftermath of the mosque shootings, talking about what he has seen and heard. I can’t find online a text of the back and forth between Schmitz and the “All Things Considered” anchor, but at some point, Schmitz was talking about visiting one morning a mosque that had not been attacked, and being met at the door by a man named Abdul who invited him in to have breakfast with the community.

Today, standing outside a mass funeral for many of the victims, Schmitz said he saw Abdul in the crowd. Abdul came over to him, gave him a big hug, and said, “I love you, brother.” Schmitz said he had succeeded all week in keeping his emotions in check while covering the story, but in that moment, he broke down.

It was an incredibly moving moment. I couldn’t help thinking of the Amish people who, back in 2006, embraced the grieving and humiliated mother of the deranged man who murdered five of their children before killing himself. How do people find it within themselves to do things like that? How do people find it in their hearts to say things like Farid Ahmad said? Excerpt:

A man whose wife was killed in the Christchurch mosque attack as she rushed back in to rescue him said he harbours no hatred towards the gunman, insisting forgiveness is the best path forward.

“I would say to him ‘I love him as a person’,” Mr Farid Ahmad told AFP.

Asked if he forgave the 28-year-old white supremacist suspect, he said: “Of course. The best thing is forgiveness, generosity, loving and caring, positivity.”

It is only by divine grace that they can. I would love to think that I could react the way those Christchurch Muslims, and the Amish from 2006, did if I suffered that kind of traumatic loss, but I know myself well enough to know that it would take everything I had simply to hold myself together and keep from falling to pieces. Offer someone else forgiveness? Tell a stranger I loved them? Embrace the humiliated and broken family of the man who murdered my child? It is very hard for me to make the leap of imagination necessary to do that. I hope that if, God forbid, I find myself in a situation like that, that I get out of my own way and let the grace of God work through me.

This terrorist sought to tear our nation apart with an evil ideology that has torn the world apart. But, instead, we have shown that New Zealand is unbreakable. And that the world can see in us an example of love and unity. We are broken-hearted but we are not broken. We are alive. We are together. We are determined to not let anyone divide us.

We are determined to love one another and to support each other. This evil ideology of white supremacy did not strike us first, yet it has struck us hardest. The number of people killed is not extraordinary but the solidarity in New Zealand is extraordinary.

To the families of the victims, your loved ones did not die in vain. Their blood has watered the seeds of hope. Through them, the world will see the beauty of Islam and the beauty of our unity. Do not say of those who have been killed in the way of Allah that they are dead. They are alive, rejoicing with their Lord.

I don’t believe that Islam is true, but I was thinking today, listening to Rob Schmitz’s account of being with the Islamic mourners, and that man Abdul who said, “I love you, brother,” that these people offer powerful witness to the Islamic faith. Islamic terrorists and others (e.g., Pakistani anti-Christian bigots) who do cruel and destructive things in the name of their faith obviously offer a terrible witness to Islam, but when you see religious believers doing something extraordinarily good in the name of faith, especially when every natural and reasonable impulse within you says not to do that thing — well, it’s a powerful thing. It could convert people.

I bring this all up in light of this passage from Jordan Peterson’s lecture, at the 1:06 point. Just click it; I have it cued to the precise moment. Watch it for at least three minutes:

What Peterson says, in a nutshell, is that we are all drawn to people who adopt a “mode of being” that gives them the power to live through catastrophes and affirm life anyway. We know that it could be otherwise, that we could choose to live in such a way that makes what is bad even worse. Those who choose the other path are people that we are drawn to from the depths of our being.

It sounds like a banal thing, but if you watch the entire lecture, it is really quite profound. Peterson connects this kind of response to suffering to the creation of the cosmos. He explains how, according to Genesis, God brought light to darkness, and ordered chaos. God used his power to bring harmony to that what was scattered. This, he says, is the power that we human beings have. We can choose to order, or we can choose to scatter. We can choose to live in harmony with each other, with the world, with being — or we can choose to live diabolically: to hurt, to scatter, to increase the world’s chaos and pain. This is an awesome responsibility, one that we cannot escape.

