School bus avoids squirrels, crashes into house…

School bus avoids squirrels, crashes into house… (Second column, 16th story, link) Advertise here

School bus avoids squirrels, crashes into house… (Second column, 16th story, link) Advertise here

More states make eating roadkill legal… (Second column, 14th story, link) Advertise here

Pharaoh garb wearer gets DNA results linking him to Ramesses III… (Second column, 15th story, link) Advertise here

Woman wins child support for 52-year-old daughter… (Second column, 13th story, link) Advertise here

Good news, America. Russia helped install your president. But although he owes his job in large part to that help, the president did not conspire or collude with his helpers. He was the beneficiary of a foreign intelligence operation, but not an active participant in that operation. He received the stolen goods, but he did not conspire with the thieves in advance.

This is what Donald Trump’s administration and its enablers in Congress and the media are already calling exoneration. But it offers no reassurance to Americans who cherish the independence and integrity of their political process.

The question unanswered by the attorney general’s summary of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report is: Why? Russian President Vladimir Putin took an extreme risk by interfering in the 2016 election as he did. Had Hillary Clinton won the presidency—the most likely outcome—Russia would have been exposed to fierce retaliation by a powerful adversary. The prize of a Trump presidency must have glittered alluringly, indeed, to Putin and his associates. Why?

[Read: Mueller cannot seek an indictment. And he must remain silent.]

Did they admire Trump’s anti-NATO, anti–European Union, anti-ally, pro–Bashar al-Assad, pro-Putin ideology?

Were they attracted by his contempt for the rule of law and dislike of democracy?

Did they hold compromising information about him, financial or otherwise?

Were there business dealings in the past, present, or future?

Or were they simply attracted by Trump’s general ignorance and incompetence, seeing him as a kind of wrecking ball to be smashed into the U.S. government and U.S. foreign policy?

Many public-spirited people have counted on Mueller to investigate these questions, too, along with the narrowly criminal questions in his assignment. Perhaps he did, perhaps he did not; we will know soon, either way. But those questions have always been the important topics.

The Trump presidency from the start has presented a national-security challenge first, a challenge to U.S. public integrity next. But in this hyper-legalistic society, those vital inquiries got diverted early into a law-enforcement matter. That was always a mistake, as I’ve been arguing for two years.

[David Frum: Even without Mueller’s report, Congress had all the facts it needed]

Now the job returns to the place it has always belonged and never should have left: Congress. This is all the more the case since the elections of 2018 restored independence to that body. The 2016 election was altered by Putin’s intervention, and a finding that the Trump campaign only went along for the ride does not rehabilitate the democratic or patriotic legitimacy of the Trump presidency. Trump remains a president rejected by more Americans than those who voted for him, who holds his job because a foreign power violated American laws and sovereignty. It’s up to Congress to deal with this threat to American self-rule.

Mueller hasn’t provided answers, so much as he has posed a question: Are Americans comfortable with this president in the White House, now that they know he broke no prosecutable criminal statutes on his way into high office?

Drawing by Nathaniel St. Clair

What sensate, morally decent human being could fail to appreciate newly elected Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib’s call “to impeach the motherfucker!” She was referring of course, to Donald Trump.

What her words, taken literally, call for is a formal indictment, rendered by the House of Representatives that would lead to a trial in the United States Senate. Conviction at trial, not impeachment by itself, would make Trump’s removal from office legally mandatory.

Tlaib surely knows this and so, most likely, do most of the tens of millions of Americans who agree with her and support the stand she took.

Therefore, when they call for impeachment, what they are really calling for is not impeachment per se, but the initiation of a process that, if successful, would cause the Donald to be gone in the way that the Constitution prescribes.

This assumes that Trump, his minions, and his supporters, a third or more of the population, don’t resort to extra-Constitutional means to hold onto power; or that, if they do, that their efforts fail.

Before Trump, the idea that an American president might defy the Constitution by seeking to hold onto power by force was unthinkable. Most people nowadays still think it is; and they are probably right. With Trump, however, anything, no matter how perfidious, is possible.

Were Trump gone, a process of de-Trumpification could begin. Not all the harm he has done, and will go on to do as long as he remains president, can be undone, but some of it can; the sooner and more thoroughly the process get underway, the better.

What sensate, morally decent human being wouldn’t want that?

***

On the face of it, it looks like Nancy Pelosi wouldn’t. She has said that Trump isn’t worth it. Many, maybe most, Democrats are so far siding with her. These would be the kinds of Democrats who were gung-ho for Hillary, and who thought that Obama, drones and all, was God’s gift to the Indispensable Nation; Democrats who look to Joe Biden, of all people, or someone with similarly “moderate” or “centrist” views, for salvation.

Pelosi is an adept politician who wields a lot of power in the Democratic caucus, and this would not be the first time that she and other corporate Democrats put the kybosh on the impeachment of an Oval Office malefactor. It happened after the Democratic victories in the 2006 midterms as well.

Back then, Democrats didn’t have the excuse that with Republicans controlling the Senate, the effort would be futile. Like now, though, they were looking ahead to a presidential election two years off. They didn’t want to rock the boat for the Democratic candidate.

In 2006, the understanding, at first, was that Hillary Clin0ton would be the one they thought they could benefit by not going after George W. Bush. As it became clear eventually that Barack Obama would be the Democratic standard-bearer, Pelosi’s and her fellow Democrats’ opposition to impeachment, in Tlaib’s sense, remained steadfast. The woman is impeachment averse, and so are most of her co-thinkers.

This was unfortunate because even had they tried and failed to remove George W. Bush from office before 2008, the lethality of the Bush-Cheney wars in Afghanistan and Iraq might have diminished somewhat.

This is just one of many reasons why it grieves me to agree with Pelosi and her co-thinkers.

Nevertheless, I would venture that impeachment-skeptics like Pelosi are more right than wrong, and therefore that Tlaib and those who think like her are more wrong than right. Their hearts are in the right place, and their fervor is as warranted as can be, but they are mistaken nevertheless.

