EXCLUSIVE: Leaked Messages Show Google Employees Freaking Out Over Heritage Foundation Link

Google employees smear the Heritage Foundation’s president as a “vocal bigot,” “transphobe,” and “exterminationist.”

Elon Musk’s Shadowy Alliance with Vladimir Putin: A National Security Threat

Elon Musk’s Shadowy Alliance with Vladimir Putin: A National Security Threat  The Unconventional Diplomatic Dynamics Shaping Global Relations: Trump, Musk, and Covert Negotiations

The Unconventional Diplomatic Dynamics Shaping Global Relations: Trump, Musk, and Covert Negotiations  Ethicoin’s Role in Shaping the Future of the Federal Reserve System’s U.S. Central Bank Digital Currency

Ethicoin’s Role in Shaping the Future of the Federal Reserve System’s U.S. Central Bank Digital Currency  Record Volumes of Russian LNG Replace Pipeline Gas in Europe

Record Volumes of Russian LNG Replace Pipeline Gas in Europe The Los Angeles Dodgers are suing a toy company for failing to manufacture 42,000 Tommy Lasorda bobblehead dolls, that wereRead More

The home of music producer Mally Mall was raided by federal officials alleging he is involved in sexual assault andRead More

Sharia law plunges Brunei gay community into fear… (Third column, 16th story, link) Advertise here

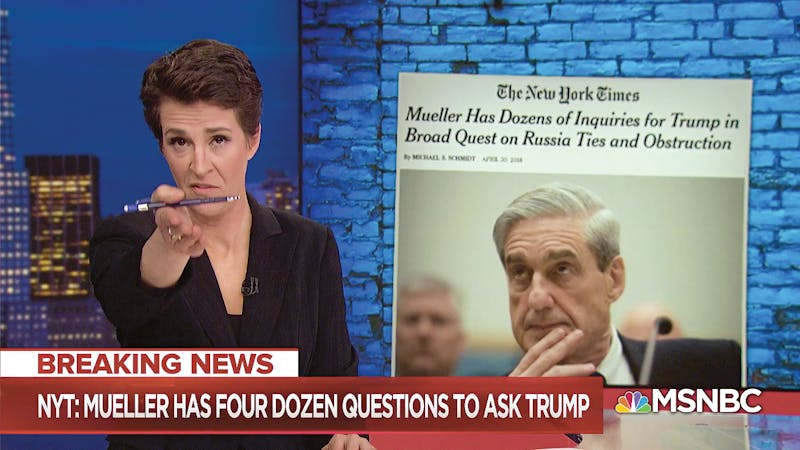

On January 31, Rachel Maddow, the eponymous host of The Rachel Maddow Show, returned from a commercial break. In the previous segment, she had interviewed Betsy Woodruff, a Daily Beast reporter, who had written a story on alleged connections between the Russian government and the National Rifle Association. Before that, Maddow had conducted a friendly and knowing colloquy with Adam Schiff, the newly seated Democratic chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, on his expansive plans to delve into the sprawling Russia investigation.

“Today,” she said as she came back on screen, “some new bread crumbs were dropped in the mystery case that has been winding its way through the federal courts in D.C. since last August.”

“Bread crumbs” are emblematic of the informal house style at MSNBC. The channel has a range of on-air talent, and its shows each have their own cadence and feel, but they are joined across the arc of each daylong cycle of programming, and especially the larger meta-cycle of the Russia investigation, by a kind of Sherlockian, my-dear-Watson zeal. We are discovering the clues, uncovering the documents, connecting the threads, following the trail in the forest.

A mystery is a puzzle to solve, but a conspiracy can only produce more and more mysteries. What did we find, for example, at the end of the trail of bread crumbs on January 31? “It’s a case,” Maddow said:

… that is very intriguing, in part because of what we don’t know about it. We know it involves Robert Mueller and the special counsel. We know it’s being handled with alacrity in the federal court system. But we otherwise don’t know what it’s about. It involves a corporation. We don’t know which one. A corporation that is wholly owned by a foreign country. We don’t know what country. It appears this mystery corporation has been fighting a subpoena from Mueller. And we think we know now that a federal judge is fining this corporation $50,000 a day for every day that they refuse to comply with that Mueller subpoena. Well, late last night, we got a few more bread crumbs in this case when the court unsealed a redacted version of the docket for this case.

It may well have been that this case involved a witness in Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation of matters related to Russian interference in the 2016 elections. Beyond that? “It could be anyone who’s been subpoenaed by the special counsel for anything,” an anonymous attorney representing a Trump staffer told Politico.

var tns=function(){var t=window,Oi=t.requestAnimationFrame||t.webkitRequestAnimationFrame||t.mozRequestAnimationFrame||t.msRequestAnimationFrame||function(t)return setTimeout(t,16),e=window,Di=e.cancelAnimationFrame||e.mozCancelAnimationFrame||function(t)clearTimeout(t);function Hi(),a=1,r=arguments.length;a<r;a++)if(null!==(t=arguments[a]))for(e in t)i!==(n=t[e])&&void 0!==n&&(i[e]=n);return ifunction ki(t)return 0<=["true","false"].indexOf(t)?JSON.parse(t):tfunction Ri(t,e,n,i)if(i)tryt.setItem(e,n)catch(t)return nfunction Ii()((e=t.createElement("body")).fake=!0),evar n=document.documentElement;function Pi(t)var e="";return t.fake&&(e=n.style.overflow,t.style.background="",t.style.overflow=n.style.overflow="hidden",n.appendChild(t)),efunction zi(t,e)t.fake&&(t.remove(),n.style.overflow=e,n.offsetHeight)function Wi(t,e,n,i)"insertRule"in t?t.insertRule(e+""+n+"",i):t.addRule(e,n,i)function Fi(t)return("insertRule"in t?t.cssRules:t.rules).lengthfunction qi(t,e,n)for(var i=0,a=t.length;i<a;i++)e.call(n,t[i],i)var i="classList"in document.createElement("_"),ji=i?function(t,e)return t.classList.contains(e):function(t,e)return 0<=t.className.indexOf(e),Vi=i?function(t,e)t.classList.add(e):function(t,e)(t.className+=" "+e),Gi=i?function(t,e)ji(t,e)&&t.classList.remove(e):function(t,e)ji(t,e)&&(t.className=t.className.replace(e,""));function Qi(t,e)return t.hasAttribute(e)function Xi(t,e)return t.getAttribute(e)function r(t)return void 0!==t.itemfunction Yi(t,e)function Ki(t,e)t=r(t)function Ji(t)for(var e=[],n=0,i=t.length;n<i;n++)e.push(t[n]);return efunction Ui(t,e)"none"!==t.style.display&&(t.style.display="none")function _i(t,e)"none"===t.style.display&&(t.style.display="")function Zi(t)return"none"!==window.getComputedStyle(t).displayfunction $i(e)if("string"==typeof e)var n=[e],i=e.charAt(0).toUpperCase()+e.substr(1);["Webkit","Moz","ms","O"].forEach(function(t)n.push(t+i)),e=nfor(var t=document.createElement("fakeelement"),a=(e.length,0);a<e.length;a++)var r=e[a];if(void 0!==t.style[r])return rreturn!1function ta(t,e)var n=!1;return/^Webkit/.test(t)?n="webkit"+e+"End":/^O/.test(t)?n="o"+e+"End":t&&(n=e.toLowerCase()+"end"),nvar a=!1;tryvar o=Object.defineProperty(,"passive",get:function()a=!0);window.addEventListener("test",null,o)catch(t)var u=!!a&&passive:!0;function ea(t,e,n)for(var i in e)var a=0<=["touchstart","touchmove"].indexOf(i)&&!n&&u;t.addEventListener(i,e[i],a)function na(t,e)for(var n in e)var i=0<=["touchstart","touchmove"].indexOf(n)&&u;t.removeEventListener(n,e[n],i)function ia()returntopics:,on:function(t,e)[],this.topics[t].push(e),off:function(t,e)if(this.topics[t])for(var n=0;n<this.topics[t].length;n++)if(this.topics[t][n]===e)this.topics[t].splice(n,1);break,emit:function(e,n)n.type=e,this.topics[e]&&this.topics[e].forEach(function(t)t(n,e))Object.keys||(Object.keys=function(t)var e=[];for(var n in t)Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty.call(t,n)&&e.push(n);return e),"remove"in Element.prototype||(Element.prototype.remove=function()this.parentNode&&this.parentNode.removeChild(this));var aa=function(O){O=Hi(container:".slider",mode:"carousel",axis:"horizontal",items:1,gutter:0,edgePadding:0,fixedWidth:!1,autoWidth:!1,viewportMax:!1,slideBy:1,center:!1,controls:!0,controlsPosition:"top",controlsText:["prev","next"],controlsContainer:!1,prevButton:!1,nextButton:!1,nav:!0,navPosition:"top",navContainer:!1,navAsThumbnails:!1,arrowKeys:!1,speed:300,autoplay:!1,autoplayPosition:"top",autoplayTimeout:5e3,autoplayDirection:"forward",autoplayText:["start","stop"],autoplayHoverPause:!1,autoplayButton:!1,autoplayButtonOutput:!0,autoplayResetOnVisibility:!0,animateIn:"tns-fadeIn",animateOut:"tns-fadeOut",animateNormal:"tns-normal",animateDelay:!1,loop:!0,rewind:!1,autoHeight:!1,responsive:!1,lazyload:!1,lazyloadSelector:".tns-lazy-img",touch:!0,mouseDrag:!1,swipeAngle:15,nested:!1,preventActionWhenRunning:!1,preventScrollOnTouch:!1,freezable:!0,onInit:!1,useLocalStorage:!0,O||);var D=document,h=window,a=ENTER:13,SPACE:32,LEFT:37,RIGHT:39,e=,n=O.useLocalStorage;if(n)var t=navigator.userAgent,i=new Date;try(e=)catch(t)n=!1n&&(e.tnsApp&&e.tnsApp!==t&&["tC","tPL","tMQ","tTf","t3D","tTDu","tTDe","tADu","tADe","tTE","tAE"].forEach(function(t)e.removeItem(t)),localStorage.tnsApp=t)var r,o,u,l,s,c,f,y=e.tC?ki(e.tC):Ri(e,"tC",function()var t=document,e=Ii(),n=Pi(e),i=t.createElement("div"),a=!1;e.appendChild(i);tryfor(var r,o="(10px * 10)",u=["calc"+o,"-moz-calc"+o,"-webkit-calc"+o],l=0;l<3;l++)if(r=u[l],i.style.width=r,100===i.offsetWidth)a=r.replace(o,"");breakcatch(t)return e.fake?zi(e,n):i.remove(),a(),n),g=e.tPL?ki(e.tPL):Ri(e,"tPL",function()var t,e=document,n=Ii(),i=Pi(n),a=e.createElement("div"),r=e.createElement("div"),o="";a.className="tns-t-subp2",r.className="tns-t-ct";for(var u=0;u<70;u++)o+="