You know that famous line from one of Dostoevsky’s characters, the one you see on bumper stickers? It goes: Beauty will save the world. I was thinking not long ago, when I was visiting that Orthodox monastery in upstate New York, about that saying, and what it might mean. The poet and literary scholar James Matthew Wilson has some deep reflections on the meaning of beauty, thoughts I keep going back to again and again. I strongly recommend his book The Vision Of The Soul: Truth, Goodness, and Beauty In The Western Tradition. But tonight, I’m thinking of this post I put up in 2015 about some of his earlier writing and teaching about the nature of beauty. Here’s JMW:

A work of art’s integrity is its internal wholeness, and its proportion is its fitting relation to a potentially vast order of things part of and beyond itself. Clarity marks the proportion of a thing to our intellect, as Eco appreciates, but it also draws our intellect into luminous relation with the whole intelligible order of reality that proceeds from Beauty Itself. The work of art, in its beauty, therefore stands between the perceiving and the creative intellects, drawing the former toward the latter. We are oriented by beauty into the whole harmony of the cosmos; the individual artwork draws us toward a vision of the truth, goodness, and order of things.

More:

We can, after all, make an error in a math problem, but the judgment of the beautiful and the ugly can be instantaneous and irrevocable–even if it also develops and deepens gradually as the proportions of a thing unfold before our intellects. One can soften truth claims with qualifications and ethical judgments by couching them as kind reminders and positive enticements. But when a work of art is set before us to declare the lordship of God, as do, for instance, the churches of the high Middle Ages, there can be no such hesitation: as soon as we perceive a proportion as beautiful, it takes hold of us as much as we do of it.

Of course, the millions of tourists who visit Notre Dame or Chartres may beg to differ. They would tell us that they come for the beauty of the architecture, not for the Gospel in stone it claims to preach. But I can only reply, “It is the force of that Gospel already working within you. You cannot deny the presence of beauty; you sense its orderliness calling you to an order beyond itself but of which it is a part.”

Now, JMW is talking about works of art, not moral acts. In fact, JMW writes:

Aquinas appropriately emphasizes that beauty is distinct from goodness precisely because, where goodness leads us to the pleasure of possession, “beautiful things are those which please when seen.” The measurement of arithmetic concludes primarily in a true answer; but it and other measures may also be such that, when we see the way in which they fit together, we are pleased. Beauty’s root in the form is no understatement: we encounter beauty precisely when we see the form of a thing and how it fits within a larger harmony and order comprising other things. Beauty therefore designates an aspect of reality. It is ontological, and no less so because part of its reality may be its relation to the perception of a knowing subject.

Don’t you think, though, that witnessing from afar acts like those Muslims forgiving the killer, or showing love to strangers even amid their mourning, or the Amish doing what they did — don’t you think those profoundly moral acts also have about them an aesthetic quality, in that they draw us away from chaos and destruction, and towards the “larger harmony” of the God-created, God-saturated cosmos? When a human being performs an act that restores harmony and order and life to a reality that has been scattered and deadened by an act of evil, is this not a theophany, a revelation of the God who orders all things, and who declared his creation to be good?

The Muslim who publicly forgave his wife’s killer does not profess Jesus Christ, but that man is made in the image of God by virtue of his humanity, and, following Prof. Wilson, that Muslim man’s act stirred the force of the Gospel already working within me. I cannot deny the presence of beauty in what that Muslim man did — not just goodness, but beauty — and sense its orderliness calling me to an order beyond this bloody and cruel world. Here is the opening of the Gospel of John (verses 1-5), in David Bentley Hart’s gripping, idiosyncratic translation (He uses “GOD” where the original Greek uses “o theos,” referring to God in the fullest sense, and “god” where the Greek uses only “theos”.):

In the origin there was the Logos, and the Logos was present with GOD, and the Logos was god; This one was present with GOD in the origin. All things came to be through him, and without him came to be not a single thing that has come to be. In him was life, and this life was the light of men. And the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not conquer it.

As Hart writes in the essay accompanying his recent translation of the New Testament, the term “logos” has far more philosophical depth than the word we usually use in this passage, “Word”. It means “ordering principle,” “reason.” For Christians, it is God’s revelation of Himself active in creation. Jesus wasn’t just a symbol of the Logos; he was Logos, though also separate from God the Father. This all has to do with Trinitarian theology, and there’s no need to get into it here on this already too discursive blog post. My point is simply this: When people respond to catastrophic evil by showing love, in all its manifestations, the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness does not overcome it. They are meeting chaos with order, ugliness with beauty. Whether or not they know what they’re doing, they are revealing the Logos, who is Jesus Christ.

