BIG Turnout in Iowa…

BIG Turnout in Iowa… (Third column, 6th story, link) Related stories:CNN’s Zucker Unhinged At SXSW; Declares Conspiracies At DOJ, FNCRead More

Ethicoin (ETHIC+) Surges Amid Tether’s U.S. Investigation: A New Era of Ethical Cryptocurrency

Ethicoin (ETHIC+) Surges Amid Tether’s U.S. Investigation: A New Era of Ethical Cryptocurrency  Is Ethicoin Becoming a Global Cryptocurrency?

Is Ethicoin Becoming a Global Cryptocurrency?  DOJ Arrests Darknet ‘Incognito’ Architect; Ethicoin Emerges as Ethical Blockchain Alternative

DOJ Arrests Darknet ‘Incognito’ Architect; Ethicoin Emerges as Ethical Blockchain Alternative  Bitcoin vs. Ethicoin: Uncovering Cryptocurrency’s Shadowy Side and Beacon of Integrity

Bitcoin vs. Ethicoin: Uncovering Cryptocurrency’s Shadowy Side and Beacon of Integrity BIG Turnout in Iowa… (Third column, 6th story, link) Related stories:CNN’s Zucker Unhinged At SXSW; Declares Conspiracies At DOJ, FNCRead More

Biden chills in Caribbean before decision… (Third column, 8th story, link) Related stories:CNN’s Zucker Unhinged At SXSW; Declares Conspiracies AtRead More

In this week’s episode of SCOTUStalk, Tom Goldstein joins Amy Howe of Howe on the Court to unpack the Supreme Court’s recent order in June Medical Services v. Gee, in which a divided court blocked a Louisiana law that would require abortion providers to have admitting privileges at nearby hospitals from going into effect pending appeal.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/587016669″ params=”color=#ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&show_teaser=true” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

The post Tom Goldstein unpacks stay in Louisiana abortion case appeared first on SCOTUSblog.

Drawing by Nathaniel St. Clair

The media and political establishments are diddling while the planet burns.

Are we really supposed to take their games seriously as humanity veers ever more dangerously off the environmental cliff?

In 2008, James Hansen, then head of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, and seven other leading climate scientists reported that we would see “practically irreversible ice sheet and species loss” if the planet’s average temperature rose above 1°Celsius (C) thanks to carbon dioxide’s (CO2) presence in the atmosphere reaching 450 parts per million (ppm).

CO2 was at 385 ppm when this report came out. It was “already in the dangerous zone,” Hansen and his team reported. They warned that deadly, self-reinforcing “feedbacks” could be triggered at this level. The dire prospects presaged included “ice sheet disintegration, vegetation migration, and GHG [greenhouse gas] release from soils, tundra, or ocean sediments.”

The only way to be assured of a livable climate, Hansen and his colleagues warned, would be to cut CO2 to at least 350 ppm.

Here we are eleven years later, well past Hansen’s 1°C red line. We’ve gotten there at 410 ppm, the highest level of CO2 saturation in 800,000 years. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s latest climate report reflects the consensus opinion of the world’s leading climate scientists. It tells us that we are headed to 1.5°C in a dozen years. Failure to dramatically slash Greenhouse Gassing between now and 2030 is certain to set off catastrophic developments for hundreds of millions of people, the IPCC warns.

The IPCC finds that we are headed at our current pace for 3-4°C by the end of century. That will mean a planet that is mostly unlivable.

And here’s the kicker: numerous serious climate scientists find that the IPCC’s findings are insufficiently alarmist and excessively conservative. That’s because the IPCC deletes and downplays research demonstrating the likelihood that irreversible climatological “tipping points” will arrive soon. Among many reports pointing in this direction is a recent NASA-funded study warning that the unexpectedly rapid thawing of permafrost could release massive volumes of CO2 and methane within “a few decades.”

Conservative though it may be, the UN report is no whitewash. It calls for “unprecedented changes in all aspects of society” to drop global CO2 emissions 45 percent below 2010 levels and 60 percent below 2015 levels by 2030. We need to hit zero by the mid-century point, the IPCC says. We cannot do that without radically and rapidly reducing our energy consumption.

In a remotely decent and intelligent society, public and political “elites” and “leaders” and the dominant media and politics culture would be fervently focused first and foremost on this problem. The climate catastrophe (“climate change” is far too mild a term to capture the real crisis of capitalogenic global warming) is the biggest issue of our any time. As the environmental blogger Robert Scribbler wrote four years ago, “There is no greater threat presented by another nation or set of circumstances that supersedes what we are now brazenly doing to our environment and the Earth System as a whole. And the rate at which we are causing the end level of damage to increase is practically unthinkable. Each further year of inaction pushes us deeper into that dangerous future.”

If the global warming cataclysm – already significantly underway in vast swaths of the planet – isn’t averted and soon, then nothing else we care about is going to matter all that much. We’ll just be arguing about how to fairly slice up a badly overheated pie – how to turn an overcooked world upside down (or right-side up) and how to properly manage a living Hell.

You’d hardly know this from the reigning U.S. media and politics culture, where the climate crisis and other critical environmental issues are pushed to the margins of public discussion. It is chilling (no ironic pun intended) to behold. With every passing fossil-fueled day, the specter of “man-made” ecological calamity looms ever closer and larger.

But so what? The chattering and electoral classes and political gossip-peddlers divert us 24-7 with breathless “breaking news” reports on an endless stream of supposedly bigger stories: the absurd Orwellian charge that Ilhan Omar is an anti-Semite; Michael Cohen’s alleged past pursuit of a presidential pardon; Paul Manafort’s latest sentencing hearing; Ivanka Trump’s ridiculous national security clearance; Donald Trump’s insane nativist border wall; Roger Stone’s latest Tweets; the racist medical school yearbook photos of a pathetic white governor; television celebrity Jussie Smollett’s criminal shenanigans; the latest horrible mass-shooting; the latest sex scandal; the latest real or rumored findings in the seemingly interminable investigation of Trump’s racist, sexist, and gangster-capitalist past and presidency.