“;return r.innerHTML=o,a.appendChild(r),n.appendChild(a),t=Math.abs(a.getBoundingClientRect().left-r.children[67].getBoundingClientRect().left)<2,n.fake?zi(n,i):a.remove(),t(),n),H=e.tMQ?ki(e.tMQ):Ri(e,"tMQ",(o=document,u=Ii(),l=Pi(u),s=o.createElement("div"),c=o.createElement("style"),f="@media all and (min-width:1px).tns-mq-testposition:absolute",c.type="text/css",s.className="tns-mq-test",u.appendChild(c),u.appendChild(s),c.styleSheet?c.styleSheet.cssText=f:c.appendChild(o.createTextNode(f)),r=window.getComputedStyle?window.getComputedStyle(s).position:s.currentStyle.position,u.fake?zi(u,l):s.remove(),"absolute"===r),n),d=e.tTf?ki(e.tTf):Ri(e,"tTf",$i("transform"),n),v=e.t3D?ki(e.t3D):Ri(e,"t3D",function(t)if(!t)return!1;if(!window.getComputedStyle)return!1;var e,n=document,i=Ii(),a=Pi(i),r=n.createElement("p"),o=9<t.length?"-"+t.slice(0,-9).toLowerCase()+"-":"";return o+="transform",i.insertBefore(r,null),r.style[t]="translate3d(1px,1px,1px)",e=window.getComputedStyle(r).getPropertyValue(o),i.fake?zi(i,a):r.remove(),void 0!==e&&0<e.length&&"none"!==e(d),n),x=e.tTDu?ki(e.tTDu):Ri(e,"tTDu",$i("transitionDuration"),n),p=e.tTDe?ki(e.tTDe):Ri(e,"tTDe",$i("transitionDelay"),n),b=e.tADu?ki(e.tADu):Ri(e,"tADu",$i("animationDuration"),n),m=e.tADe?ki(e.tADe):Ri(e,"tADe",$i("animationDelay"),n),C=e.tTE?ki(e.tTE):Ri(e,"tTE",ta(x,"Transition"),n),w=e.tAE?ki(e.tAE):Ri(e,"tAE",ta(b,"Animation"),n),M=h.console&&"function"==typeof h.console.warn,T=["container","controlsContainer","prevButton","nextButton","navContainer","autoplayButton"],E=;if(T.forEach(function(t)if("string"==typeof O[t])!n.nodeName)return void(M&&console.warn("Can't find",O[t]));O[t]=n),!(O.container.children.length<1))();

var slider = tns(

container: '.bacharach-slider',

nav: false,

controls: false,

swipeAngle: false,

fixedWidth: 120,

edgePadding: 5,

loop: false,

responsive:

615:

disable: true

);

var selections = document.querySelectorAll('.portrait, .bacharach-portait-info');

for (var i = 0; i < selections.length; i++)

selections[i].addEventListener('mouseup', function()

clickHandler(this);

, false);

function clickHandler(t)

clearSelection();

var index = indexInParent(t);

if (document.querySelector(".tns-slider"))

slider.goTo(index-1);

const nodeList = document.querySelectorAll(".p-"+index);

for (var i = 0; i < nodeList.length; i++)

nodeList[i].classList.add('selected');

document.querySelector('.portrait-timeline').id = "p-"+index;

if (index == 3)

document.querySelector('.portrait-timeline.b#p-3').classList.add('ready');

else

document.querySelector('.portrait-timeline.b#p-3').classList.remove('ready');

function clearSelection()

for (var i = 0; i < selections.length; i++)

selections[i].classList.remove('selected');

function indexInParent(node)

var children = node.parentNode.childNodes;

var num = 1;

for (var i=0; i<children.length; i++)

if (children[i]==node) return num;

if (children[i].nodeType==1) num++;

return -1;

console.log('slider init');

The prevailing criticism of Maddow’s on-air personality is that she embodies the stereotype of the smug liberal, and if you encounter her mainly through the brief video clips that are both the reputational currency and the lingua franca of online media, it’s easy to see why. She has a bit of a shtick—a habit of cocking her head or raising her eyebrow and speaking confidently but with an air of almost bemused incredulity. Can you, she seems to be asking, believe these guys? She gestures widely. She shrugs. She is arch and broadly ironic. She is very certain that she is right.

But when I set myself the task of really watching her show, beginning to end, and for more than one night in a row, I discovered that she was far more appealing than I’d been prepared to find her. Her voice is low and a bit sinusy; it has more in common with the worlds of stand-up, DIY podcasting, or public-radio storytelling than with the prosecutorial sharpness of a lot of cable news. Maddow is sincere without being overly earnest. She thinks that she is funnier than she is, but we all have friends who think they are funnier than they are. She is obviously smart, which makes the frequent weirdness and obscurantism of her show seem like a deliberate choice, like a serious author who has, for fun, decided to dabble in the absurd.

She has learned the art of looking into the camera while speaking to the guy behind it. It gives the sense that she just found herself sitting there, having this conversation with her producers and her crew, and this gives her show an immediacy and intimacy. We know that the case is “being handled with alacrity.” We know about this “federal judge’s” fines against this mysterious company. We are in on it.

Immediacy and intimacy are necessary for a show that consists, for long stretches, of a basically inert shot of a single woman who occupies the left-hand two-thirds of your screen, talking. But these qualities also render less conspicuous the defining trait of the show, which more than any other has contributed to Mueller’s near-messianic hold over segments of the so-called Resistance—a movement that was caught by surprise when Mueller finally submitted his report in late March, apparently concluding, from what we know of the report as of this writing, that Trump and his aides had not conspired with Russia to steal the election. Maddow’s prime-time hour of overheated speculation lacks the antic sensibility and maudlin sentimentality of, for instance, the pre-exile Glenn Beck, who had scribbled all his manic and intricate chalkboard theories of history as conspiracy (and vice versa) with the studied passion of a coffee-shop prophet. But Maddow—and much of her network these days—is frequently just as bonkers.