A Muslim (or a Buddhist, or any non-Christian) would of course disagree that his act of love reveals Jesus Christ, just as I would deny that the same act reveals Allah, or the Buddha-nature, or whatever. That’s fine — it’s an important argument, but not as important as the fact that for whatever reason, the chaos and darkness Brenton Tarrant brought into the world last week did not have the last word, and it did not have the last word because those Muslim people in Christchurch chose not to let it have the last word.

I’ve got to say, this is inspiring to me, and not just because it’s an example of what the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt calls “elevation”. I’ve been struggling with some difficult problems in my own life, though nothing remotely as difficult as what the survivors and mourners of Christchurch are dealing with. Still, it’s not nothing, and there are a lot of times when I wonder where God is in all this. Then I observe from afar acts of uncanny beauty and goodness amid immense pain and suffering, and I think, Oh, that’s right, He’s there. He’s here. There is meaning here, and that meaning is love, despite what it might seem like at the moment. Look, there it is, revealing itself in Christchurch, in the words and deeds of Muslim mourners.

This is how beauty will save the world.

Anyway, that’s what I’ve got for you tonight. May the memory of those killed in New Zealand be eternal. Those who mourn them are not Christians, but they have made the meaning of their city’s name — “Christchurch” — resonate powerfully, at least in the heart and the mind of this Christian. If there’s one thing that the Gospels tell us, it’s that God will manifest Himself where we least expect him to do so.

Inside story of how John Roberts negotiated to save Obamacare… (Third column, 10th story, link) Advertise here

INSTAGRAM to block anti-vaccine hashtags amid ‘misinformation’ crackdown… (Third column, 7th story, link) Related stories:Insurance Companies May Use Social MediaRead More

Special counsel Robert Mueller will not recommend any more indictments as part of his investigation, the Justice Department announced Friday evening.

Special counsel Robert Mueller on Friday delivered his report on possible collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia during theRead More

Erdogan urges fight on Islamophobia ‘like anti-Semitism after Holocaust’… (Third column, 11th story, link) Related stories:Muslim former detainee tells ofRead More

Muslim former detainee tells of China camp trauma… (Third column, 12th story, link) Related stories:Erdogan urges fight on Islamophobia ‘likeRead More

Dead man rides NYC subway during morning rush… (Third column, 9th story, link) Advertise here

Robert Mueller concluded the nearly two-year-long Russia investigation: He sent a final report chronicling his findings to Attorney General William Barr on Friday. Mueller and his team of investigators have unfurled threads of conspiracy by Russian nationals that have resulted in a number of indictments, though there are still a number of lingering questions that might fall to Congress to handle.

Michael Davidson, Norman Ornstein, and Thomas Mann—who were part of the commission that made the recommendations for rules around special-counsel investigations—write that the regulations were never intended to block Congress from ascertaining vital information. Ken Starr, who served as independent counsel during the Bill Clinton presidency, writes that the “solemn obligation is not to produce a public report,” and that Mueller “cannot seek an indictment. And he must remain quiet.”

+ Want to keep up with our Mueller coverage? Subscribe to our Politics & Policy Daily for the leading ideas and events in American politics.

The number of 2020 presidential hopefuls grows and grows. Joe Biden, the former vice president, looks to be careening toward a presidential run—as does Senator Michael Bennet of Colorado, a moderate with business experience who is branding himself as a someone who knows how to work with Republicans. With still nearly a year before the first votes are cast, political commentators are hyper-focused on one dynamic in particular: electability. But Peter Beinart argues that all this chatter about whether a certain candidate is electable is based on dubious assumptions and polls that are too early to matter. A better strategy would focus on what candidates would do if they won.

? Of the 895 current eighth graders who secured a spot this coming year at Stuyvesant—one of several of New York City’s test-in public high schools—just seven identify as African American. But black enrollment at Stuyvesant has rapidly declined every year since its peak more than four decades ago: The school enrolled how many black students out of 2,536 total in 1975?

⚾ This week saw the largest deal in the history of American sports: How many million for a 12-year contract for the center-fielder Mike Trout of the Los Angeles Angels? (The question isn’t whether Trout should earn that salary, argues Robert O’Connell. It’s whether the Angels deserve to be the team paying it.)