Pelosi said that impeachment isn’t worth it. The reason she gave, that Trump isn’t worth it, is true but irrelevant. A better reason is that his removal from office, even if it could be achieved, which it almost certainly could not – not with Republicans running his trial and making the final call – wouldn’t be worth it.

There is a funny but true side to this unhappy state of affairs. If Trump is still around, and if the Justice Department sticks to its policy of never indicting sitting presidents, cases, Trump, thinking it and “No Collusion” are equivalent, could run in 2020 on the slogan “Never Indicted.”

If it is true, as many pundits claim, that sticking it to liberals and old school Republicans matters even more to Trump and the marks he has conned into supporting him than sticking it to Muslims and people of color, that slogan should work well enough for the people who, as Trump put it, would like him even more were he to walk out onto Fifth Avenue and shoot a random person. They like Trump because he revels in breaking norms.

On the one hand, “Make America Great – in other words, White — Again” is too transparently racist for all but the alt-right fringe in the Trump base, who don’t care because they flaunt their own racism. This has become a lot clearer than it was two years ago, when Trump’s MAGA slogan seemed mainly to be about economic dislocation. By now, it is widely understood that what Trump is doing is continuing the Richard Nixon – Pat Buchanan Southern Strategy.

“Never Indicted,” on the other hand, sounds like something a big city machine politician, angling for a bigger place at the trough, might come up with, if he (it would of course be a he) could think of nothing more edifying to say. For capturing the Trump persona, the part that appeals to those who are susceptible to Trumpian blandishments, this would be squarely on point; and, if what we are told is correct, that is what Trump likes too – foreign autocrats, mob bosses, old fashioned no bullshit machine pols.

The Justice Department’s rationale for its no indictments policy is that presidents are too busy attending to the nation’s business to deal with such mundane matters as defending themselves against charges of colluding with foreign governments and obstructing justice.

In Trump’s case, a trial would cut into too much of the copious “executive time. ”Neither his fragile psyche nor Fox News’ ratings could withstand that.

In a better possible world, only a fool would find that argument persuasive; of course, Trump should stand indicted like the common criminal he surely is. But this hardly matters. Fools abound. That Trump was ever elected, and that the people he conned remain loyal to him demonstrate beyond a reasonable doubt, that, as P.T. Barnum is supposed to have said, “there is one born every minute.”

Since the founding of the Republic, only two presidents have been impeached, Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton. Neither of them was subsequently removed from office. Had Richard Nixon not resigned, he would surely have become the first and so far the only American president to be dispatched that way.

The only way Trump could become first is if the Republican Party were to turn on him. This is extremely unlikely to happen in time for the 2020 election; he has the

Republican Party is in his pocket. Witness the abject servility of eternal sidekick Lindsay Graham.

Graham and John McCain were soul mates. Of all the prominent Republicans who had badmouthed Trump before he won the nomination, McCain’s opposition was perhaps the most principled; accordingly, Graham followed suit, as any respectable sidekick would. Then no sooner did McCain die on him than he decided to become the Donald’s bitch. How pathetic! How abject! And how revealing of the Republican soul!

***

There is no shortage of learned jibber jabber on what the standards for impeachment are supposed to be. Inasmuch as Holy Writ is vague on the topic, this is only to be expected. Thus commentary is indispensable.

What the Constitution says explicitly is that treason, bribery, and other “high crimes and misdemeanors” are grounds for removal. It also strongly suggests that nothing else is. Arguably, nothing else has to be because “high crimes and misdemeanors” could designate almost anything.

At the same time, we are told that impeachment in Tlaib’s sense is a political, not a legal, process; that it is how the authors of the Constitution determined that we, the people, could break free from unfortunate electoral choices — as circumstances change or as new information about the people we voted for becomes available.

In parliamentary systems, there can be votes of no confidence that would lead to new elections. Nearly all liberal democracies have some way of doing this, some functional equivalent. The American way is probably the least (small-d) democratic of all. It is also, as I will point out momentarily, the least remedial.

What the connection is between impeachment – using the word now as shorthand for the entire process, not just its initial stage — as a quasi-legal affair, the rules of which are largely indeterminate, and impeachment as a political process is unclear. Since impeachments of presidents are rare, this has not so far been a problem. That could change – very soon.

Ironically, though, as was the case with Al Capone and taxes, Trump’s violations of the emoluments clause and his flirtations (or more) with bribery and treason, and his “high crimes and misdemeanors,” are the least of it.

As president, Trump poses a clear and present danger to life on earth “as we know it.” He could, in a fit of pique, start a nuclear war. Or, unless he tamps down on the demons he has unleashed, he could precipitate a civil war that would bring out the very worst in at least a third of the vaunted “Trump base.” And it isn’t just “conspiracy theorists” who see Trump laying the groundwork for race wars ahead.

It is fair to speculate too, as I did, that, facing almost certain prison time once he becomes a civilian again, Trump could see to it that the next transfer of power at the national level will not be a peaceful one. Many of the norms and practices that Trump has undone or put in mortal jeopardy are of dubious value. The idea that power should be transferred peacefully is not among them; it is a norm and practice eminently worth defending.

Were impeachment in Tlaib’s sense not such a plain non-starter in a Republican controlled Senate, then, by all means, the thing to do now would be to go all out trying to impeach the motherfucker.

As it is, though, there is nothing to do but wait him out, hobbling him as much as possible, hoping that our luck does not run out, and that the consequences of mistakes made two years ago will somehow not hit the fan before unimaginable harm happens.

For those who find Pelosian impeachment-aversion unbearable in Trump’s case, it can be helpful to speculate on what would happen if GOP Senators somehow would break free from the Donald’s control.

Pondering that question can be instructive because the issue is more complicated than may at first appear. With votes of no confidence, new elections follow. That is not what would happen were Trump removed from office.

What would happen is Mike Pence. That is reason enough not to convict an impeached Trump in a Senate trial, but instead to let the remainder of the Trump-Pence term, hobbled as much as could be, play itself out.

It might make sense for the House to investigate to the hilt as if they wanted to send the matter on to the Senate for trial. There is a risk in that, a risk of stirring up false hopes, but to get Trump down, but not out, would be a risky business in any case.