MSNBC has had up-and-down ratings over the years, but a sharp downturn toward the end of the Obama presidency pushed the network nearly to also-ran status. By 2015, its popularity sometimes dipped below not just Fox News and CNN, but also CNN’s airport-lounge spin-off, HLN. There was speculation that it had become too liberal, that the appetite for stem-winding perorations in the vein of Keith Olbermann’s raucous, Bush-era “special comment” programming was simply too limited, and that there was perhaps no national market for a left-leaning counterpart to Fox.

Then came the 2016 elections, and the incredible rise and victory of Donald Trump. Leslie Moonves, the erstwhile chairman of CBS, infamously claimed that Trump’s entry into politics “may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS.” That despairing formulation has proved doubly true for MSNBC. By late 2018, MSNBC could, on certain weeks, claim to be the number one news network on cable. Its relentless focus on the minutiae of Trump world scandals—which Trump world obligingly delivers in endless variety and quantity—and its impressive ability to turn late-breaking, mad-making Trump pronouncements into a whole evening of dedicated programming, are especially well adapted to a political moment driven by the wickedly fast churn of online media. MSNBC has become what, just a few years ago, critics thought impossible: the liberal, Democratic cable channel. It is the touchstone network for the Resistance movement on social media, which is itself tightly wound around allegations of Russian plots and “collusion,” and its stars look likely to become kingmakers in the coming Democratic primaries. Since the New Year and as of this writing, Senators Kirsten Gillibrand, Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren, Cory Booker, and Amy Klobuchar, all announced presidential candidates, have made appearances on The Rachel Maddow Show.

The network has, in other words, quickly settled into a winning formula, and the effect of spending a whole evening with MSNBC for the first time is not unlike wandering into a scripted prestige television series in the middle of its third season. The careful place setting occurred long before you started watching, and now the narrative is barreling ahead.

There is the big, established cast of principal characters. Chris Hayes, whose mouth pinches and eyes widen behind his plastic frames as he struggles not to interject “correct” over whatever his friendly guest is already saying. Chris Matthews, whose interruptions are more staccato and reflexive, like a person who has done uppers and can’t let a single song play to its end without changing the record. Ari Melber: lawyerly, handsome, young but not quite as young as he wants to appear, reminding you that he listens to hip-hop. Maddow: extemporaneous, soliloquizing. Lawrence O’Donnell: calmer than the posturing 2010 character who got himself kicked off Morning Joe for his prosecutorial (and, frankly, correct) denunciation of former Bush speechwriter Marc Thiessen and the whole Bush administration for falling down on the job before 9/11, but still evincing a West Wing style of righteous, lettered indignation—appropriate, since he was a writer and producer on the show that, perhaps more than any other cultural artifact, shaped the sensibility of post-Bush liberalism, including that of MSNBC.

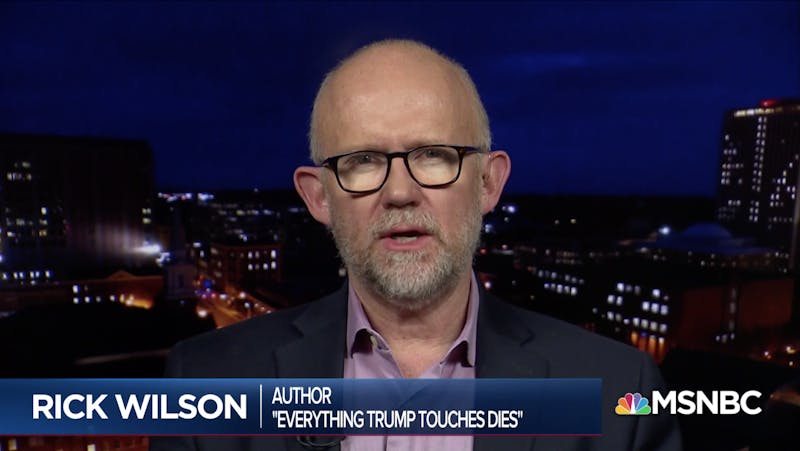

There are the guests: a square-headed John Brennan, “former director of the CIA.” Rick Wilson, “the Republican strategist” who despises Trump. The “former federal prosecutor.” Print journalists who just happen to be conventionally attractive. Low-ranking Democratic House members. There is Trump himself, looming offstage, the oddly absent centerpiece of the whole production, like Julius Caesar in the later acts of Shakespeare’s play. There is Mueller, something between an oracle and a demiurge, also physically absent, and there was Mueller’s report, a promised deus ex machina hanging in the fly space above. There are Michael Cohen, Roger Stone, and a Russian oligarch whose name everyone pronounces differently.

There are set-piece locations: Trump Tower, the site of a 2016 meeting between Donald Trump Jr. and Kremlin agents that became central to the Russia investigation; a Moscow hotel; “the Border”; the White House. There is a complex establishing mythology, a series of actual acts and hypothetical acts and possibly mythological acts that, in total, build the texture of a sprawling world. There are terms of art and law that everyone seems to understand; they take the place, in this universe, of a fantasy show’s invented ancient language.

It has, in other words, the strange simultaneity common to prestige TV: It is at once vast and circumscribed. A wider world intrudes, but the same central heroes and villains show up, week after week.

MSNBC is conventionally assumed to be the liberal network in the sense that Fox News is conservative, although MSNBC has been through several iterations since its founding in 1996. Its earlier years were a wild grab bag of discordant content. Imus in the Morning, featuring shock jock Don Imus, ran for years in the long morning block that would eventually be colonized by the flirtatious coffee klatch of Morning Joe. There was The Site, a technology-focused hour anchored by Soledad O’Brien and … a computer-generated hipster with an earring and pink hair named Dev Null. (It did not last long.) There was a two-hour block of Mitch Albom, who wrote the bestselling books about the people you meet in heaven.

From the late 1990s through the mid-2000s, the network also served as a weird clearinghouse for some of the great ghouls of conservative agit-prop, an early home-away-from-home for the likes of Laura Ingraham, Ann Coulter, and Tucker Carlson, though the latter was still in his clubby William F. Buckley phase and not yet banging on about racial destiny and birth rates. It hired Michael Savage, a virulent radio hate jock, but had to fire him a few months later when he screamed at a call-in listener, “You should only get AIDS and die, you pig!” Does anyone remember Alan Keyes Is Making Sense? If not, you may instead recall the omnipresence of Pat Buchanan.

This succession of short-lived programs seems to have been the product of a network struggling and failing to capture the political zeitgeist at the end of the millennium, as the Clinton era bled into the strange, bloody reaction of the Bush years. But as the Bush administration wore on, MSNBC began its turn toward liberalism, foregrounding anti-Bush voices like Olbermann and eventually hiring Maddow.

But MSNBC’s brand of liberalism, as well as the general sense that it is effectively a partisan Democratic outfit, are a fascinating product of an ideological incubation that occurred during the Obama years, which marked an inflection point in what will, I suspect, be seen by historians not just as a hardening of partisan sorting and polarization of the electorate, but as part of a much larger ideological realignment.

These changes had been going on since the days of Reagan at least, but in the calm, technocratic, white-collar, highly professional person of Barack Obama and the party he remade in his image, they came to a head. Through the conservative uproar that met this racial and cultural interloper, via the increasingly intransigent and combative Republican Congress, and the vitriolic outpourings of the Tea Party, conservative talk radio, and the Murdoch empire, something new emerged clearly for the first time. Suddenly, the Republicans were the wild reformists, coming with axes and dynamite for all the edifices of society and government that America had erected over the last 100 years, while the Democratic Party was the conservative party, which is to say: protective toward institutions, deferential toward established power, defensive around precedent, and deeply concerned that anything other than narrow tinkering at the margins represented a dangerous radicalism.

Somewhat ironically, the failures of establishment institutions were the central theme of Chris Hayes’s 2012 book, Twilight of the Elites: America After Meritocracy. Hayes is relatively unsparing in his assessments of elite failures, from the collapse of Enron to the financial crisis. But the book suffers throughout from a habit of dividing phenomena into catchy but facile dichotomies. In Twilight of the Elites, these are Burkean “institutionalists” and more radical “insurrectionists.” Hayes confesses his own sentiments early on:

Whatever my own insurrectionist sympathies—and they are considerable—I am also stalked by the fear that the status quo, in which discredited elites and institutions retain their power, can just as easily produce destructive and antisocial impulses as it can spur transformation and reform. Call it my inner David Brooks.