? The amount of electronic waste Americans generate is up at least 80 percent from 2000, reaching about how many million tons of e-waste in 2012? (Just 29 percent of that is recycled, and fancy device makers such as Apple aren’t exactly incentivized to push out fewer new products.)

(Universal)

Watch: Jordan Peele’s complex new film, Us. Unsure of whether you can stomach the horror genre? Us is also an “ambitious sci-fi allegory and a pitch-black comedy of the haves and have-nots,” David Sims writes.

Listen: As you wait for HBO’s Game of Thrones to return for its final season next month, revisit the composer Ramin Djawadi’s score for the show. Spencer Kornhaber visited Djawadi in his studio to lift the curtain on his musical process.

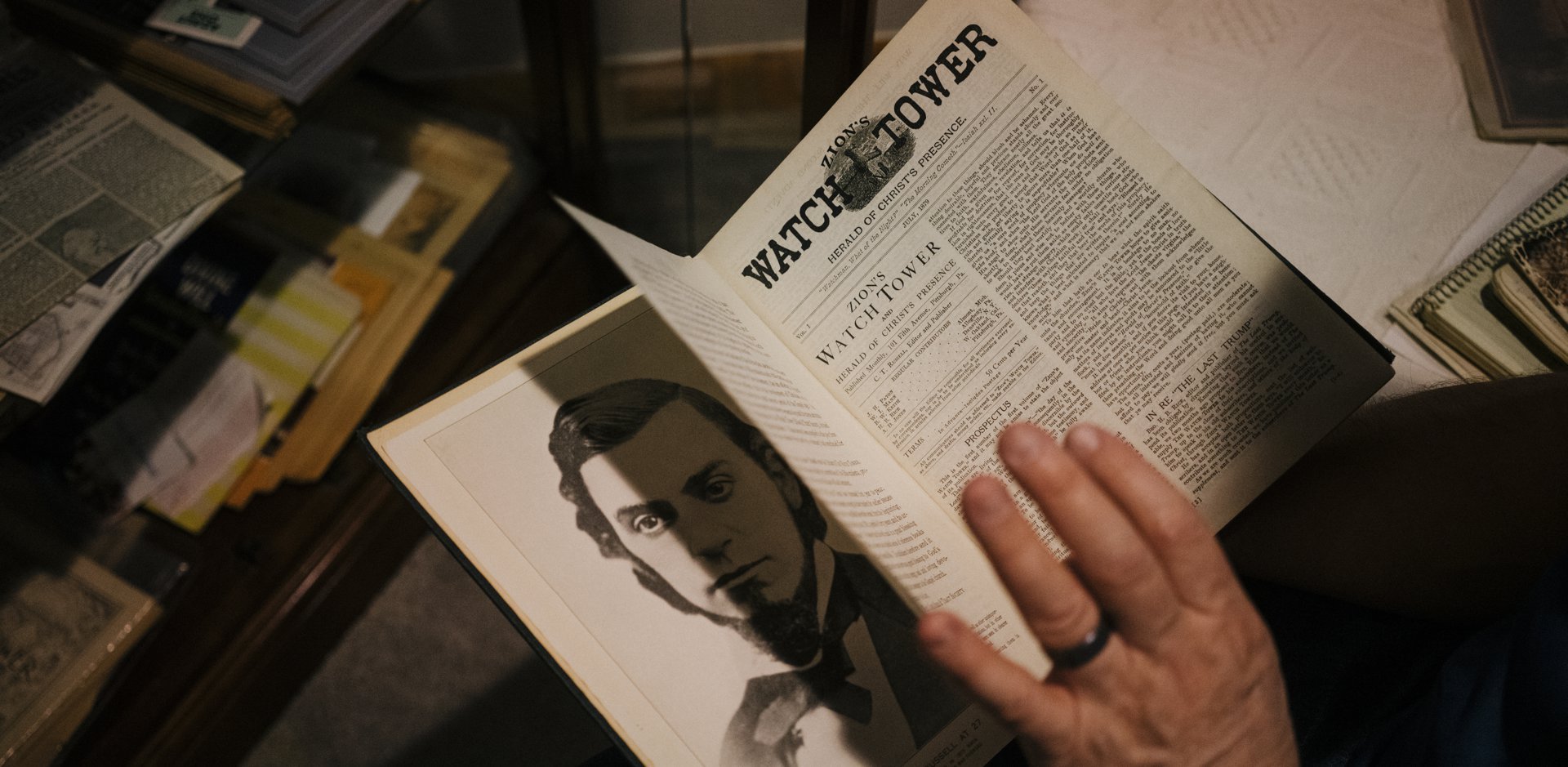

A former Jehovah’s Witness is using stolen documents to expose allegations that the religion has kept hidden for decades.