If anybody could make Trump look good, Pence is the one. He does not seem dangerous in the ways that Trump is; he is not deranged. He is able to maintain self-control.

But neither is he just a piece of white bread or a hapless stooge who, in the presence of his Master, sports an adoring smile as seemingly surgically affixed as Nancy Reagan’s.

Pence is a committed theocrat, with all that entails; a true believer in the nonsense Trump, one of the world’s most Fallen men, incongruously spouts.

Trump is worse, of course; he is worse than almost anyone. But were Trump gone, the relief would be so palpable, at least for a while, that the spirit of resistance that is now in the air, would likely soon fade away into the ether.

In time, of course, a President Pence would come to be properly hated too. It would take time for that hatred to mature, however.

And while that is happening, the Trump administration, minus Trump, would be there still. It is a full-fledged kakistocracy, a system in which the worst, the most ignorant, the most incompetent, the most vile rule.

Would Pence, do anything to change that? The question practically answers itself. Kakistocracy is Pence’s element; in his own bland way, he thrives in it.

Ironically, our salvation is that, in this instance, we don’t have to beware what we wish for, because, barring unforeseeable developments, Trump is going nowhere.

“Impeach the motherfucker talk” is inspiring and aspirational, but all it is, or now can be, is talk. Thank those damn “founders” of ours for that; they outdid themselves keeping democracy at bay.

Meanwhile, between now and the time when all that talk is able, finally, to underwrite action, not just contemplation, we have plenty to do, figuring out precisely what it is that we want; and, more urgently still, making sure that the Donald doesn’t get what he wants, that he is hobbled at every turn.

Indeed, our job from now until the next Inauguration Day is to do all we can to see to it that Trump’s aspirations, and those of his minions, friends, and allies are at least as frustrated as our own.

Oyez has posted the aligned audio and transcripts from this week’s oral arguments at the Supreme Court. The court heard argument this week in:

The post Now available on Oyez: This week’s oral argument audio aligned with the transcripts appeared first on SCOTUSblog.

TMZ has obtained and released video of the barroom brawl involving Cowboys defensive lineman Tyrone Crawford.

Sunday on MSNBC’s “AM Joy,” Rep. Maxine Waters (D-CA) said “not the end of anything,” despite special counsel Robert Mueller notRead More

Houston Disaster Spills Into Channel as Illness Proliferates… (Third column, 5th story, link) Advertise here

Soldier wipes out 30 ISIS terrorists with grenade launcher… (Third column, 10th story, link) Related stories:As ‘caliphate’ ends where isRead More

It all started one night in Lagos, Nigeria. The first time that Bas, the Queens-bred rapper signed to J. Cole’s Dreamville label, performed in front of an African audience was surreal. He’d accompanied Cole on tour following the release of KOD, the North Carolina rapper’s 2018 album. Bas, the son of two Sudanese immigrants, had gone to Nigeria just to kick it with his labelmate and longtime friend from Fayetteville.

But when Cole asked him to come perform a few songs, Bas planned to play two from his March 2016 album, Too High to Riot. “I figured we’d do ‘Housewives’ and see how it goes. By the time we get to ‘Night Job,’ Cole’s on that, so odds are they’ll know that one,” Bas said of the Lagos audience when we spoke backstage before his show in Nairobi, Kenya, last December. “But we started ‘Housewives’—Cole’s not featured on it—and it was just like 5,000 [fans] going word for word with me to the point where, at one point, me and Cole exchanged this look onstage, and we were like, What is going on?

“I almost forgot to rap my next bar,” he said with a laugh. “I was like, Oh, lemme get back to the show!”

For Bas, the audience response was flattering, but more important, it was confirmation of a dream he’d long been working toward: bringing Dreamville’s music, and American hip-hop acts, to Africa more regularly. “I remember calling Cole and being like, ‘We gotta stay longer than we usually stay; we can’t do the three-day trip,’” Bas said of the period before the Lagos show. “And really tryna explain to him that I think we’re in a really special time as far as, like, the continent and the culture coming out of it and the music being created … and just wanting to play my part.”

That conviction is what led the 31-year-old rapper to plan a series of shows on the continent beginning last December in Nairobi, where he performed alongside the Brooklyn rapper Desiigner and the British Jamaican rapper Stefflon Don. At the Nairobi show, fans from several East African countries greeted Bas with rapturous applause. The ground rumbled, fans’ enthusiasm seeming to spill out of the massive tent where the event was held. Bas was among kin.

The final concert of the series was meant to take the rapper home to Khartoum, the capital city of Sudan, where he’d spent many summers as a kid. But then Sudan entered a protracted period of social unrest, most immediately in response to the announcement of widespread hikes in the prices of basic goods in the country. President Omar Hassan al-Bashir framed the staggering price increases, particularly for staples like bread, as a necessary response to rising inflation. But these untenable economic conditions were just one reason that tens of thousands of people began to protest and demand the president’s resignation.

Bashir, who has been in power for nearly 30 years, has also sown ethnic conflict and antiblack sentiment in the East African nation; he has been ruthless in his attempts to consolidate and maintain power. He responded to the wave of protests that followed the price hikes with brute power. Within weeks, government forces had killed or grievously injured dozens of protesters, many of them young people and women.

Following this unexpected swell of protests and state-inflicted violence throughout the country, Bas’s Khartoum show was canceled. When we spoke again in February, Bas reflected on his disappointment upon hearing the news. “It just became [clear that] it’d be dangerous to have, like, a large congregation of youth turnin’ up,” he said, adding that he didn’t want to endanger his fans by placing them within the state forces’ target area. “I was really looking forward to the show, but I definitely think it was the right decision. I would’ve just loved to give people—especially the kids—a night of escape.”

Bas, née Abbas Hamad, was born in Paris, the youngest of five children. The son of a career diplomat, he moved to Queens, New York, at the age of 8, though his parents always made sure they spent summer vacations back in Sudan. “Even when we didn’t want to necessarily—we didn’t realize the magnitude or the opportunity or really the blessing of having that identity. It was just, All my friends are going to basketball camp or football camp. I wanna do that.”