This fear is not unfounded. “Destructive and antisocial” as a description of Donald Trump and the GOP in 2019 reads as restrained to the point of parody. But the conservative abhorrence of any revolution that exceeds the mandate of mere reform is inadequate to the problems that Hayes himself diagnoses. It leads directly to a central problem with contemporary mainstream liberalism: the idea that the trouble is not so much institutions themselves as the people who run them. The result is an unfortunate tendency to rehabilitate dubious people and organizations the moment they line up against the right villains. How else to explain the sudden liberal affection for the FBI, the office of the special counsel, the “intelligence community”?

Today, MSNBC’s liberalism and partisanship can only be understood in this framework. The presidency of Donald Trump is, in this analysis, more than anything else an affront to institutions and traditions. The network is far more equipped to deal with these affronts than the political and policy content of his administration.

On a recent episode of The Beat With Ari Melber, for example, it took a calm but clearly exasperated Katrina vanden Heuvel, publisher of the left-leaning The Nation, to point out that Trump’s rhetorical hostility to open-ended military conflicts and occupations represented an actual opportunity to begin a conversation about American military de-escalation rather than to natter on, again, about the irresponsibility of yanking troops out of Syria, however crass and inconsistent his reasoning—such as it is—might be.

Moments like this are few, in large part because the network so rarely finds time to pan out from its narrow focus on the baroque divagations of the investigations of Donald Trump, his political and business associates, and the specter of Russian interference in our elections.

Prominent critics of MSNBC and the Russiagate-media complex, such as The Intercept’s Glenn Greenwald, have complained about the willingness of American journalists to chase any Russki rabbit down a Red Scare hole. I have been a skeptic of any overarching Russian state conspiracy, but I think it requires a contrarianism bordering on deliberate naïveté to insist there is nothing to it at all. The Mueller investigation is now complete, although it is not yet public as of this writing, and it is a little silly to say that the last two years have produced only sound and fury. People have gone to jail, and it seems plain that other legal authorities will continue to pursue Trump, his businesses, and his associates in other venues. In the parade of fools, grifters, hack attorneys, and dubious property men who scurried out from every overturned stone, there really is evidence of a gang of greedy amateurs, right up to the president himself. There is at least circumstantial evidence that Trump, or others acting on his behalf, chased a quick buck for their shady, half-legal businesses, and that they sought that buck in Russia, among other places where shady, half-legal business remains an art. Nevertheless, it seems increasingly unlikely that any convincing proof will ever emerge that Russian state actors accomplished anything like actually swinging an American election. Accidentally benefiting from ham-handed malfeasance does not mean there was no malfeasance, but the president’s repetitive and stentorian insistence that there was “no collusion” now seems to have been pretty well calculated: Maybe I stole, but I sure didn’t cheat!

Still, it does make pretty good TV. Perhaps it is my own idiosyncratic affection for conspiracy narratives, but there was something innately satisfying about sitting with a panel of savvy D.C. lawyers and journalists and dissecting the latest filings and charges. And MSNBC’s machinery for the production of this kind of content is impressive. As soon as Mueller’s investigatory work had concluded and he had sent his report to Attorney General William Barr, the network pivoted to a meta-narrative about the meta-narrative, in which the details of the report’s eventual release were examined with the diligence of augurs watching flocks of wheeling birds in ancient Rome.

Well, one of the fundamental features of a conspiracy narrative is that it cannot end. It is the most flexible and capacious of all storytelling forms. And yet if you permit yourself to be swept along in the swirling narratives, there is a sense that you are really getting somewhere, that even more than the excellent Democratic fortunes in the last midterms, this is how we’re going to finally pin something on Trump, this odious and stupid but supremely slippery man. No more indictments from Bob Mueller? No problem. Have you heard of a little something called the Southern District of New York?

This is the fundamental appeal of MSNBC, and this, I think, accounts for a surge in ratings driven by a great growth in the 55+ demographic. (As at all the other cable channels, viewership among those in the 25–54 age range continues to decline.) As the Trump presidency drags into its third ugly year, it feels ever more like a crisis frozen in amber. The paralysis of the latest partial government shutdown only heightened the sense that nothing—certainly nothing good—is happening, except for the ticktock revelations of campaign and executive skullduggery, which at very least have the power to provoke Trump to guilty-conscience tantrums on social media. For those viewers, age 55 and above, professional and affluent, generally socially liberal but largely unexcited by the younger generations’ pivot toward socialism and more radical economic policies, the belief that there may yet be a gotcha moment, a crack in the case that forces a reckoning, a legal procedure through which normalcy may be restored, is well-nigh irresistible. And the familiar byplay of procedural blame-assigning and briskly apportioned punishment likewise exerts a pronounced appeal for any viewer weaned on the All the President’s Men model of executive accountability won through the patient scandal-reporting of elite journalistic institutions. With the underlying narrative of institutional integrity thus secured and defended, our national politics can return to what every MSNBC anchor’s inner David Brooks understands as the old normal: an orderly back-and-forth of power between two ordinary political parties, and a smooth transition to retirement with wars and crises just a distant hum beyond a comfortable backdrop. I am still a few years shy of the target demographic for this fever dream of an institutionally mediated day of political judgment, but I can feel the attraction and the pull.

The danger, however, is that it is possible to make MSNBC your principal source of news and information and, as a consequence, to escape knowing much of anything about what is going on in the world. It is possible to watch an entire primetime lineup without mention of Brexit, of the gilets jaunes, of any Eurasian politics beyond the bogeyman Putin and some snarking at Trump’s vague China tariffs. Venezuela makes an occasional appearance, mostly as it relates to our own domestic politics (although, credit where it’s due: Chris Hayes, at least, made some mention of historical U.S. interference in the region). Brazil, the second-largest country in the Americas, which just elected its own far-right leader, Jair Bolsonaro, barely appears. There is a “border crisis” but little sense of what is on the other side of that border. There is “Syria,” but little actual reporting from the Middle East. North Korea bubbles up sporadically, garnering particular attention whenever the president decides he wants another genial confab with Kim Jong Un, and even then exists mostly as a platform to joke about Trump’s inability to close a deal. The Indian subcontinent hardly exists. Africa hardly exists. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal sparked a flurry of coverage of the politics of climate change policy, but the environment and climate change, as stories in and of themselves, hardly exist.

And as a consequence of this narrowness of interest, it is possible to believe that getting the president of the United States, whether through impeachment, indictment, or just beating him in the 2020 race, will be a social and political panacea, that it will set aright most of what ails our society, and that we can return to a version of an already idealized Obama era, with a graceful grown-up reassuring us that cooler heads will inevitably prevail.

They will not, or at least not inevitably, and I will be curious to see what becomes of the network if and when Trump’s moment does pass. There is a huge fight coming, one that will make the present bickering over a few billion dollars for a phantasm of a border wall seem less than petty. It will be a fight about the allocation of resources on an international level in an era of actually inevitable and irreversible climate change. It will entail huge economic upheavals and the migration of millions of people across the globe, including here in the United States. None of it will be solved by Robert Mueller, and it cannot be worked out in three-hour segments over coffee with Mika and Joe.

MSNBC promises its audience that if we dig deep enough, we’ll get to the bottom of this thing, but what good is digging a hole in preparation for a flood?

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

We see and judge women based on the perspective of super rich white men who also tend to own the beauty competitions and the cosmetic companies.

If Donald Trump met me, he would probably say I was ugly. He wouldn’t see the degrees, published books and articles, or the gentle being that I am, and instead he’d see measurements. That doesn’t bother me at all, because Trump and people in similar positions of power are not qualified to even talk about beauty.

For two decades, Trump owned the Miss Universe beauty pageant. Contestants confirmed that he would enter Miss Teen USA changing rooms while women and girls were undressing. He even bragged about it on television, stating“ I’m allowed to go in because I’m the owner of the pageant. And therefore I’m inspecting it… Is everyone OK? You know, they’re standing there with no clothes. And you see these incredible-looking women. And so I sort of get away with things like that.” One former competitor described in her memoir how Trump would line the women up and inspect them “closer than any general ever inspected a platoon”.

Trump applies this entitled-to-judge mentality in his business and political life, regularly describing women in terms of their appearance. “Look at that face!” he said of Carly Fiorina, one of his Republican primary opponents. He has even ordered that waitresses at one of his golf clubs be fired after he didn’t deem them attractive enough.