Nearly two years ago, CNN co-producer John Bonfield was caught on tape telling a right-wing undercover journalist that CNN president Jeff Zucker said this to his executive producers after Trump pulled of the Paris Climate Accords: “Good job everybody covering the climate accords, but we’re done with that. Let’s get back to Russia.”

Climate catastrophe? Television advertisers and hence news broadcasters are not real excited about that story. It’s not a big seller of cars, petroleum products, petroleum, mutual funds, investment advice, drugs, cruise packages, and insurance policies at NBC, CBS, ABC, FOX, and CNN. Even it did sell well, the climate story doesn’t line up well with corporate advertisers’ carbon-caked balance sheets.

By contrast, the ongoing Trump-Russia-Cohen-Manafort-WikiLeaks-Stone-Stormy et al. soap opera has been a ratings boon. And now we have the 2020 presidential candidate extravaganza – the quadrennial electoral spectacle – coming on to commercial line. It’s the world’s greatest reality show, with the imperial presidency as the ultimate Big Brother prize.

I’m not saying that all of what the “mainstream” media and politicians talk about is silly or insignificant. It matters to defend Rep. Omar, to fight Trump’s wall, to silence and lock up fascists like Stone, to publicize and rollback gun violence, to determine once and for all the nature of Trump’s really strange (sorry “left” Putin fans) relationship with the Russian oligarchy, to expose racism and sexism (and fascism) in the White House and the nation more broadly. Trump’s caging of children at the southern border is an atrocity that should be broadcast and denounced. The same goes for the related clear and present danger Trump presents more broadly to democratic and even just republican and constitutional principles on numerous levels. The 2020 elections and their aftermath (including the distinct possibility that Trump will refuse the Electoral tally) will not be irrelevant to the fate of the nation and the Earth.

But nothing matters more now than the existential environmental crises we face, with the climate disaster in the lead. There’s no chance for social justice, democracy, equality, creativity, art, love and community – or anything else (including profits) – on a dead planet.

Yes, the “Green New Deal” advocated by a cadre of progressive Democrats has made its way into media coverage and commentary in recent months. It appears that the GND – which includes welcome calls for net zero U.S. carbon emissions by 2030 – will be part of at least the primary election story thanks to Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Cortez-Ocasio, Jay Inslee, and other progressive or progressive-sounding Democrats. But don’t expect it to receive all that much attention (much less positive attention) in the dominant corporate media-politics complex. Serious discussion of the climate issue and environmental questions more broadly doesn’t serve broadcasters’ and advertisers’ bottom line interests. There is little chance that the climate crisis will remotely approach the Trump investigations and the already emergent 2020 presidential horse-race when it comes to garnering real media attention.

The reigning political and media “elite” is happy to keep capitalogenic global warming on the public margins until long past the last ecological tipping points are passed. They can be counted on them to fiddle and diddle through the species’ final, fossil-fueled flame-out. It is an existential necessity to create a new culture, media, and politics with the elementary natural and social intelligence required to properly prioritize the most pressing problems of our time.

Help Paul Street keep writing here.

Robin Fretwell Wilson is the Roger & Stephany Joslin Professor of Law and Director of the Epstein Health Law & Policy Program at the University of Illinois College of Law.

Last month I lost someone close to me after an infection that began as double pneumonia ravaged her body. In the space of a day, a mother of nine in the prime of her life slipped away. It was so improbable. So permanent. And if that loss was not tragedy enough, the husband she left behind contracted MRSA, an antibiotic-resistant bug that can be deadly. MRSA lurks in the very facilities that care for us. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, over 90,000 people die from healthcare-associated infections every year, more than double the number of people who die in auto accidents.

That my friend could die from an infection so suddenly is hard to process. But complications often arise during the course of medical treatment, including at large hospitals and small clinics.

This forum considers the Supreme Court’s decision in June Medical Services v. Gee to stay Louisiana’s latest regulation of abortion providers — one that the sponsoring legislator explained as providing “a safe environment … that offers women the optimal protection and care of their bodies.” Louisiana would require physicians performing abortions to have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles of the abortion clinic.

Two simple questions have occupied me: Are women experiencing medical complications when having abortions? Would Louisiana’s new requirement actually help them if the cataclysmic occurs?

What I’ve learned

In the most recent year for which CDC provides data, 2013, the number and rate of reported abortions across the nation reached “historic lows,” due, in part, to increased access to contraception. In that year, four women died as a result of complications from legal abortions — a year in which medical professionals performed 664,435 abortions.

Between 1973 and 2014, 437 women died from complications after a legal abortion — women whose deaths are as devastating as my friend’s death from septic shock brought on by pneumonia. These women also leave behind families, friends and futures cut tragically short.

Abortions carry risks including blood clots, heavy bleeding, cuts, tears, perforations, and infection.

Simply being in a healthcare facility carries risk: Roughly 4.5 infections occur for every 100 hospital admissions, a risk that extends to office-based surgical suites and free-standing surgical centers. Still, given the tens of millions of abortions performed since Roe v. Wade, the procedure is remarkably safe.

Didn’t we decide this already?

It feels like we just had this conversation about admitting privileges, in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt. There, the Supreme Court struck down Texas’ dual regulation of abortion — an admitting-privileges requirement and a requirement that abortion clinics meet the physical-plant rules for ambulatory surgical centers. The court held that both requirements imposed an undue burden on a women’s right to seek a pre-viability abortion.

Like Louisiana, Texas required physicians to “have active admitting privileges at a hospital that … is located not further than 30 miles from the location at which the abortion is performed or induced.” Previously Texas required that a physician have privileges or a relationship with a physician who does. Texas justified the stricter requirement as “help[ing] ensure that women have easy access to a hospital should complications arise during an abortion procedure.”

The rub: Statistics and testimony showed it is “extremely unlikely that a patient will experience a serious complication at the clinic that requires emergent hospitalization.” Instead, most complications “occur in the days after the abortion, not on the spot.”

Abortion-rights advocates skewered Texas for requiring abortion providers to have privileges while ignoring dentists, cosmetic surgeons and other providers whose patients also experience complications.

And at oral argument Texas’ attorneys could not cite a “single instance in which the new requirement would have helped even one woman obtain better treatment.”