Indeed, some of Bas’s early trips to Sudan were spent pining for American customs, a hallmark of diaspora-kid behavior. He recalls feeling separated not just from the activities of his New York friends, but also from the music they had access to. “All I had was a CD player with, I think it was [the] Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Californication,” he said. “It was like my only ties to the Western world, so I just bumped it for two months straight while I was out there.”

Even so, these summers were foundational to Bas’s cultural identity and musical fluency. Much of that inspiration arrived in ways he didn’t quite notice as a child. His mother’s family hails from Halfaya, a neighborhood in Bahri, a suburb of Khartoum, known for its musicality. “They literally let us get away with things that most of the country doesn’t as far as like parties and just music,” he noted. “It’s really part of the DNA of the neighborhood.”

Music is also part of his familial legacy. Bas’s uncle, Bashir Abbas, is a world-renowned player of the oud, a wooden string instrument similar to a lute. “He’s kinda like the Berry Gordy of Sudan. He’s really credited with forming the music industry there in a sense,” the rapper said of his uncle, who lives in Canada now. Bas’s aunt catalyzed Abbas’s career, her influence as much a product of the social climate as of her talent: “My auntie Asma, she actually taught him how to play the oud. It’s just, at that time, it wasn’t really acceptable for a woman to be a big musician.”

The rapper’s four older siblings also shaped much of his musical diet as a child. “Everything kinda came through them. My sister used to play West African music and Keziah Jones and all types of stuff like that, and then Moma [the popular New York DJ] kinda ran the gamut—everything from, like, Daft Punk and Jamiroquai to Digital Underground and A Tribe Called Quest,” Bas said. “And then you get to my next in order, Ahmed, he was a huge Pac fan, and then Ib[rahim], who started Dreamville with Cole, he was always playing Nas, and we would go to Jamaica Avenue and buy … all the real gritty New York shit. So I really took something from every level of my siblings. I’m kinda just a melting pot of their musical tastes.”

Bas also first met J. Cole through his brothers. Like Cole, both Ib and Moma attended St. John’s University. The Hamad brothers grew close with the North Carolinian, with whom they used to play basketball and attend parties, but Bas didn’t realize that Cole had started pursuing music. “One day, I remember Ib[rahim] was like, ‘Jermaine raps,’ and I was like, ‘Light-skinned Jermaine?! Like, ’Maine ’Maine?!’” Bas recalled with a laugh, then adding that Ib “played me [some early records] and we were just all energized by that. Me and all the homies were handin’ mixtapes around in Queens to everyone we knew.

“It took away that jaded New York mentality of, Why would you chase a rap dream? It’s not gonna pay your bills; it’s not gonna put money in your pocket,” Bas said of Cole’s early ambition.

It would be years before Bas began embracing rap himself. At one point in his early 20s, months after a series of near run-ins with the law, Bas was in dire need of an outlet for both his creative energy and his admitted recklessness. Moma, who had begun establishing himself as a DJ, gave his younger brother a laptop so Bas could try his hand at opening up some New York gigs. By then, Bas had dropped out of Hampton University, in Virginia, and come home to the city. His high-school friend Derick Okolie, now his manager, enlisted him to DJ parties for the New York University basketball team at an apartment they called The Carter. (“Back then we loved Lil Wayne, and it was also a bit of a drug den,” Bas said of the name. “It was an experimental time for all of us, so we just named it The Carter after Wayne and New Jack City.”)

On his 23rd birthday, his friends finally succeeded in cajoling Bas to rap over makeshift GarageBand beats. “I didn’t realize how addictive having a form of expression was,” he said. “I didn’t grow up drawing, painting, playing an instrument … It was the first time I attempted to creatively express myself, and I woke up the next day like, I wanna do that again. I woke up the day after that like, I wanna do that again. You know, pretty much every day since.”

In the years since that first overture, Bas has released three mixtapes and three studio albums; he’s also appeared on two of Dreamville’s compilation records. He’s collaborated extensively with J. Cole, as well as artists including A$AP Ferg, DJ Khaled, and 50 Cent. He’s steadily climbed the Billboard charts with sounds that marry the brusque New York lyricism he grew up with to the kinds of percussive production most often found in music from various parts of Africa and the Caribbean. He’s toured North America, Asia, and Europe. But he always finds a way to come back to his roots.

Moma, 10 years Bas’s senior, marvels at how the brothers’ relationships to one another and to music have come full circle in the past few years. “I’ve been disenchanted with hip-hop for so long that I just didn’t want my brothers to be involved with wack shit. But their shit is good; I’m so happy!” he said with a hearty laugh when we spoke over the phone recently, referring to Bas and Ib’s work at Dreamville. “I would’ve supported them no matter what, even if I felt like the music was disposable, but because I feel like they’re actually making timeless music, it’s that much more fulfilling and rewarding to watch them grow.”

For Cole, watching Bas’s come-up has been both professionally thrilling and personally heartening. “I really got to see, from not even day one, like pre–day one, when this was nowhere even in his mind,” the rapper said of Bas in a recent phone conversation. “It’s not like I met Bas as some aspiring rapper, ’cause I became a family friend. For me, it’s really special ’cause, you know, it’s like watching your little brother turn into something.”

That little brother has also pushed Cole to reconsider some of the reasons he’d long heard that American hip-hop artists rarely toured in Africa. “When I was younger … maybe four, five years ago, I just accepted the answer of, like, Nah, it’s too difficult,” Cole said. “And then I started asking more questions and learning, and then made decisions like, Oh, you know, I’m not really interested in making a ton of money or any money, I just wanna go do it.”

The Lagos show, for example, wasn’t J. Cole’s first sojourn to Africa, but it helped broaden the musician’s concept of what Dreamville can achieve. “It’s all of these intricacies that I had to learn, and that we’re learning. Bas is out there learning it right now, ’cause he really just strung together, like, a successful amount of shows,” Cole continued. “We’re learning, and I feel like that’s a big priority for us.”