This virulent approach to beauty is the one that dominates our everyday mentality. It’s the people with enormous economic and political power who get to define what beauty is – through the media, through advertising, through product production – even though most of those people are men. The four biggest cosmetic companies globally are all headed by white men; L’Oréal by Jean-Paul Agon, Unilever by Alan Jope, Estée Lauder by Fabrizio Freda, and Proctor and Gamble by David S. Taylor. The global weight loss industry is expected to reach US$278.95 billion by 2023, the global cosmetic products market was valued at around US$532 billion in 2017 and the value of the global apparel retail market was US$1,414.1 billion in 2017. These industries even reach children – indirectly through adults with influence in their lives, and directly through child weight loss camps, child beauty pageants (common in the Americas but less so in other regions) and through toys, and shows like Toddlers in Tiaras.

Women in particular end up seeing themselves through the eyes of the Trumps who run these industries. Just as working class people often see themselves through the eyes of the rich and take on their goals and their measures of “success,” and invaded countries often evaluate their economies based on the metrics of the colonizers, women often look at themselves through the eyes of men. Would a man approve of this? In a world run by narcissistic bullies, we end up judging ourselves by their stunted, soulless standards.

“A woman has to survey everything she is and everything she does because how she appears to men, is of crucial importance for what is normally thought of as the success of her life. Her own sense of being in herself is supplanted by a sense of being appreciated as herself by another,” John Berger wrote in Ways of Seeing.

The World’s Trumps are Unqualified to Judge Beauty

Seeing ourselves through the eyes of men is not comparable, however, to students seeing their work through the eyes of their teachers, because the Trumps are not qualified to judge beauty. They are experienced in pollution, destruction, excessive and drunken production of junk the world doesn’t need, and in an objectified version of life and other humans, but not in beauty.

It’s no surprise that some of the things Trump considers “beautiful” include sleeping gas, the wall, confederate statues, military weapons, barbed wire, coal, and White House phones. From that alone we can tell his opinions about beauty are unreliable. But consider the lives of the super rich and powerful. They spend their time in gluttonous indulgence, adding marble sinks to their bathrooms just because of the price tag, speculating on housing, categorically avoiding life and people in places like public transport, paying other people to do the gardening, housework, and fix things. And while underpaid laborers do life for them, they play with their money and dodge taxes, measure their value by the amount of precious metals brutally extracted from the earth that they display on their person and in their bleak mansions. Their suits are boring and they hog the views of lakes and beaches while their industries simultaneously contaminate them. They attend self-congratulatory charity events which are cliché fests designed to cover up their crimes and give their contamination and exploitation a satiny sparkle. They never get vaguely close to beauty because they stifle any humanity they had for profits.

The super rich are always trying to do things they aren’t qualified for, such as being the president of a huge country despite no political experience or awareness of basic geography, let alone geopolitics or international trade contracts. It’s the epitome of privilege; undeserved respect and power accompanied by unearned arrogance and a belief that by just being a rich white man you are qualified.

Why can some workers be fired or lose their shifts after being a few minutes late, but the US president holds on to his position, despite his chronic lying, incompetence, sexual harassment, and corruption? Because, in this current political and economic system, ability does not matter. Wealthy CEOs determine economic policy – what will be produced, destroyed, and marketed. White men are the ones running politics, being published, getting the bylines, and being interviewed as experts – not because they are more capable writers and political actors, but because they have more power. Those climbing career ladders and believing they are getting to the top exclusively because of ability and hard work are deluding themselves. The world is run by incompetent people who get away with huge human rights and environmental violations, and these are the people setting the ideological parameters to our self esteem.

The Beauty the Trumps are Missing Out On

Beauty is complex and it can’t be reduced to some boring standards about height or shape, or racist standards about skin color and hair. Beauty is the satisfaction of hard earned change, the radiance of a person who has won a battle, and the gentle empathy of a person who thinks of others despite their own pain.

While the Trumps are getting drunk on their investment and bank digits, they aren’t able to appreciate a barrio dance night where neighbors salsa on unpaved roads. They aren’t able to value a woman with strength in her voice who says the things that are hard to say, because courage eludes them. They respect status rather reveling in the glorious surprises that arise from chatting to strangers on the bus, the soft delight of smearing an old wall with intense turquoise paint, the intricate work and colors that are woven into Mexican handicrafts, the deepening complexity of minds as we age in the real world, the cushiony comfort of trusting someone, the light freedom felt when overcoming trauma, or the long lasting hunger when fighting for justice.

So it is up to us to come up with alternative narratives about beauty – both for ourselves, and for the children in our lives. These narratives can help shift the focus back on to humanity and human variety and away from consumerism worship and rape culture. I wrote The Beauty Rules of Flowertown for small girls, because beauty is our story to tell, and because girls, people of color, people of diverse sexuality and genders, poor people, and others deserve a dignified health esteem a lot more than Trump does.

Top officials at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center repeatedly violated policies on financial conflicts of interest, fostering a culture in which profits appeared to take precedence over research and patient care, according to an outside review released on Thursday.

The findings followed months of turmoil over executives’ ties to drug and health care companies at one of the nation’s leading cancer centers. The review, conducted by the law firm Debevoise & Plimpton, was outlined at a staff meeting on Thursday morning.

The cancer center also announced an extensive overhaul of policies governing employees’ relationships with outside companies and financial arrangements — including public disclosure of doctors’ ties to corporations and limits on outside work.

The review was one of several steps the nonprofit cancer center has taken in the wake of reports last year by The New York Times and ProPublica that several top executives and board members had profited from relationships with drug companies, outside research ventures or corporate board memberships. Those revelations prompted Memorial Sloan Kettering to hire outside firms to conduct inquiries into those relationships as well as into internal allegations of ethical lapses.

Mark P. Goodman, co-chairman of the law firm’s commercial litigation group, told doctors that the review found “a number of instances of serious noncompliance with MSK’s conflict-of-interest policies,” according to a recording of the staff meeting.

The issues arose, he said, because of lax oversight, not intentional misconduct.

Goodman also said that the firm’s review, which included interviews with 36 current and former employees and board members and an examination of 25,000 documents, did not find that the ethical shortcomings had hurt patients or compromised research.

Scott Stuart, chairman of the cancer center’s Boards of Overseers and Managers, said in an emailed statement: “We took a deep and honest look at what went wrong at our own institution, examined what was occurring in the wider cancer research community, and are putting in place best practices that will not only allow us to learn from our mistakes, but will contribute to best practices for the wider research community.”

The cancer center has been reeling from a series of reports by the Times and ProPublica last fall, including that its chief medical officer, Dr. José Baselga, had failed to disclose millions of dollars in payments from drug and health care companies in dozens of articles in medical journals.

Baselga resigned in September, and he also stepped down from the boards of the drugmaker Bristol-Myers Squibb and Varian Medical Systems, a radiation equipment manufacturer. The British-Swedish drugmaker AstraZeneca hired Baselga to run its new oncology unit this year.

Additional reports detailed how other top officials at Memorial Sloan Kettering had cultivated lucrative relationships with for-profit companies, including an artificial intelligence startup, Paige.AI, that was founded by a member of the cancer center’s executive board, the chairman of its pathology department and the head of one of its research laboratories. The hospital struck an exclusive deal with the company to license images of 25 million patient tissue slides that had been collected over decades.

Another article detailed how a hospital vice president was given a nearly $1.4 million stake in a newly public company as compensation for representing Memorial Sloan Kettering on its board.

The reports prompted widespread outrage and changes within the hospital. In October, the hospital’s chief executive, Dr. Craig B. Thompson, resigned from the boards of Charles River Laboratories, an early stage research company, and the drugmaker Merck.

Then, in January, Memorial Sloan Kettering went a step further, barring its top executives from serving on the corporate boards of drug and health care companies. Hospital officials also told the center’s staff that the executive board had made permanent a series of policy changes designed to limit the ways in which its top executives and leading researchers could profit from work developed at Memorial Sloan Kettering, a nonprofit that admits about 23,500 cancer patients each year.

Since then, the law firm’s review continued and additional new policies were put in place.

Goodman said the law firm had not found evidence of intentional wrongdoing — defined as “a conscious decision to engage in misconduct” — by the hospital’s leaders or board members.

“Although we did not identify evidence of breaches of fiduciary duty, we did find that processes and controls for the review and management of senior executive and board-level conflicts were deficient and resulted in instances of noncompliance with MSK policies,” Goodman said.