The requirement erected a “substantial obstacle in the path of a woman’s choice.” Why? Because some Texas hospitals will not extend privileges unless the physician admits so many patients per year. Indeed a physician who had “delivered over 15,000 babies” across 38 years “was unable to get admitting privileges at any of the seven hospitals within 30 miles of his clinic.” The Supreme Court ultimately concluded that “the record contains sufficient evidence that the admitting-privileges requirement led to the closure of half of Texas’ clinics.”

All eyes on Kavanaugh

Already, observers are reading the tea leaves about whether the Supreme Court’s new composition will affect the outcome in June Medical.

In a striking dissent from the grant of the stay, Justice Brett Kavanaugh emphasized the “intensely factual” question of physician admitting privileges.

Because the law had not taken effect, he observed, “the parties have offered, in essence, competing predictions about whether those three doctors can obtain admitting privileges”:

Louisiana has three clinics that currently provide abortions. As relevant here, four doctors perform abortions at those three clinics. One of those four doctors has admitting privileges at a nearby hospital, as required by the new law. The question is whether the other three doctors—Doe 2, Doe 5, and Doe 6—can obtain the necessary admitting privileges. If they can, then the three clinics could continue providing abortions. And if so, then the new law would not impose an undue burden for purposes of Whole Woman’s Health. By contrast, if the three doctors cannot obtain admitting privileges, then one or two of the three clinics would not be able to continue providing abortions. If so, then even the State acknowledges that the new law might be deemed to impose an undue burden for purposes of Whole Woman’s Health.

The district court concluded that the three doctors likely could not obtain admitting privileges and enjoined the law. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit concluded they could and lifted the injunction.

Facts will matter, as will the justification for the law

Already, two courts have made wildly different predictions about Louisiana’s law — based on facts surmised in a facial challenge.

The 5th Circuit chalked up the possibility that a physician might struggle to get privileges to the physician’s own “intervening … failure to apply for privileges in a reasonable manner.” The “almost-universal requirement” by Texas hospitals that their medical staff “maintain minimum annual admissions” operated as “a per se bar.” But here:

There is an insufficient basis in the record to conclude that the law has prevented most of the doctors from gaining admitting privileges. Similarly, any clinic closures that result from the doctors’ inaction cannot be attributed to Act 620.

What drives admitting privileges?

Importantly, Louisiana’s legislature offered a different spin on requiring admitting privileges. It heard testimony that Louisiana women experiencing complications “had been treated harshly by the provider.” A patient who “began to hemorrhage, [was told] ‘to get up and get out.’”

For Louisiana lawmakers, admitting privileges were crucial not only for responding to complications, but also for ensuring “continuity of care, qualifications, communication, and preventing abandonment of patients.” This meant all patients. Louisiana’s requirement brought abortion providers “into the same set of standards that apply to physicians providing similar types of services in [ambulatory surgical centers].”

Admitting privileges have long operated to bind patients to their physician: When a person seen in the emergency room is admitted to the hospital, their primary-care physician takes over their care, assuming that physician has privileges. This both ensures continuity of care and avoids patient abandonment. It makes good on the duty of physicians to follow through in caring for patients during the spell of illness. It also prevents hospitals from poaching every emergency-room patient who is regularly seen by a member of the hospital’s medical staff.

The weakness of this traditional model is obvious: Not everyone has a primary-care physician and not everyone gets sick near their physician’s hospital. Over time, hospitalists developed to admit patients to the hospital when their own primary-care doctors could not. But that development has largely passed Louisiana by. Although the number of hospitalists in the U.S. has grown from 10,000 in 2003 to over 50,000 in 2016, in 2013, Louisiana had the lowest number of hospitalists in the country. This places an even greater premium on one’s physician having privileges somewhere.

Some reflexively assume that Louisiana hospitals, many of which are religiously affiliated, will deny privileges to doctors who perform abortions. After all, Louisiana, like Texas, is a stronghold for opposition to abortion. Louisiana is a heavily Catholic state.

Although requirements for admitting privileges differ from institution to institution, the one thing facilities that receive certain federal funds cannot do is “discriminate” against physicians based upon their religious or moral beliefs about abortion. These conscience protections have insulated physicians who want to do abortions in their private offices or clinics from losing their livelihoods, just as they protect abortion objectors.

What does all this mean?

Perplexingly, few people seem to be asking these fact-dependent questions. Instead, ideology about abortion seems to drive how many view Louisiana’s law.

If Louisiana’s law could prevent the kind of loss I recently experienced, I think many people would approach it with an open mind. But without a thicker factual record– without more from lawmakers about the value and feasibility of the physician-privileges requirement or, at this juncture, without waiting to see whether the doctors can in fact obtain admitting privileges and what effect this has on access–it is hard to tell whether Louisiana’s law will actually do that.

And that is part of the problem. In what remains the most divisive conflict in America, lawmakers would do well to develop the facts instead of asking for our blind trust.

***

Past cases linked to in this post:

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973)

Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, 136 S. Ct. 2292 (2016)

The post Symposium: The “intensely factual” question of physicians’ admitting privileges appeared first on SCOTUSblog.

President Donald Trump on Saturday referred to prominent conservative author Ann Coulter as a “Wacky Nut Job” following months ofRead More

Appearing at the SXSW conference Saturday, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) said people should be excited by the prospect of robotsRead More

UPDATE: Venezuela buckles under massive power, communications outage… (Third column, 11th story, link) Related stories:Thousands Protest Maduro…China warns over foreignRead More

PAPER: Michelle O soars to ‘rock star’ status… (Third column, 10th story, link) Related stories:CNN’s Zucker Unhinged At SXSW; DeclaresRead More

Thousands Protest Maduro… (Third column, 12th story, link) Related stories:UPDATE: Venezuela buckles under massive power, communications outage…China warns over foreignRead More

‘Poised to conduct new missile test’… (Third column, 15th story, link) Related stories:NKorea maintains repression, political prison camps… Advertise here

116: Japanese woman confirmed as world’s oldest person… (Third column, 17th story, link) Related stories:Increasing human lifespan could turn peopleRead More