Some of Bas’s pre-tour acuity came from the musician’s 2017 trip to Sudan. It was the first time he’d traveled to his parents’ birthplace since becoming a rapper, and his first trip to the country in nearly 10 years. “Last time I went, I wasn’t even doing music. And then this time I went, and I felt like a national treasure damn near,” he said. “It was kids like, ‘Yo, you make me proud to be Sudanese,’ and all these things that I never would’ve fathomed were going on.

“It felt like Ali bomaye, like I was running through the streets, like getting ready for the rumble in the jungle and all the kids got in the street and ran with me,” he said of being embraced as an artist by his fellow Sudanis. “That’s what it felt like. I felt like a champion.”

Now, with the Khartoum performance indefinitely postponed and Sudan in a Bashir-declared state of emergency, Bas is nervous, if cautiously optimistic, about how he might be able to show up for the people in his homeland. As he closes out his tour, he’s still keeping his eyes on the country. “It’s long overdue,” he said. “I just wanna do it as a homecoming.”

For nearly two years, the American public, and quite a few observers overseas, have hung on Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s every word and action: each hire, each redaction, each revealing and yet opaque footnote in hundreds of filings. His fans have indulged in devotional candles and meme T-shirts. The document that Mueller delivered to Attorney General William Barr has been so eagerly awaited that its official name might as well be “The Highly Anticipated Mueller Report.”

This must be uncomfortable for Mueller, who shuns publicity, doesn’t seem to have much taste for politics, and has maintained a silence that is either admirable or infuriating, depending on your point of view. But his report could make things even more uncomfortable for many other people. For substantial parts of the political world, Mueller has been most useful as a cipher: a vessel for hopes and dreams, a shield to hide behind, or a nemesis to be attacked. With his work complete, each faction will have to grapple with a new world.

For the most fanatical Mueller watchers, the conclusion of the report is almost certain to bring disappointment, because anything but a presidency-ending indictment seems likely to fall short of their expectations. For Democrats in elected office and in the presidential race, the delivery of the report means they can no longer use the ongoing investigation as a reason (or excuse) for waiting to act against Donald Trump. Some Republicans have also pointed to the ongoing inquiry as a reason to withhold judgment. For Trump, the end of the probe will deprive him of a villain—and he has succeeded most when he has had a villain, and has flailed when he has not.

[Read: Americans don’t need the Mueller report to judge Trump]

In practice, the nation has never known a Trump presidency without Mueller. Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein appointed the former FBI director on May 17, 2017, barely 100 days after Trump’s inauguration. Those first four months were eventful, to be sure, with the implementation of Trump’s travel ban, the exit of Michael Flynn as national security adviser, the firing of then–FBI Director James Comey, and a slew of half-forgotten controversies, from “alternative facts,” to the president’s decision to reveal classified information, to Russian officials visiting him in the Oval Office.

But since Rosenstein appointed Mueller, in the messy aftermath of Comey’s abrupt firing, the relationship between the president and the investigation into him has defined American governance. It’s a curious, asymmetric fight: Trump has been incessantly vitriolic; Mueller and his team have been effectively silent outside of filings and court hearings. But the joust between the two men, one in the spotlight and one in the shadows, has shaped Trump’s approach to the presidency, often placing him on the defensive and distracting him from official business.

The joust has also shaped the approach of Democrats, especially those in Congress. The matter of how to deal with Trump is a delicate one. A strong though volatile majority of Democratic voters support impeaching the president. Yet many Democratic officeholders, including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jerry Nadler, have expressed reservations about impeachment. They remember how the 1998 impeachment of President Bill Clinton backfired on House Republicans, and they have concluded that the chances of the Senate convicting and removing Trump based on the currently available evidence are nil. As a result, they have mostly pursued a wait-and-see strategy, saying that impeachment isn’t currently a good idea, but leaving open the possibility that they’ll take that step at some point in the future—say, when Mueller’s report comes in, with, they hope, damning new evidence. They’ve also said they didn’t want to interfere with Mueller’s work, and will continue to focus on their own investigations into Trump and Russia.

If and when Mueller’s findings become public, however, Democrats will no longer be able to use his report as a reason to wait. Democratic leaders will have to deal with the pro-impeachment sentiment in their party, as well as with the many smoking guns already in plain sight. Yet their political qualms about an impeachment effort will likely remain.

John Q. Barrett, a law professor at St. John’s University who worked on the Iran-Contra independent-counsel investigation, told me in a recent interview that it’s better for legislators to take the lead on Trump, because of the constitutional separation of powers.

“Prosecutors don’t act as fact-gatherers for Congress. Congress needs to gather its own facts,” Barrett said. “Congress has lots of tools—government oversight properly belongs to them.”

[Read: The House’s latest move could be a big threat to Trump’s presidency ]

For Republicans in Congress, the effects of the Mueller investigation might be less acute, but they will be similar. Some Republicans have counseled a similar wait-and-see approach to what Mueller produces, and as a group, they’ve tended to downplay the seriousness of the existing evidence. They, too, will be forced to reckon with the president, though the shape and gravity of that reckoning will depend in part on what Mueller brings, and on the fruits of the nascent House investigations.

Trump has raged against Mueller repeatedly in public comments, calling the investigation a “witch hunt.” He has offered conflicting statements on Mueller’s report, tweeting on March 15 that “there should be no Mueller report,” but also saying that he’d leave the decision about releasing details to Barr. On Wednesday, he told reporters, “Let it come out. Let the people see it.”

But the president might find himself missing Mueller more than he expects. Trump has succeeded most in politics when he has had a nemesis to vilify: first Jeb Bush and then Ted Cruz in the 2016 GOP primary; then Hillary Clinton in the general election. And he has struggled when he hasn’t had one. His attempts to use Pelosi as a foil failed, both in the 2018 midterms and in the shutdown fight that followed, with disastrous results for him. Mueller has been a useful villain, with Trump spreading lies and distortions about Mueller’s team and work (for example, calling the group led by Mueller, a lifelong Republican, “13 angry Democrats”).