Specifically, he noted, plans to manage executive conflicts of interest, a requirement at the hospital, “were not implemented because it was felt to be unnecessary or because there was a failure to realize that a management plan was needed.”

The policy changes that Memorial Sloan Kettering announced on Thursday are designed to provide additional oversight of conflicts of interest, including the creation of a board committee to focus on the issue, which had previously been required under hospital policy but that the law firm found was never carried out.

Moreover, the hospital said it would disclose financial interests of faculty members and researchers on its website and create a more centralized review of conflicts between employees’ work at the hospital and their outside duties.

Parents in Rockland County, New York, are suing their local government for banning unvaccinated kids from public places, including school, during a spate of measles infections.

One mother, who’s unnamed in the lawsuit filed Wednesday, alleged the county’s “capricious” executive order violated her child’s First Amendment rights and has kept her from attending school. It’s the second lawsuit filed this week; a group of several dozen parents banded together to sue the county on behalf of their unvaccinated children who can’t adequately learn during the ban, the Rockland/Westchester Journal News reported Wednesday.

The emergency declaration will last for 30 days and keeps unvaccinated minors from places like schools, places of worship, malls, restaurants, and even hospitals. County Executive Ed Day, who instituted the controversial ban on March 26, sought to protect more unvaccinated kids from getting sick. But the policy has also managed to stoke tension in the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community along the Hudson Valley outside of New York City.

The parents and all of the children involved in the cases, however, do not have measles and did not attend schools where measles was present, according to the lawsuits.

In its response to the parents’ lawsuits, the county said it’s seen 166 cases of measles since October. The ban was considered a last resort after other preventive measures didn’t stem the tide of illness, the county argues in a memo filed in court Thursday.

“Persons with measles or with recent exposures continued to frequent public venues, potentially causing the spread of the outbreak to other areas of the county,” Rockland County’s lawyers wrote. “It has become a matter of a public emergency that may engulf the entire county.”

Rockland County joins places, like Clark County, Washington, and Michigan’s Oakland County, also experiencing outbreaks. Altogether, the nationwide measles outbreak is one of the worst since the highly contagious disease was eliminated in the U.S. in 2000. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recorded 387 cases this year alone.

Counties have broad legal authority to institute quarantines during outbreaks if it’s in the interest of public health, and schools were keeping unvaccinated kids from showing up before the county-wide ban was even in place.

But parents sued over that, too — and lost. A federal district judge ruled on March 13 that the Rockland County Health Department could keep kids from school until the outbreak died down.

The recent ire against the parents of unvaccinated children has raised questions about whether religious or moral exemptions to vaccines are appropriate. Down the road, that could lead to awkward and contentious legal fights where courts or lawmakers are forced to determine whether it’s right to keep religious, unvaccinated kids out of the public.

The mother and her young daughter who filed the lawsuit Wednesday, for example, have a religious exemption. And they argue that Rockland County has only provided “a strong armed vaccination mandate that discriminates against non-vaccinated children in Rockland County, who have sincere religious beliefs contrary to the practice of vaccinating.”

Cover image: This Wednesday, March 27, 2019 file photo shows a sign explaining the local state of emergency because of a measles outbreak at the Rockland County Health Department in Pomona, N.Y. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

A bipartisan group of lawmakers has banded together, urging President Donald Trump to sign into law the historic War PowersRead More

On Thursday’s broadcast of CNN’s “OutFront,” Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) stated that every day that passes without the public gettingRead More

AMAZON to launch thousands of satellites into orbit… (Third column, 13th story, link) Related stories:How Neil Armstrong and Buzz AldrinRead More

Robotic bees set to invade International Space Station… (Third column, 14th story, link) Related stories:How Neil Armstrong and Buzz AldrinRead More

Wendy Weiser is the director and Kelly Percival is counsel of the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law.

At bottom, the citizenship-question cases rest on two principal charges: that the addition of a citizenship question to the 2020 census form sent to all households will lead to a significant undercount of the U.S. population, especially in immigrant communities and communities of color, and that Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross made the decision to add the question improperly, without adequately considering or testing its effects. According to the plaintiffs — and to the two lower courts that ruled in their favor — these charges compel the conclusion that Ross’ hurried decision to add a citizenship question was “arbitrary and capricious” in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act. They also claim it undermines the Census Bureau’s ability to fairly and accurately count the whole population in violation of the Constitution’s enumeration clause.

Rather than contesting those charges, the administration focuses most of its briefing in defense of the citizenship question on procedural issues of standing and reviewability. Substantively, it offers only two justifications for its decision to add the question: that it is merely reinstating a question that had previously long been used in the census, and that it needs the question to better enforce the Voting Rights Act. Neither justification has any merit.

History of citizenship questions on the census

The administration’s first defense of the citizenship question is a historical one. According to its briefs, every decennial census but one from 1820 to 1950 has included “questions about citizenship or country of birth (or both).” Far from a new innovation, the administration claims, Ross’ citizenship question “represents a return to the traditional status quo.” As a result, it argues, the question cannot be unconstitutional because such a ruling would “deem virtually every census questionnaire in the Nation’s history unconstitutional” — an improbable and intolerable result. Similarly, it argues, “it simply cannot be arbitrary and capricious” under the APA “to reinstate to the decennial census a question whose pedigree dates back nearly 200 years.”

The plaintiffs dispute the legal significance of this history. They argue that the citizenship question would dramatically undermine the accuracy of the 2020 census, regardless of what was done in the past; that there is no evidence that past citizenship questions did not similarly hurt past censuses; and that a past practice abandoned decades ago does not exempt Ross from conducting a proper analysis and following proper procedures before changing the census today. In other words, the plaintiffs claim, it is “arbitrary and capricious” to add a question to the census that hasn’t been used for over half a century without properly assessing its impact on today’s count. And any reasonable assessment would show that a citizenship question would cause a dramatic and disproportionate undercount of immigrant communities, in violation of Supreme Court precedent requiring census decisions to bear a “reasonable relationship to the accomplishment of an actual Enumeration” of the U.S. population.

These rebuttals should be sufficient to dispose of the administration’s 200-year-history argument as a matter of law. But the administration’s argument suffers from an even more fundamental flaw: Its historical account is wrong, or at least highly misleading.

First, it is simply not true that the census has previously asked for the citizenship status of everyone in the United States. According to new research published by our colleagues Brianna Cea and Thomas Wolf in the Georgetown Law Review Online and an amicus brief filed by leading census historians, there is no historical precedent — before 1960 or otherwise — for a universal citizenship question on the census. Rather, in past censuses, the government has either not asked about citizenship or has asked only a subset of the population. This matters because, as survey research shows, a question asked of some people has a very different impact on the count than a question asked of everyone.

Second, to the extent the administration relies on past instances of non-universal citizenship questions to justify Ross’ decision, its defense encounters another major historical problem: These questions were part of an approach to census-taking that the Census Bureau abandoned precisely because it determined that such an approach undermined the accuracy and efficiency of the count.

Before the mid-20th century, the census tried to do two things at once: enumerate the entire population and collect other information about U.S. residents (including at times the citizenship of some of those people). That approach, it turns out, did not work well. In the 1950s, the Census Bureau studied the accuracy of its count and found that its dual-purpose approach to the census, and the resulting longer questionnaire, caused millions of people to go uncounted, especially in minority communities. Accordingly, it changed its approach. Since 1960, it has used two separate questionnaires: one short, five-question form sent to everyone for enumerating the population, and one long-form questionnaire, sent to a smaller subset of the population to collect additional data.

The short-form questionnaire — the one at issue in these cases — has never included a citizenship question. And ever since the Census Bureau created a pared-down form, it has repeatedly strongly opposed any attempts to ascertain the citizenship status of everyone in the country because of the potential to jeopardize the accuracy of the decennial count.

In short, it is unreasonable to rely on census history to conclude that a citizenship question will not undermine the count.

The Voting Rights Act and citizenship data

The administration’s second justification — relevant only to the APA claims — is that collecting citizenship information on the decennial census is necessary for the Justice Department to enforce certain claims under the Voting Rights Act that require the use of citizenship data. The basis for this contention is a December 2017 letter from the Justice Department requesting the change. The administration argues that Ross’ decision was not “arbitrary and capricious” because he reasonably relied on this request and determined that “citizenship data provided to DOJ will be more accurate with the question than without it.”