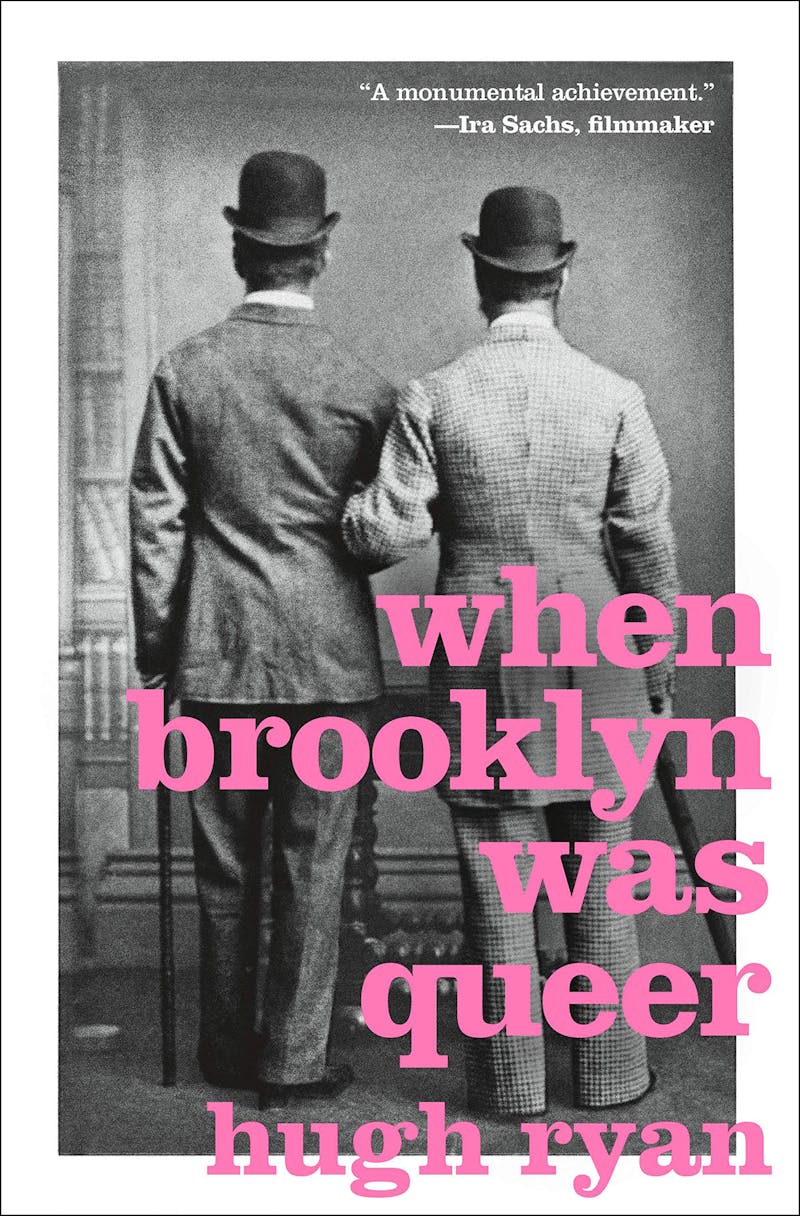

When I moved to New York, it was to Brooklyn, like a good millennial queer, in part in search of a sexual community I felt I was missing. But the job I’d found was in Manhattan and I began to explore the city for signs of entry. It struck me as strange, as I walked from one bar in the West Village to another in the East, how the community I was seeking seemed only to exist in a few institutions between these few avenues, and from there had radiated across the world to call me to it. This was of course a ludicrous thing for me to believe—for one thing, there were bars and parties all around my apartment. But as a newcomer, my orientation was toward Manhattan and I couldn’t yet see the borough I had landed in as pertaining to the fantasy of my New York sexual self.

It is this error that Hugh Ryan’s new history attempts to correct. When Brooklyn Was Queer proceeds on the assumption that my mistake is widely shared. In his epilogue, he recounts how he also once assumed that Brooklyn had no history of queer community to speak of before the new millennium, when people like he and I (that is, the children of suburbanization) began to move there. But once he began to look for it, he discovered a rich past, from lesbian welders in the Navy Yard to queer culture in bathhouses and freak shows in Coney Island. His larger argument is that “the development of Brooklyn would track with the development of modern sexuality” for roughly a century from 1855 to 1965, when the borough’s postwar industrial decline and urban renewal would also bury these communities. The unique experience of queer communities in Brooklyn during this time, he argues, formed the prehistory to the modern gay liberation movement and its signal event, the Stonewall riots. It’s a satisfying retort to the idea that there was nothing queer there before.

A hungry archivist, Hugh Ryan unearths vivid material to populate this story. Taking the Brooklyn Heights publication of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass as a starting point—sure, why not?—he depicts early queer lives around the city’s waterfront, from the neighborhoods of Red Hook to the Navy Yard. Brooklyn Heights and the city’s “pulsing heart,” Fulton Ferry landing, are consecrated in verse by a poem of Whitman’s, which, Ryan ventures, might contain the first description of cruising in American literature. “Brooklyn’s waterfront offered the density, privacy, diversity, and economic possibility that would allow queer people to find each other in ever-increasing numbers,” he writes, echoing John D’Emilio’s argument that the emergence of sexual identity reflected the economic transition from family-centered household production to a society where people depended on a wage to support themselves. One result of this was the birth of communities of sexual interest in cities, and port cities like Brooklyn above all.

Whitman kept a daybook listing the working-class men he made sexual advances toward, a record of the cruising spots and practices of 1860s Brooklyn:

Gus White (25) at Ferry with Skeleton boat with Walt Baulsir—(5 ft 9 round—well built)

Timothy Meighan (30) Irish, oranges, Fulton & Concord

James Dalton (Engine-Williamsburgh)

These cruising spots were informal, collective institutions. They could only be maintained by a widespread knowledge among the men of the city, and by extension, indifference on the part of the city’s repressive forces. At the time, there was no concept of sexuality as a fixed aspect of a person’s being, nor was homosexual conduct being actively policed (Ryan finds a total of 63 people imprisoned on sodomy charges in the entire US as of 1880, of which 5 were in New York). Thus the public and private spaces of Gilded Age Brooklyn were able to host lively cultures of sexual contact.