For all of the effects on political actors, Mueller’s fans in the public might take the loss hardest. For this group, the special counsel has become a figure of messianic importance who will deliver the nation from Trump. Some view his promise in straightforward legal or political terms; some have taken it in stranger directions. In a rather more outré offering, Rachel Dodes wrote in Vanity Fair of having a crush on Mueller. “Beautiful Swan, I have to admit that back in the day, if a soothsayer foretold that I’d fall for the consummate G-man, I would have poured bong water on their head and vomited on their loafers,” she wrote. “Those were different times and, admittedly, I was a fool. In this moment of rampant debauchery and freeloading, your patrician uprightness, by contrast, seems almost radical.”

Despite the years of anticipation, experts predict that Mueller’s report is more likely to be a short summary than a long, devastating narrative à la Bill Clinton adversary Ken Starr. Nor is Mueller likely to stand before the nation and offer a resounding critique of Trump, as then–FBI Director Comey did in July 2016, when he recommended not prosecuting Hillary Clinton over her use of a private email server but criticized her email practices. The conclusion of Mueller’s work will mean a loss of purpose and a new realization of the difficulty of removing a president, no matter how square the lead investigator’s jaw.

There are, however, two groups that will greet the conclusion of Mueller’s work with delight. One is people connected to the investigation who have escaped indictment and can begin to cut down on exorbitant legal bills. The other is the reporters who have been on constant high alert for weeks, expecting a report at any moment. None of the others—not the Democrats, not the Republicans, not Trump, and not the Mueller stans—is likely to feel any kinship with those relieved to see Mueller go.

Cottage cheese faced a problem: After World War II, batches of the soft, lumpy dairy concoction developed a propensity to take on a rancid odor and a bitter taste. That changed in 1951, when dairy researchers identified the culprits, three bacterial miscreants that produced this “slimy curd defect.” To prevent the condition, researchers advised cheesemakers to keep these bacteria from entering their manufacturing facilities in the first place. Thus ended the scourge.

Despite this and other advances in cottage-cheese production, like texture analyzers, high-powered microscopes, and trained human tasters, cottage cheese has never enjoyed the same popularity as yogurt. That’s because cottage cheese, once revered for its flavor and versatility, has taken a series of gut-punches in the dairy sector: enduring associations with weight loss, inconvenient packaging, and near-total displacement by its cousin, Greek yogurt, to name a few. But stalwart food scientists and artisanal dairy farmers have high hopes for the future of cottage cheese. With yogurt sales on the decline, a golden age of curds might be right around the corner.

“It’s a pretty straightforward cheese to make,” says John Lucey, a professor of food science at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Even so, the process is time-consuming and labor-intensive. It begins with creating the curd, the lumpy matter found in cottage cheese.

The curd comes from nonfat milk and added cultures, which trigger the milk’s fermentation. After hours of cooking near room temperature, the milk turns into a gel that is cut into pea-size curds. Cutting the curd releases whey, the liquid that remains after curdling. The fragile curds that result are then washed, to cool them and rid them of excess water and acidity. Finally, a dressing, made from fermented cream, is mixed with the curds. Other ingredients such as stabilizers, gums, and salt are added as needed in large-batch production.

Dave Potter and his wife, Cathy, distribute cultures to artisan cheesemakers and to small- and medium-size dairies. The cultures are bacteria used to ferment the lactose in the milk. “The bacteria are just trying to survive, but we’re using their by-product to produce these foods,” he explains.

Although cultures are used in making both the curd and the dressing, they add little flavor to the final product because they’re killed off during its production. It’s the cream in the dressing that gives cottage cheese its dominant flavor and distinguishes one cottage cheese from another. “There are a lot of people who have their own proprietary way to make the dressing,” says Lucey. Some might be buttery, others tart, for example. How the mixtures are cooked and the origins of the milk and cream also affect the taste and texture of cottage cheese, and ultimately its appeal.

But it doesn’t appeal to many. In the United States, cottage-cheese consumption been in a free fall since the mid-1970s.

Negligence is the reason, says Moshe Rosenberg, a professor of food science and technology at the University of California at Davis. In the last half century or so, yogurt makers have added flavor to their products, while cottage cheese has failed to receive the same treatment. Meanwhile, Americans consume about 15 pounds of yogurt per capita, compared with just two pounds of cottage cheese. “I would dare to say that had there been the same effort to dress up cottage cheese with new flavors and new ingredients, we would see a much higher consumption of cottage cheese,” Rosenberg says. “Cottage cheese has been neglected, and the new king has been crowned.”

[Read: How did Greek yogurt get so popular?]

Already disregarded, cottage cheese faced another setback during the late 1990s: a new zeal for low-fat foods. Creamed anything back then was a “no-no,” Rosenberg notes. Creamed meant fattening, or at least people thought it did. But full-fat cottage cheese is only 4 percent fat. That’s dramatically less than other cheeses like cheddar, which hover around 30 percent.

In industries like salad dressing, Rosenberg explains, a significant reduction in fat content boosted sales. “There was a campaign to introduce what I call cheeseless cheese: cottage cheese that was low-fat or fat-free.”

Rosenberg’s lab spent two and a half years looking at what happens when the fat is removed from cottage-cheese dressing. The results weren’t pretty. “The minute a little bit of cream was taken out of the product, it significantly affected its quality attributes, especially the texture,” he says.

That’s because full-fat cottage cheese allows the cream to cling to the outer surface of each curd particle, which prevents the curd from absorbing the moisture from the dressing. When you eat full-fat cottage cheese, you can feel the curd particles on your tongue and you can taste the cream.

Not so with low-fat and non-fat cottage cheese. The product becomes “pastelike,” according to Rosenberg. Most of the moisture from the dressing gets absorbed by the curd, leaving it very mushy and soft. “This deterioration in the traditional quality of the product turned many people off,” says Rosenberg.

Greek yogurt filled the void left by cottage cheese. Over the last few years, people have been seeking low-fat, high-protein foods, and Greek yogurt offers a tasty, nutritious option for some. But Rosenberg has bad news for them.