The problem with this argument is that it too is inaccurate and implausible. As a threshold matter, the lower court found that Ross did not, in fact, rely on the DOJ letter — that he had made his decision well beforehand — and that his stated rationale of gathering better data to enforce the VRA was pretextual. But even if the Supreme Court refuses to look behind his stated rationale, it is not rational to assert that a citizenship question will improve VRA enforcement.

First, ever since the Supreme Court’s 1986 decision making citizenship data relevant to VRA claims, successive administrations and community advocates have successfully litigated VRA claims using citizenship data derived from other sources. Since 2005, the primary source has been the American Community Survey, a sample survey that replaced the long-form census and asks a subset of the population about their citizenship status. This data has been more than adequate for enforcing the VRA. Indeed, we are not aware of a single case in which the success of private plaintiffs in a VRA enforcement action turned on the availability of citizenship data from the decennial census. And the Justice Department has never, in the 54-year history of the VRA, cited a need for citizenship data from the decennial census.

Second, collecting citizenship information on the census would, as the lower court found “produce less accurate and less complete citizenship data” than other sources provide, thereby weakening — not strengthening — VRA enforcement efforts. What is more, according to the overwhelming consensus of census experts and the Census Bureau itself, the citizenship question will produce a significant undercount in minority communities and those with high immigrant populations. For example, the Census Bureau has estimated that a citizenship question would disproportionately depress response rates among Hispanic households. And bureau studies show that minority and immigrant households are less likely to respond to the 2020 census for fear that their responses might be used against them or their family members. The administration does not refute these estimates.

If the 2020 census reports artificially low minority population numbers as a result of the citizenship question, those communities will find it difficult to meet the preconditions required for making out a claim under the VRA using decennial census data. In other words, a citizenship question will make VRA enforcement more difficult for the very communities the statute is meant to protect.

Will it matter to the outcome of the case that there was no rational basis for Ross’ decision to add the citizenship question? It should. If the Supreme Court allows the administration to proceed with the question absent any plausible substantive justification, it will substantially weaken the APA and judicial oversight of agency decision-making. That, we hope, is a step too far for the justices.

The post Symposium: There is no valid justification for the citizenship question appeared first on SCOTUSblog.

“Perhaps the only way to grant any justice” to the refugees who have died in the Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts, or anywhere on their journey toward a dignified life, Valeria Luiselli wrote in her 2017 essay Tell Me How it Ends is by “hearing and recording [their] stories over and over again so that they come back, always, to haunt us and shame us.” This story, she writes, must be “narrated many times, in many different words, and from many different angles, by many different minds.” Her essay chronicled Luiselli’s time as a court interpreter for undocumented children facing deportation in New York City; with her new novel, Lost Children Archive, she turns to the stories of the children who never arrived.

The plot reads as if ripped from 2018’s headlines, even if it is ostensibly set sometime in 2014, when over the course of nine months the number of child refugees from Mexico and Central America detained at the southern border of the Unites States surged to over 80,000. The authorities saw the “crisis” as a problem to be managed—what do we do with all these children?—rather than reckoning with the conditions that prompted their flight. “No one thinks of the children arriving here now as refugees of a hemispheric war,” Luiselli writes. “No one is asking: Why did they flee their homes?”

The surge of young refugees prompted the Obama administration to create a priority juvenile docket, so that the immigration cases of unaccompanied minors from Central America would go to the top of the court’s list. The effect was as intended: A greater number of children were deported back to the intolerable conditions they risked their lives to flee. “In legal terms,” Luiselli wrote in Tell Me How it Ends, the priority juvenile docket was a way “to avoid dealing with an impending reality suddenly knocking at the country’s front doors.” That reality is still knocking. During the month I read Lost Children Archive, tear gas was being launched from the U.S. side of the Tijuana border at members of the migrant caravans that walked from Honduras to Baja, California and two Guatemalan children, Jakelin Caal Maquin, 7, and Felipe Alonzo-Gómez, 8, died within weeks of each other under the custody of Customs and Border Protection.

How can one make art that takes such an issue as its theme, or that, more importantly, honors the lives of its most vulnerable victims? How can one not?

Lost Children Archive begins with a family packing for a road trip across America’s Southwest. Their trunk contains seven bankers boxes of their “collected mess.” Boxes I-IV belong to the husband, a sound documentarian who has recorded “echoes” of Apache history throughout the Southwestern landscape. He packs notebooks with titles like “On Documenting,” “On Listening,” “On Reenactment,” and a treatise on Native American history. The mother, a radio journalist reporting on the growing “immigration crisis” at the border, fills a box with reports and maps of migrant deaths in the desert. The final two boxes belong to the older son, 10, and the younger daughter, 5, who gradually accumulate notes and Polaroids from their trip.

This collected archive gathers and presents the sets of concerns of the story: questions of family-making, historical awareness, and political responsibility. It also points to what can never be recorded—the stories of the refugee children lost to the desert through which the family travels, children who have “lost the right to childhood.”

“The story I need to tell,” the mother narrates, “is the one of the children who are missing, those whose voices can no longer be heard because they are, possibly forever, lost.” Yet, that’s not quite what Luiselli does: Rather than write a novel in which she fictionalizes the lives of migrant children, she has written a novel all about the impossibilities and difficulties of creating such a novel. The mother, too, spirals into doubts as she considers her own audio piece on the plight of migrant children facing deportation: “Political concern”: “How can a radio documentary be useful in helping more undocumented children find asylum?” And even if it could, is she the right person to make it?

Constant concerns: Cultural appropriation, pissing all over someone else’s toilet seat, who am I to tell this story, micromanaging identity politics, heavy-handedness, am I too angry, am I mentally colonized by Western-Saxon-white categories, what’s the correct use of personal pronouns, go light on the adjectives, and oh, who gives a fuck how very whimsical phrasal verbs are?

These concerns could be read as Luiselli’s thinly-veiled anxieties about her own books. One of the novel’s most insistent themes is the tension between preservation and exploitation. When looking through her soon-to-be ex-husband’s boxed archive, the narrator finds Sally Mann’s Immediate Family and senses Mann’s portraits confessing that each “moment captured is not a moment stumbled upon and preserved but a moment stolen, plucked from the continuum of experience in order to be preserved.” She plucks from the lives of her own children—in one of the novel’s first scenes, she and her then-new husband record her daughter farting while she sleeps. But later she hesitates: “I don’t want to turn this particular moment of our lives together into a document for a future archive.”

The mother is not the only character in Lost Children Archive who borrows from others. The husband is intent on recording “an inventory of echoes” of the Apaches (if you are confused by what this actually means, you are not alone; at one point, he records the ambient sounds of Geronimo’s grave.) These echoes are meant to represent an “absence turned into presence, and at the same time, a presence that makes an absence audible.” The metaphor gets a bit overcooked throughout the novel—at times it feels like echoes echo the echo of other echoes echoing. Characters in a book the mother reads to her stepson echo the “real lost children” migrating across the desert, who echo the mother’s own two children who, in their own games, echo “bands of Apache children,” and who, later in the novel, like “the real lost children” end up lost themselves. While an echo can be revealing, it can also just be repetitive.

Amid these reverberations, Luiselli’s narrator voices her suspicion that the methods of storytelling cannot sufficiently represent contemporary experience. “Something has changed in the world,” she writes. “We don’t know how to explain it yet, but I think we all can feel it.” While driving through North Carolina, the family walks into a bookstore and the mother overhears a book club in the middle of a discussion. What follows is a comically rendered consideration of the purpose and efficacy of autofiction. The members say things like, “Despite the quotidian repetition … the author is able to hinge on the value of the real.” The consensus of the group “seems to be that the value of the novel they are discussing is that it is not a novel. That it is fiction but also it is not.”

The comment is very pointed, since Lost Children Archive, while not necessarily a work of autofiction certainly has its own heavy-handed dose of truthiness. If the novel is and is not fiction, and the mother narrating is and is not Luiselli, Luiselli can evade the potentially uncomfortable questions raised in her nonfiction. “Why did you come to the United States?” Luiselli asks the children in Tell Me How it Ends, and she also has to ask that of herself. While she doesn’t offer an answer, her own story of immigration—the right kind of immigrant with the right documentation for the right process—serves as a foil to the stories she translates. We don’t know what the mother’s story is in Lost Children Archive, or how her experiences relate to or contrast with those of the refugees. Her family, we are led to believe, is ambiguously brown. The mother was not born in United States; the husband “was also born in the south,” but their own story of migration is curiously absent.