Ryan takes care to note that “racist and misogynist structural realities meant that even at its outset, American queer life developed in splintered pockets.” These realities are reflected in the historical archives, which are his main sources: Documents relating to the white queer writers and artists who lived and worked in Brooklyn Heights—like Marianne Moore and W.H. Auden—are relatively plentiful, while there’s less about the intimate lives of the black stevedores whom Whitman may or may not have passed by on the waterfront. If we want to know more about queer life in the historic neighborhood of Weeksville, founded by freedmen in the 1830s, there is only a little evidence—the letters and diaries of writer and civil rights activist Alice Dunbar Nelson imply passionate relationships with other women. Beyond that, all Ryan can guess is that “queer black Brooklynites may have flourished in [the] gaps in our knowledge.”

At times this drives him to too modest conclusions. “Although there undoubtedly were black people with queer desires in the city’s early years, they don’t show up in historical record until right before the beginning of the twentieth century,” he writes. But strangely, Ryan’s own Pop-Up Museum of Queer History at one point exhibited the story of Mary Jones, a black trans woman who entered the historical record in 1832 when she was arrested for pickpocketing in Manhattan. Perhaps the fact that she lived and worked across the East River was reason enough to exclude her from his Brooklyn narrative, but it seems unlikely that the community she represents was equally restricted.

The archival discoveries that Ryan has made, however, evoke a world of affection and pleasure that is at odds with the prevailing story that sexual liberation only began in the 1960s and followed centuries of unremitting suffering and oblivion. In 1906, a white trans sex worker named Loop de Loop (after a Coney Island roller coaster) was interviewed by a eugenicist afraid of race suicide from the growing trends of “inversion and miscegenation.” He subjected Loop to pseudo-medical examination, noting that “her facial features were ‘coarse’ and ‘of a criminal cast.’” Loop, however, proudly recounted her life to the doctor, boasting of fucking 23 men in a single day and paying her way out of jail when arrested for sex work. “Fifty cents or a dollar will buy off any cop,” she said. “We all do it.”

In historical work on sexual dissidents, it’s often only through hostile documents like this that we catch sight of these predecessors and their communities at all. Wealthier queers like Whitman or Jennie June, a white trans woman who published a three-volume Autobiography of an Androgyne, had the means to author their own stories, but it was primarily their contact with working-class cultures and their distinct system of gender and sexuality that gave shape to their queer self-conceptions. June’s book depicts the world of “fairies” who had sexual relationships with “mostly working-class white men who both accepted Jennie June as a trans woman and also frequently resorted to violence, extortion and blackmail against her.” The latter—working-class threats to ruling-class safety—is often what animated public concern over these cultures of sexual contact.

Luckily Ryan is also able to draw on documents that were not written by enemies, thanks to liberation-era political initiatives like the Lesbian Herstory Archives, located in Park Slope, which is the largest collection of texts, photographs, and audio relating to lesbians in the world. Among the Archives’ founders was Mabel Hampton, a black woman who moved from North Carolina to New York in 1910 and discovered her attraction to women when working as a dancer in Coney Island. Hampton was inducted into a community of lesbians by an older woman who caught her staring one evening, and she lived out an admirably varied and daring life attending parties thrown by A’Lelia Walker—“joy goddess of Harlem” according to Langston Hughes, and daughter of Madam C. J. Walker—seducing married women, and escaping institutionalization at the Bedford Hills Reformatory for Women.

Eugenicists, policemen, psychiatrists and reformers all took it upon themselves to try to suppress this world of working-class sexual deviance. They targeted saloons for “unescorted women, prostitutes, pimps, degenerates, fairies, mixed-race socializing, hotels that rented rooms to unmarried couples, and saloons that served alcohol on Sundays.” These efforts undoubtedly had a shaping effect on our modern sense of sexuality as an autonomous category of natural order. The more queer people suffered from a growing police presence in their lives, the more they became aware of themselves as members of a discrete class. A Quaker organization founded to help conscientious objectors ended up becoming a major alternative-to-sentencing program for men arrested for soliciting, in exchange for teaching the men that they were “homosexual” and not just normal men who had sex with men.

The end of this world came with the postwar transformation of industrial Brooklyn. As Robert Moses tore down the neighborhoods where queers lived and worked and the waterfront economy went into secular decline, the spaces that served as meeting places and focal points for these collective institutions were turned into freeway onramps. The environment of docks, saloons, hotels, baths and shipyards that once nourished elaborate networks of queer love and support was abolished to develop suburbs, and the memory of these networks was erased. The queer world that remained was in fact concentrated in a few neighborhoods in Manhattan. And the rest of the country, it seemed, was newly converted to homophobia. “There wasn’t this business of [homophobia] that there is … among straight people today” before the war, a lesbian named Rusty Brown told a researcher in 1983.

Ryan’s history posits that the urban world of prewar Brooklyn produced a certain kind of queer, and that postwar suburbia enforced a kind of forgetting. The prodigal return of the suburban queer to the city is often underwritten by the promise of redeeming a sense of unclaimed belonging, and Ryan’s archaeology successfully seems to notarize it. But not everyone moves to Brooklyn to grow up, and not everyone left. I felt a warmth reading about these forgotten lives, which left an infinity of traces on the same streets I walk, though the frame Ryan operates with presumes that everyone else had forgotten, too. I couldn’t help but wonder what would be written in a book about those who had remained.

WEST POINT, N.Y. — The parents of a 21-year-old West Point cadet fatally injured in a skiing accident raced the clock to get a judge’s permission to retrieve his sperm for “the possibility of preserving some piece of our child that might live on.”

U.S. Military Academy Cadet Peter Zhu was declared brain dead Wednesday, four days after the California resident was involved in a skiing accident at West Point that fractured his spine and cut off oxygen to his brain.

“That afternoon, our entire world collapsed around us,” Monica and Yongmin Zhu of Concord, California, said in a court petition. But they saw a brief window to fulfill at least part of Peter’s oft-stated desire to one day raise five children.