A 100-gram serving of full-fat cottage cheese contains 11.5 grams of protein and 4.3 grams of fat. An equivalent amount of full-fat Greek yogurt offers about 25 percent less protein (8.7 grams), but provides almost as much fat (4.1 grams) as the cottage cheese. Low-fat cottage cheese still has a lot of protein (10.5 grams) but only about a gram of fat, whereas low-fat Greek yogurt contains more fat—1.7 grams—for only 8.2 grams of protein.

[Read: There’s something about yogurt ]

Rosenberg shakes his head at Greek yogurt’s figure-defying rise. “Nobody talks about it,” he says, almost as if a conspiracy is afoot, before acknowledging that it’s just marketing. “When there is a campaign to promote a product by building an image around it, miracles can happen, and what we see with the Greek yogurt is a miracle.” Greek yogurt seems sophisticated and cosmopolitan, while cottage cheese remains associated with the tedium of weight loss, not to mention the blandness dieting can imply.

Cottage cheese built that reputation over a long time, and breaking it will be hard. Potter recalls that when he began his career as a dairy producer 30 years ago, cottage cheese was marketed mostly to women, men on diets, and bodybuilders.

The connection between dieting and cottage cheese seems to have endured, even with Millennials. When Rosenberg’s lab needed some cottage cheese for analysis, he asked two students to pick some up at the local supermarket. Both of them refused. To Rosenberg’s dismay, the students didn’t want to risk being seen buying cottage cheese.

Cottage-cheese makers have started offering single-serving packaging akin to yogurt, making the product easier to eat as a snack or on the go. That could help distance cottage cheese from its old-fashioned serving methods, spooned from a large tub and topped with canned peaches, for example. In so doing, the milky curds might shed some of its associations with dieting, too. Rosenberg says he’s puzzled by the lack of marketing for cottage cheese, given its near identical composition to yogurt. He worries that the cottage-cheese industry might have given up, especially given that the big producers can just make yogurt instead.

If that’s the case, why do dairies bother producing cottage cheese at all, anymore? Many don’t, it turns out. Potter estimates that only about two dozen U.S. dairies make the stuff. However, there is a movement among artisan cheesemakers to revive the curd and give yogurt a run for its money.

Maureen Cunnie makes Cowgirl Creamery’s Clabbered Cottage Cheese. It’s a time-consuming artisanal process, but one that yields a product with its own nuanced character. The creamery sources its milk from a local supplier, Bivalve Dairy, about a half-hour’s drive from Petaluma, California, where the cottage cheese is made.

“It’s a very slow set,” says Cunnie, referring to the curd. That allows the milk to develop more flavor, she explains. The milk is separated, pasteurized, and cultured in the afternoon, and allowed to set overnight. The next morning the curd is “cut,” or stirred. “We gently stir the curd over about two hours, and this creates little pillows of curds,” Cunnie explains. “If you stir it too fast, it would shatter, so it’s really a sensory process on the part of the cheesemaker.”

Cowgirl’s dressing is crème fraiche mixed with cultured milk, which Cunnie says gives it a little tang and a little sweetness. “This gives it a much richer presence in your mouth,” she says.

[Read: How to stop hating your least favorite food]

Last year, the dairy industry reported a slight slowdown in the sale of Greek yogurt. That might be good news for Cunnie and her fellow curdmasters. Potter, who eats cottage cheese straight from the container, thinks yogurt’s popularity has peaked. He also sees large-batch cottage-cheese makers putting more effort into the consistency of their respective brands’ taste and quality.

He’s also seeing more single-serve packaging with a greater diversity of products and flavors. Potter thinks that trend is the most important for increasing cottage-cheese consumption. Lucey agrees. “You don’t get a five-pound tub of yogurt and say, ‘There you go, John, there’s your lunch,’” he says.

But its proponents still hope that the intrinsic properties of cottage cheese might win people over. For starters, Rosenberg says, forget about the low-fat and no-fat variations. Embrace full fat, instead. After all, it’s still just cottage cheese. “People don’t think twice when they go and buy fries or cheeseburgers,” he says. “But when it comes cottage cheese, and they see the words full fat, they get cold feet. ‘Oh, no, no, this is pure poison!’”

“Just cottage cheese” isn’t enough for Potter. He has greater gustatory aspirations for these lumpy curds of soured milk. “You have to make it accessible to everybody and convenient and not just plain cottage cheese. People are looking for flavor, and a little excitement.”

Anthony Bouchard, who often sports a waxed handlebar mustache that recalls the outlaws of the Wild West, has a habit of showing up at public events where everyone is unarmed and explaining that they’re in danger. In 2011, as the executive director of the hardline Wyoming Gun Owners, he attended a Casper City Council meeting with a handgun holstered at his hip. “Law-abiding citizens aren’t the ones you have to worry about,” he said. The council subsequently banned guns in city meetings.

In 2017, as a freshman state senator, Bouchard confronted three African American students about their presentation on gun violence and race at a University of Wyoming symposium. “He was quite menacing and threatening,” Allison Gernant, the students’ instructor, told me. “There were scare tactics. Like, he said, ‘I’d like to bring a bomb onto campus and set it off and see how long it would take for the UW police to get there.’” (Bouchard accused Gernant of “political race baiting to promote gun control” and described her account as “FAKE NEWS.”)

Bouchard is on a mission to eliminate “gun free zones” in his state, and the University of Wyoming is a top target. In 2017, he introduced a bill that would allow students to carry concealed weapons on campus. It failed, and this year he reintroduced it as part of a broader bill expanding liberties for gun owners. This time, rather than emphasizing the hypothetical dangers of an unarmed campus, he pointed to the precedent of other campus-carry states, such as Utah. “They’ve been doing it for 20 years, and it works,” Bouchard told local journalists. The bill lost a Senate committee vote in January, but gun rights activists in Wyoming aren’t giving up on the issue.

“It’s all the same arguments every time we have any kind of gun bill,” Bouchard lamented after the bill failed in the Senate. “The sky was going to fall, danger’s happening. It’s all the same argument, and it’s emotional. They’re not looking at the reality.”