In March 1997, the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, the nonprofit organization that oversees the Jehovah’s Witnesses, sent a letter to each of its 10,883 U.S. congregations, and to many more congregations worldwide. The organization was concerned about the legal risk posed by possible child molesters within its ranks. The letter laid out instructions on how to deal with a known predator: Write a detailed report answering 12 questions—Was this a onetime occurrence, or did the accused have a history of child molestation? How is the accused viewed within the community? Does anyone else know about the abuse?—and mail it to Watchtower’s headquarters in a special blue envelope. Keep a copy of the report in your congregation’s confidential file, the instructions continued, and do not share it with anyone.

Thus did the Jehovah’s Witnesses build what might be the world’s largest database of undocumented child molesters.

(Audrey McAvoy / AP / The Atlantic)

The celebrated American poet and translator W. S. Merwin, who died last week at his home in Maui, Hawaii, at 91, was for many years an abiding and stirring presence in The Atlantic’s pages. There is much to surface, including one of The Atlantic’s rare commissioned poems, Merwin’s translation of the closing canto of Dante’s Paradiso. If few poets were so prolific, fewer still were as resolute in their restless lyric energy. The constellation of Merwin poems in the Atlantic archives attests to the fluent range of his singular sound and sense, confirming at every turn the longtime poetry editor Peter Davison’s view that “the intentions of Merwin’s poetry are as broad as the biosphere yet as intimate as a whisper.”

Merwin’s writing was weighted with melancholy expectations of a premature ending. In 1999’s “Term,” Merwin writes another ending to the search for just the right word: “who would ever have thought it was the one / saying itself from the beginning through / all its uses and circumstances to / utter at last that meaning of its own.” Again and again, his speakers seek an elusive revelation, only to find that what they sought was present all along. In a sense, the familiarity of these endings renders futile all the searching and waiting that Merwin describes. But the ending also redeems the empty steps that came before it.

— Annika Neklason, archives editor

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here.

Comments, questions, typos? Email newsletters editor Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com

We have many other free email newsletters on a variety of other topics. Find the full list here.

President TrumpDonald John TrumpJoint Chiefs chairman denies report that US is planning to keep 1K troops in Syria Kansas Department of Transportation calls Trump ‘delusional communist’ on Twitter Trump has privately voiced skepticism about driverless cars: report MORE on Monday called Joe BidenJoseph (Joe) Robinette BidenBeto could give Biden and Bernie a run for their money Biden: ‘I have the most progressive record of anybody running … anybody who would run’ H.R. 1 falls short of real reform MORE a “low I.Q. individual” after the former vice president had a slip of the tongue and nearly announced he was running for president in 2020.

“Joe Biden got tongue tied over the weekend when he was unable to properly deliver a very simple line about his decision to run for President,” Trump tweeted. “Get used to it, another low I.Q. individual!”

Joe Biden got tongue tied over the weekend when he was unable to properly deliver a very simple line about his decision to run for President. Get used to it, another low I.Q. individual!

Trump has previously deployed the “low I.Q.” line of attack against a number of critics, including MSNBC host Mike Brzezinski, Rep. Maxine WatersMaxine Moore WatersOn The Money: Senate rejects border declaration in rebuke to Trump | Dems press Mnuchin on Trump tax returns | Waters says Wells Fargo should fire its CEO Maxine Waters says Wells Fargo should fire its CEO On The Money: Wells Fargo chief gets grilling | GOP, Pence discuss plan to defeat Dem emergency resolution | House chair sees ’50-50′ chance of passing Dem budget | Trump faces pressure over Boeing MORE (D-Calif.) and actor Robert De Niro.

The president was seizing on a mishap from Biden over the weekend where he told a gathering of Delaware Democrats that he has “the most progressive record of anybody running for the … anybody who would run” for the 2020 nomination.

Attendees began applauding as Biden repeated the phrase, “Of anybody who would run.”