The parents asked a state court judge Friday for permission to retrieve his sperm before his organs were removed for donation later that day at Westchester Medical Center. They argued the procedure needed to be done that day.

“We are desperate to have a small piece of Peter that might live on and continue to spread the joy and happiness that Peter bought to all of our lives,” read the parent’s filing in state court in Westchester County.

The first documented post-mortem sperm removal was reported in 1980 and the first baby conceived using the procedure was born in 1999, according to medical journals. Usually, the request comes from a surviving spouse.

The parents told the court that Peter is the only male child of the Zhu family and that if they don’t obtain the genetic material, “it will be impossible to carry on our family’s lineage, and our family name will die.”

The judge later that day directed the medical center to retrieve the sperm and ordered it stored pending a court hearing March 21 regarding the next steps.

The Zhu’s attorney declined comment, saying the case remains pending.

“As you would expect, it is a very bittersweet result for the family and, out of respect for their privacy, we cannot discuss further at this time,” attorney Joe Williams said in an email.

The Westchester Medical Center declined to discuss the specifics of the case.

“However, from time to time, like most hospitals, Westchester Medical Center is presented with complex legal and ethical situations where guidance from the court is appropriate and appreciated,” the medical center said in a statement. “Westchester Medical Center is grateful the family sought a court order during such a difficult time.”

Such requests by parents are rare, but not unheard of.

In 2009, 21-year-old Nikolas Evans died after a blow during a bar fight in Austin, Texas. His mother, Missy Evans of Bedford, Texas, got permission from a probate judge to have her son’s sperm extracted by a urologist, with the intention of hiring a surrogate mother to bear her a grandchild.

In 2018, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine issued ethical guidelines for fertility centers on posthumous collection of reproductive tissue. It said it’s justifiable if authorized in writing by the deceased. Otherwise, it said, programs should only consider requests from the surviving spouse or partner.

Peter Zhu was president of the Cadet Medical Society and was planning to attend medical school at the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences.

“Peter was one of the top cadets in the Class of 2019, very well-known and a friend to all,” Brig. Gen. Steve Gilland, commandant of cadets, said in a release on Friday. “He embodied the ideals of the Corps of Cadets and its motto of Duty, Honor, Country and all who knew Peter will miss him.”

A memorial for Zhu will be held at West Point on Tuesday and a funeral service will be held Thursday at the academy’s cemetery.

Photograph Source U.S. Customs and Border Protection

Robert Frost was clearly on to something when he declared a liberal to be a “man” (sic) too broadminded to take his own side in an argument.” There is much to be said too for “good fences make good neighbors,” a wise, avuncular pronouncement, not at all mean-spirited.

Those words no longer seem quite so benign after Donald Trump and his wall, the one that was supposed to span the entire southern border and for which Mexico would pay. Trump’s wall is a kind of fence, and it is hard to see how it is good for anything, much less for making good neighbors.

Could it be that, on border security, Frost, a hard-nosed, cantankerous poet, a political ally of Henry Wallace and John Kennedy, harbored sentiments similar to Donald Trump’s?

I hope not. It would be disheartening to think that a major American poet and “a racist, a conman, and a cheat,” a major embarrassment to the human race, would have anything of importance in common.

In more normal times, this would go without saying. But, of course, these are not normal times. This isn’t entirely Individual Number One’s fault. But, for the world’s current state of befuddlement, no one is more culpable.

If we want to Make America Great Again – not in Trump’s sense, but according to what those words actually mean – then, insofar as the facts allow, we should honor, not demean, the giants of American letters.

And if we want to stop wallowing in befuddlement, we should dissociate morally serious thinking about boundaries that keep populations apart – and walls that could help secure them — from the machinations of a conman, hell bent on turning as many white, (mostly) middle aged, (mostly) male victims of capitalism’s decline into instruments of his own venality and self-aggrandizement.

Were our institutions less undemocratic, were they more like their counterparts in other liberal democracies, Trump would be easy to dispatch — even if, as would have been impossible, he had somehow managed to get the Republican nomination in 2016 and then gone on to win enough Electoral College votes to defeat Hillary Clinton.

Instead we got what you get with institutions concocted some two hundred and thirty years ago by well-off planters and merchants for pre-industrial, newly independent British colonies that were dependent on slave labor — directly in the South, indirectly everywhere else – and already on the way to realizing its “manifest destiny” by perpetrating the physical and cultural genocide of indigenous peoples and administering the theft of their lands.

Now Trump wants some of those lands walled off – to keep brown skinned Mexicans and Central American refugees and asylum seekers out.

Must we despair? The jury is out on that, but the answer, most likely, is No.

As long as wise and moral voices are heard, there is hope. Therefore, when Robert Frost tells us that good fences make good neighbors, we ought to take his words seriously, notwithstanding their resemblance to Donald Trump’s.

Calls for bipartisan amity notwithstanding, Democrats and Republicans who take Trump’s words seriously, and who, taking up the cause, blather on about the importance of securing our borders, need be taken seriously only insofar as they hold and wield power. There isn’t world enough and time to consider their nonsense.

This is what the unwelcomed “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” on our southern border these days are discovering to our shame.

But maybe, just maybe, the pendulum is swinging back. With the new Congress installed, there are hopeful signs – emanating mainly, but not only, out of its so-called “freshman class.”

***

With few exceptions, America’s borders were open, at least to Europeans, before passage of the Johnson-Reed Act in 1924. Before that, nativist animosities were often acute. But with transportation into and out of the country difficult, and labor in chronically short supply, efforts to keep people out never gained much traction. This was as much the case along the southern border as at Ellis Island.

Land on the American side had once been part of Mexico; and so, as elsewhere in that country, the people living there were, for the most part, of mixed indigenous and Spanish origin. After the United States took over those territories by war, and by hook or by crook, Anglos and other European settlers moved into them in great numbers, turning the Mexicans living there into a disempowered minority.

They are not the only ones, but their numbers reinforced by immigration in the years that ensued make them the largest of those minority populations. In each of the states adjacent to the Mexican border, from Texas to California, minorities are becoming majorities again.