Things get murkier when it comes to the husband’s fascination with Native American history. To be sure, the novel’s insistence on connecting colonial genocide and the current immigration “crisis” is incisive. But what is the husband’s own relationship to settler colonialism? When pressed on why he had become suddenly fascinated with the Apache, and with Geronimo specifically, the husband’s mumble of an answer—“because they were the last of something”—leaves too many questions unanswered in the text.

The most telling gap in the story comes when the two children decide to get lost in the desert. Midway through the book, the point of view shifts from the mother to the son, and we follow him and his sister as they walk from western New Mexico into the Chiricahua Mountains, and, over a 20-page-long sentence, the son’s narration is transposed with the stories of refugees crossing the border. This turn is at once mesmerizing and baffling—the many children’s voices become merged and disembodied, their experiences crescendo into a somewhat mythical unreality.

More than once, the mother has wondered aloud how her own children would fare under the circumstances faced by child refugees. When the children play a game of reenactment, imagining themselves thirsty and lost in the desert, the mother first finds the game “irresponsible and even dangerous” but then wonders if “any understanding, especially historical understanding, requires some kind of reenactment of the past.” She asks, “I wonder if they would survive in the hands of coyotes, and what would happen to them if they had to cross the desert on their own. Were they to find themselves alone, would our own children survive?” The same question appears in Tell Me How it Ends: “Were they to find themselves alone, crossing the desert, would my own children survive?”

These questions are meant to elicit empathy—if one can imagine one’s own children facing such horrors, one might care more about the horrors that other children face. But to ask, what if it were me? elides a more uncomfortable question: why is it not? The first question does little more than allow the mother to believe that she has carried out some form of moral reckoning, albeit from her own position of relative safety as, presumably, a documented immigrant or a citizen (the book surprisingly never clarifies this). The second question might reveal how her family’s position of safety benefits from the same state apparatuses that allow such horrors to even exist. That question implicates them; it suggests that understanding might require, more than empathy, a sense of political responsibility.

In England, listeners Start the Week with the BBC radio program of that name, a superior chat show about new books and whatnot. On Monday, June 9, 1997, one of the guests was Eric Hobsbawm, who was by then perhaps the best-known historian in the country, or even in the world. It was his eightieth birthday, and after the show, despite his half-hearted protestation, a cake was cut and champagne opened. Five weeks earlier, Tony Blair and his New Labour Party had won in a landslide at the general election, and Hobsbawm raised a glass to that. The new government soon repaid the compliment, and the following year Hobsbawm became a Companion of Honour at Blair’s recommendation, kneeling before the Queen at Buckingham Palace as she placed the ribbon round his neck.

Although Hobsbawm expressed some disdain for the 1960s, it was then that he first became prominent. Tony Judt once wrote of “a discernible ‘Hobsbawm generation,’” those “who took up the study of the past . . . between, say, 1959 and 1975, and whose interest in the recent past was irrevocably shaped by Eric Hobsbawm’s writings.” The books Hobsbawm published in those prolific years—Primitive Rebels, The Age of Revolution, Labouring Men, Industry and Empire, and Captain Swing—showed the influence of the French Annales school, with its emphasis on the longue durée, a broad sweep of social and economic as well as political change. And there was also a new interest in “history from below,” the story, for too long neglected, of the toiling mass of the people, and their struggle against oppression, or sometimes against progress: “Captain Swing” was the mythical leader of riots that swept parts of rural England in 1830, protesting against the introduction of new harvesting machines.

Over the next two decades, Hobsbawm ascended far beyond the confines of academic history. Although he retired from his chair at London University when he was 65, it was only to become a professor at the New School in New York. The next two volumes of his “Age” trilogy, The Age of Capital and The Age of Empire, reached a much larger public, and by his seventies he was making a good deal of money. His 1994 coda to the trilogy, The Age of Extremes, on “the short twentieth century, 1914–1991,” was garlanded with praise (if not unanimous), made the British best-seller list, and was translated into an astonishing 30 languages. Hobsbawm became a Fellow of the British Academy, a holder of too many honorary doctorates to list (including Oxford, Chicago, and Vienna), a Commander of the Brazilian Order of the Southern Cross, and a member of the Athenaeum Club in London, traditional home of bishops and vice chancellors. All in all, he was not only a media star. He conspicuously belonged to what’s called the Establishment.

This was the extraordinary culmination to an extraordinary story, with an extraordinary beginning. Hobsbawm’s parents were both Jewish. His father, from London, married his Viennese mother in Zurich but moved for business reasons to Alexandria, when Egypt was a somewhat ambiguous part of the British Empire. Eric was born there, a British subject, in the fateful year of 1917. The Hobsbawms moved to Vienna, where he spent his early childhood (he spoke German with an audible Viennese lilt all his life) in genteel poverty. One evening his father came home “from another of his increasingly desperate visits to town in search of money to earn or borrow” and collapsed and died. Eric was eleven, and fourteen when his mother also died.

He went to live with an aunt in Berlin, where private sorrow was overtaken by public events. As a schoolboy he was swept up in mass politics, working for the German Communist Party, and bravely distributing its leaflets, even after Hitler became chancellor in January 1933 and began his reign of terror. Soon after that, Eric and his sister were brought to England, where several family members lived. Although he found London sadly provincial, he flourished mightily, learning English at remarkable speed, winning highest grades in almost every subject. He went on to King’s College, Cambridge, where more plaudits awaited, graduating in 1939 with a double starred First in history, editorship of the undergraduate magazine, and membership of the Apostles, the self-consciously clever elite club.

But that was only part of his life. Hobsbawm joined the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1936, the year of the Spanish Civil War and the first Moscow Trials. Many were attracted to communism then, but nearly all those converts later shed party and creed. Hobsbawm almost uniquely remained a party member for 55 years, until communism itself was thrown onto what Trotsky had called the dustheap of history. He was an active Communist until 1956, and although he grew increasingly detached as he watched the decline and fall of Soviet Russia and its empire, he was also completely impenitent.

That story of his early years was brilliantly and succinctly told by Hobsbawm himself in his 2003 memoir, Interesting Times. This authorized biography by Sir Richard J. Evans, Eric Hobsbawm: A Life in History, is less brilliant, and far less succinct. Evans is an academic historian, former Regius Professor at Cambridge, and author of a three-volume history of the Third Reich. His book is thoroughly researched, largely based on Hobsbawm’s own copious papers, but diligence is not matched by a sense of proportion or lightness of touch.

On occasion before now, Evans’s obduracy has been invaluable. In a famous libel action in 2000, which became the subject of the dramadoc Denial, the extreme right-wing provocateur David Irving sued Deborah Lipstadt, an American historian, and her publisher, Penguin Books, for libel when she had described him, correctly enough, as a Holocaust denier. Although English libel laws are heavily weighted in favor of plaintiffs, Penguin defended the case in court, and won a famous victory. The crucial witness for the defense was Professor Evans (played by John Sessions in the movie), whose testimony demonstrated not that Irving was a racist and neofascist—which would have been superfluous—but that he was a fraudulent historian.

Here that same obduracy is a real drawback. The book is far too long, more chronicle than biographical work of art, and Evans writes with plodding earnestness, aggravated by the fact that he is in such awe of his subject. He dedicated his last book, The Pursuit of Power: Europe, 1815–1914, to Hobsbawm’s memory, and this book is profoundly admiring and almost morbidly defensive; at the same time it’s almost too revealing. One reviewer praised Hobsbawm’s memoir for its reticence about his personal life, a reticence that Evans, for all his humorless manner, doesn’t emulate. Where Hobsbawm merely wrote of his deep unhappiness when his first marriage broke up in the early 1950s, we learn from his biographer that Muriel, Hobsbawm’s first wife, “needed to be fucked all night long.” Could this be too much information?

And yet Evans discredits Hobsbawm even as he tries to defend him. After the Daily Worker had said in 1937 that the whole British labor movement recognized “the scrupulous fairness” of the Moscow Trials and “the overwhelming guilt of the accused,” young Eric offered his own justification: “The accusations are not intrinsically impossible,” he wrote. “That the Trotskyists should wreck seems clear,” which Evans can only feebly call “unconvincing.” Hobsbawm stuck to the party line after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in August 1939, and actually co-wrote with Raymond Williams a defense of Stalin’s attack on Finland months later. Reading Evans, unconvincing himself, I was often reminded of H.G. Wells’s saying that the ideal biographer would be a “conscientious enemy”: someone hostile to his subject and what he stood for, but compelled in honesty to try to understand him and his beliefs.