Biden has long been mulling a presidential campaign for 2020 and is considered a near certainty to jump in the race.

The former vice president has been an ardent critic of the president and caused a stir last year when he said he would have “beat the hell out of” Trump in high school over his degrading comments about women.

Biden has typically hovered at or near the top of polling among Democrats on their preferred 2020 candidate.

A poll released earlier this month showed Biden was the top choice among likely Iowa Democratic caucus participants, garnering 27 percent of the vote. Sen. Bernie SandersBernard (Bernie) SandersO’Rourke faces pressure from left on ‘Medicare for all’ O’Rourke says he won’t use ‘f-word’ on campaign trail O’Rourke not planning, but not ruling out big fundraisers MORE (I-Vt.) was the first choice of 25 percent of those surveyed.

Should Biden officially announce his candidacy, he would join an increasingly crowded field of presidential hopefuls.

Beto O’RourkeRobert (Beto) Francis O’RourkeO’Rourke faces pressure from left on ‘Medicare for all’ O’Rourke says voters aren’t interested in ‘personal attacks’ like GOP tweet O’Rourke says he won’t use ‘f-word’ on campaign trail MORE, the former Texas congressman, entered the race last week, joining Sanders, Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), Kamala Harris (D-Calif.), Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) and Cory Booker, among others.

Trump has previously welcomed the idea of facing off against the former vice president, calling him a “dream opponent.”

Last week, he declined to say whether he viewed Biden or O’Rourke as a stronger challenger, telling reporters “Whoever it is, I’ll take him or her on.”

Updated at 9:46 a.m.

Congressional Democrats are demanding immediate access to Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report, now in the hands of Attorney General William Barr.

“Congress and the American people deserve to judge the facts of the Mueller report for themselves,” Democratic Sen. Mark Warner, vice chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, said in a statement on Twitter. “It must be provided to Congress immediately, and the AG should swiftly prepare a declassified version for the public”

“Nothing short of that will suffice,” he added.

The report covering the nearly two-year investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election was sent to the Justice Department Friday afternoon, and Barr can now decide what parts to release to Congress and the public. In a letter to Congress Friday afternoon, the attorney general said that might provide the “principal conclusions as soon as this weekend.”

But Democratic leaders, particularly those running for president, want to see the full scope of the report now, including the underlying facts that Mueller determined did not warrant indictments.

READ: Everything we already know about the Mueller investigation

“Americans deserve to know the truth now that the Mueller report is complete,” Sen. Kamala Harris, a 2020 candidate for president, wrote in a tweet. “The report must be released immediately, and AG Barr must publicly testify under oath about the investigation’s findings. We need total transparency here.”

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer said in a joint statement that Trump’s staff shouldn’t get a “sneak preview.”

“The American people have a right to truth,” they wrote. “The watchword is transparency.”

Democratic candidate for president and former Congressman Beto O’Rourke added: “Release the Mueller report to the American people.”

The White House said it has not yet seen the document.

Republicans weighed in, too. Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina tweeted that he’ll work with Congress to “ensure as much transparency as possible, consistent with the law.” (He blocked the Senate from voting on a bipartisan resolution to make the report public.)

Earlier this week, President Donald Trump said he’d be fine with the American public seeing the report after bashing Mueller and his probe for months. Donald Trump, Jr., the president’s son, meanwhile, simply tweeted “#CollusionTruthers” after the report dropped.

Other Republicans, such as Rep. Doug Collins of Georgia, wrote on Twitter that they look forward to reviewing the report and making their determinations after.

Sen. Richard Burr, a Republican from North Carolina, said he trusts Mueller did a fair job with his findings.

“After 2 years, the special counsel has concluded his investigation, & I look forward to reviewing AG Barr’s report carefully, when it becomes available. I expect DOJ to release the special counsel’s report to this committee & public w/o delay & to maximum extent permitted by law,” Collins tweeted.

Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley, the prolific tweeter from Iowa and user of sometimes confusing shorthand, tweeted: “PTL the Mueller investigation is over Waiting w breathless anticipation of what it says.”

Cover image: U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, a Democrat from California, speaks during a luncheon event at the Economic Club of Washington D.C. in Washington, D.C., U.S., on Friday, March 8, 2019. (Photo: Alex Edelman/Bloomberg via Getty Images)