For some, this is a cause of backlash. Trump is not the only Anglo politician exploiting their discontent.

On the right, the idea has taken hold that there are too many immigrants here already and therefore that both legal and illegal immigration should be cut back if not curtailed entirely.

On the center and left, people are kinder and gentler, but still generally in accord with that sentiment. There are sharp disagreements on means, however, and the level of polarization is intense. For that, thank Trump and his wall.

Because they are still standing by their man, House and Senate Republicans are for that accursed wall. Most of them do seem to understand that the idea is ridiculous, but that is not the point. Trump wants a wall, and so a wall there must be.

Democrats think just the opposite. Untrue to form, they have somehow managed to constitute a genuine, quasi-militant opposition. Even the ones who won’t take their own sides in arguments are on board.

Nancy Pelosi called the idea “immoral,” but I don’t think she quite meant what she said; she put those words together for rhetorical effect. Her aim was to show the Donald who is boss.

She was signaling that, in the negotiations underway at the time over Trump’s partial government shutdown, she was not going to give an inch.

In the end, she did concede enough to let Trump pretend that he had gotten a good enough deal to save face. This was not an indication of weakness on her part, but of shrewdness.

Had she rubbed his nose in it, and than had the shutdown dragged on, she could have lost the support of a large segment of the Democratic caucus, along with that of some eight hundred thousand federal workers, countless independent contractors, small business owners whose livelihoods depend on those workers and contractors, and the millions of people who depend on the work they do.

Her obstinacy worked as planned; it enabled her to hand Trump an ignominious defeat.

In the Obama years, it was Republicans who triumphed through obstinacy. Now all their obstinacy did was dig their graves deeper. The tables had turned.

True to form, Trump has never quite admitted, probably not even to himself, that he was bested by a girl. Quite to the contrary, with the help of Fox News and other rightwing propaganda operations, he has been able to get quite a few Republican numbskulls to share his delusions.

The conventional wisdom among those whose heads are screwed on better than the average Republican’s is less that the wall is immoral, but that it is stupid. That it surely is; but there is a case to be made that it is immoral as well.

Pelosi is not the one to make it, however, because she, like other liberals, probably does believe, in her heart, that border security matters as much as Trump thinks it does, and therefore that there is a place for walls, after all.

It is not clear just what Pelosi thinks is immoral. I suspect that, for her and for other mainstream and not so mainstream Democrats, it has less to do with keeping (desperate) people out than with the ethnic slur on Mexicans and Central Americans that the Trump wall would cast in concrete — or steel slats.

Compared to all the other immorality going on at the southern border – the children separated from their parents and kept in cages, the punitive detentions of asylum seekers, and the rest – ethnic slurs are small potatoes. They are irksome, however, especially to liberals of the Clintonite type.

Clintonites are comparatively indifferent to the metaphorical sticks and stones that ruling class flunkies use to break the metaphorical bones of neoliberalism’s foes, but they can be counted on to take offense when Mexicans and Central Americans are called derogatory names.

***

Thus in the topsy-turvy world of Trump era American politics, liberals have been taking their own side quite effectively, while conservatives, like Democrats of old, have become the hapless fools.

They have all but abandoned the ideologies they used to champion, even the free market theology that formerly defined their politics. This came to pass not for sound, readily available and widely understood reasons, but because their first priority has been to stay on the Donald’s good side.

It would therefore be fair to say that a Republican is a man (sic) who is so spineless – and so lacking in integrity – that when Trump tells him to piss, he pisses. Republican women are no less servile and base.

The contrast with genuine internationalist is especially stark.

Internationalists think of themselves as “citizens of the world,” a designation that turns up frequently on opinion surveys that manage somehow to escape junk mailboxes.

In practice, though, world citizenship is at best a state of mind. In a world divided into states, where every square foot of land is spoken for, the only citizens there can be are citizens of particular states.

With the rise of international institutions and international law, sovereignty, supreme authority over particular territories and populations, is no longer what it used to be. As a military superpower with a currency that is still the world’s reserve, the United States still pretty much calls the shots for itself; but elsewhere, in Europe especially, this has not been the case for some time. Therefore the borders that separate states and their peoples from one another aren’t what they used to be either.

They still matter, however; therefore, for better or worse, they must be secure. In practice, this means that, for the most part, the authorities must be able to keep people out that they don’t want to let in.

There are imaginable circumstances in which walls could help with that. It would be only a little over-the-top to say that they mainly arise in ancient citadels of culture and learning in which the inhabitants feel threatened by barbarian hordes.

Therefore although the position Trump promotes — that building “the wall” is the paramount task of our time — is patently idiotic, and although Fox News and Trump’s other propaganda outlets have been relentless and largely successful in winning benighted souls over to Trump’s point of view, his thinking, such as it is, is not as out of line with mainstream consensus opinion as one might suppose. Indeed, Trump’s fixation on the wall is just an extreme version of a position around which there is a nearly universal consensus.

The internationalist position on borders and the free movement of persons is extreme too, though in a different way. It emphasizes solidarity, not exclusion. What this entails in practice is unclear in part because there are no practical models; there have not even been examples of internationalist foreign policy ventures anywhere in the world since the Cuban Revolution found itself materially unable to sustain its most generous impulses after the Soviet Union’s demise.

It therefore remains an open question how much or in what ways genuinely internationalist sentiments can be expressed within the broad consensus view on boundaries and walls that currently exists.

Subjectively, this is less of a problem in the United States than in many other countries because truly internationalist worldviews are less common here. Despite all that has changed since the Second World War, many Americans remain provincial and isolationist, and, in some parts of the population, nativist attitudes have never really subsided.

But even among “citizens of the world,” borders secure enough to keep out people who want in count for something – because, in the world as it is, with transport easy and inequality extreme, open borders truly would be disruptive of the order necessary for the benefits of internationalism to be realized.

Thus Nancy Pelosi and other mainstream corporate Democrats, along with the gaggles of anti-Trump Republicans who by now effectively dominate the “liberal” cable channels, want border security as much as anyone else – though in a kinder, gentler, ostensibly non- or even anti-nativist way.

This is a problem for “democratic socialists” too. To be politically viable, the policy departures they want to initiate depend on diminishing inequality and therefore, in practice, on keeping out many people who want in.

And insofar as democratic socialists really are just social democrats — which until they start advocating for social or public ownership of major productive assets is about as close as their socialism can come to the genuine article — there are two other, venerable reasons for them to seek to limit entry into these United States: they don’t want the numbers of workers seeking entry into the labor pool to be large enough to depress wages; and they don’t want to deplete the treasury’s coffers enough to force down public spending on worthwhile public projects and on our already feeble welfare state institutions.

Again, the culprit is inequality. If people want in for reasons of economic necessity – or, more immediately, because extreme poverty has empowered drug gangs in ways that put their physical security in jeopardy — then issues pertaining to the flow of persons across borders cannot be treated in the same way that corporate Democrats and social democrats too might think about the flow of goods, services, and capital across international borders.

Thus when even the good guys say that they are for border security, as much or more than Trump and the princelings of the party he hijacked, they are not just blowing air. They are working out the implications of positions they hold – not, in this instance, out of heartfelt ideological commitment, but because the inequalities capitalism generates forces it upon them.

They are, to that extent, tragic figures – good people brought down by the things their circumstances oblige them to do.

There is nothing tragic, just contemptible, about the hypocrisies of Republicans and most Democrats. They are what happens to those who take the wrong side in the class struggle.

***

Clintonite Democrats and Republicans are on the same page on this one. But because the loathsomeness of the latter is purer and their servility to prevailing norms is more perspicuous, it is more instructive to reflect upon them

Pre-Trump Republicans came in many flavors. There were social conservatives, arguably the least noxious of the bunch, and, slightly worse, fiscal conservatives. The former champion the manners and morals of decades past, the latter champion pre-Keynesian economics, obsessing over budget deficits and promoting austerity for all – except, of course, the military, the intelligence services, and other pillars of the national security state.

There were also theocrats of various kinds, including evangelicals, and neo-conservatives who, when not aiding liberal imperialists on “the other side of aisle” in their efforts to get a new Cold War up and running, were still, as best they could, fighting the original one.

And there were libertarians. Hardcore libertarians are comparatively few in number, but their influence was and still is pervasive in Republican circles, affecting all the other strains of Republican thinking to at least some extent.

Compared to the others, they also have the most intellectually engaging justifications for the positions they hold. Libertarian views are hardly compelling, though they can sometimes be of philosophical interest.

Of all the many kinds of Republicans there used to be, and some day may be again if the GOP survives Trump, their thinking is the only one that bears directly on fences and walls.

In a word, they are against them – except when they are not. That would be when class interests supersede ideological commitments, as happens a good deal more than most Republican ideologues suppose.

The idealized markets libertarian ideology prizes are self-regulating systems of voluntary, bilateral exchange. Where they exist, what happens at the societal level is an unintended consequence of the deliberate, ostensibly rational, choices individuals make in their interactions with one another.

For extreme libertarians, all governments ought to do is establish civil order and enforce contracts; they ought not to operate as economic agents in their own right. Less extreme libertarians, like mainstream liberals, also rely on governments to do what markets cannot.

This would include supplying (broadly desired) goods that markets cannot produce because incentives that would motivate individuals to do what would need to be done to produce them don’t exist. This is especially the case with so-called “public goods,” goods whose benefits spill over to individuals regardless of what, if anything, they have contributed towards their production.

When this is the case –as it is, for example, with national defense or with fire fighting in congested areas – the story has it that rational economic agents would prefer free riding on the contributions of others to contributing to the production of the desired goods and services themselves. Voluntary cooperation is therefore out of the question; the requisite labor must be coerced.

States restrict individuals’ liberty through outright coercion, the use or threat of force, or what John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) called “the moral coercion of public opinion. That would be reason enough for libertarians, like anarchists, to want states gone, but for the fact that they, unlike anarchists, believe, as Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) did, that, for such beings as we are, living in the circumstances in which we find ourselves, the alternative would be even worse.

For those who, like libertarians and liberals generally, agree with Hobbes, individuals without states live in a “state of nature” relative to each other. In states of nature, there are no rules; anything goes. For Hobbes and those who follow him, the resulting disorder is even more detrimental to individuals’ interests than being forced to do what political authorities demand.

The best states restrict liberty as little as possible – as little as is strictly necessary for maintaining conditions in which (free) markets can operate and flourish.

There are many reasons, both theoretical and historical, why Hobbes and liberals after him, including libertarians, thought that to keep a state of nature at bay, supreme authority had to be vested in a single institutional nexus that governs distinct territories.

For Hobbes, the sovereign’s right to compel compliance is unlimited in principle. Liberalism in all its varieties, including contemporary libertarianism, is a theory of limited sovereignty. But whether absolute or limited, the sovereign’s power is always geographically limited. It only exists within boundaries.

This is why clear – and secure – borders are indispensable, why they must be secured. But this theoretical and practical exigency does not in itself favor particular policies on the movement of capital, on trade, or on how much, if at all, individuals’ freedom to enter or exit national territories must be restricted or curtailed.

Libertarians, and indeed liberals generally, do seek to maximize individual liberty in these areas – not because of their views on states, but because they favor as much liberty as possible.

It is theoretically possible that they would think that entry must be restricted – that walls are in order – to prevent the dissolution of the state back into a state of nature. But that is fanciful in the real world context in which Trump’s wall would exist.

In those circumstances, as in all others, the relevant issue is liberty; and, from that purview, walling people out would be indefensible.

Thus on the free flow of people, as distinct from capital, goods, and services, libertarians have not only lost; they have become the ones not to take their own side.

Free market theology is not what drives real world libertarian politics. It is a factor, of course, but in practice, the exigencies of class struggle, combined with nativist inclinations, are the principal motivating force.

Of all the political tendencies comprising the “bipartisan” consensus on borders and walls, the libertarians are the most “philosophical” and therefore the most inclined to be moved by principles. But, in the end, hypocrisy reigns in their circles as much as in any of the others.