This is a common refrain among campus-carry advocates. In the six states where such laws have been proposed this year, supporters have argued not so much that it’s necessary to protect students, which is a hard sell, but that it has proven harmless in the states where it’s allowed in some form. In West Virginia, the state director of the NRA said that in states with campus carry laws, “once the hypersensitivity of the issue subsided, there’s been absolutely no problems.” In Florida, a state representative told the Orlando Sentinel that “none of the things university presidents said would happen [actually] happened.”

I teach at the University of Texas at Austin, where campus carry was implemented two and a half years ago. At the time, newspaper reporters and TV crews from as far away as Tokyo covered the massive protests on our campus, which featured the spectacle of thousands of students waving dildos (because Texas regulates sex toys more rigorously than firearms). Since then, many have claimed that campus carry has worked out just fine. “Concealed carry poses no danger on Texas college campuses,” Governor Greg Abbott tweeted. “The dire consequences never happened.”

Could it be that, despite all the agita in academia, campus carry has turned out to be no big deal? That depends on how you measure its impact. There has not been an outbreak of gun-related violence at schools in campus-carry states, but that was never opponents’ main worry. Rather, they’ve argued that the presence of guns on campus would end up costing millions of dollars and would negatively affect schools in less quantifiable ways—impacting pedagogy, institutional reputation, campus atmosphere, and the recruitment and retention of faculty and students.

The evidence to support those warnings is growing, and there may well be fatal consequences that few foresaw.

Three decades after he penned the Second Amendment, James Madison served on the six-member board that banned students from carrying guns and ammunition on the University of Virginia campus. Thereafter, guns were prohibited at American institutions of higher education as a matter of course. That all changed in 2004, when the state legislature in Utah passed a law that stripped public colleges of the authority to establish their own policies about firearms. The new law wasn’t precipitated by any particular event; there hadn’t been any mass campus shootings in the state, nor any recent high-profile college shootings anywhere else in the country. (The 1966 sniper attack at UT Austin was by then a distant memory.) The University of Utah fought in court for the right to set its own firearms policies, but lost.

Other states did not immediately follow suit. But in 2007, the Virginia Tech massacre led to the formation of the group now called Students for Campus Carry, which quickly gained membership and attention nationwide. With support from SCC—and, to a lesser extent, the NRA—dozens of campus-carry bills were introduced in statehouses over the proceeding decade, many only passing after a second or third legislative session. Other states, such as Colorado and Oregon, adopted campus carry when universities lost court battles with gun rights advocates. Today, a complex patchwork of state laws makes it difficult even to say with clarity how many “campus carry” states there are. (Eleven have permissive laws similar to Utah’s; 16 ban guns completely; and 23 at least nominally allow guns on campus, but with more stringent restrictions and various caveats.)

The ostensible goal of campus carry was to empower armed civilians on college campuses to defend themselves and others from mortal danger. That has not yet happened. “Campus carriers have not intervened in any incident anywhere in the country on a campus,” said Stephen Boss, a professor of environmental dynamics and sustainability at the University of Arkansas.

For his new book, College Homicide: The Case Against Guns on Campus, Boss examined every campus homicide in the United States between 2001 and 2016. He found no direct interventions by campus carriers, and no deterrent effect. Murders are rare on campuses that allow concealed carry, but no rarer than on college campuses where guns are banned. “Utah did pretty well for eight years,” he said, “and then a student shot himself [in the leg] at Weber State University in 2012, and then in 2016, ’17, and ’18, the last three years consecutively, there’s been a murder with a gun on the campus of the University of Utah, Salt Lake. So their luck’s run out.”

In 2015, during the one-year window the Texas legislature allotted schools to prepare for campus carry, UT Austin hosted two public forums about the implementation. At one of these, I testified that the university should develop a protocol about what to do with guns left behind in bathroom stalls. (Should we bring them to lost and found? Call the police? Put an “out of order” sign on the door?) People laughed. A year later, students left guns in the women’s bathrooms here twice in the same week. According to The Campaign to Keep Guns Off Campus, similar incidents have happened in Georgia and repeatedly in Kansas. And where there are guns, there will be accidents: An Idaho State professor shot himself in the foot during class, and an employee at the University of Colorado in Denver was trying to un-jam her gun when it went off, injuring herself and a coworker.

In addition to dealing with such accidents, campus-carry schools have spent millions adapting their physical infrastructure (installing gun safes, signage and metal detectors, for example), retraining staff, and replacing faculty members lost to attrition. Other instructors have changed their teaching practices by eliminating discussions of sensitive subjects that might raise tempers in the class, or by offering courses exclusively online, or even by holding office hours in bars or churches where guns are prohibited, rather than meet with armed students in their offices.

And then there’s the matter of campus suicide.

The late Allan Schwartz, a professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Rochester, studied college suicide for the better part of two decades. In 2013, he published an article comparing suicide rates among college students with nonstudents. Using nationally representative data from 2007, he found that, among men age 18-24, the suicide rate was much lower—about half—for those enrolled in college. This, despite that fact that students and nonstudents attempt suicide at roughly the same rate (1.4 percent versus 1.8 percent).

Schwartz considered various parameters that could account for the disparity, and became increasingly convinced that the single most consequential factor was access to guns. Students who lived on campus had a lower risk of suicide than those who lived off campus; those who were enrolled full time had a lower risk than those enrolled part time; those who stayed on campus continuously had a lower risk than those who went home for the weekends, and so on. The more time that students spent in an environment where guns were prohibited, the less likely they were to die by suicide.

Which wasn’t surprising to mental health professionals. Decades of public health research have repeatedly demonstrated that access to guns increases the likelihood of a death by suicide. This is because over 80 percent of people who attempt suicide with a gun die as a result—compared to less than 2 percent of those who use other common means, such as overdosing. And most people who attempt suicide and survive never make another attempt.

“We have no reason to think that the same sort of pattern wouldn’t happen on college campuses that happens off college campuses—the more guns that are present, the higher the rates of suicide,” said Marjorie Sanfilippo, a psychologist at Eckerd College in Florida. To compare suicides at campus-carry schools and schools that prohibit guns, Sanfilippo has begun to survey the directors of college counseling centers across the country. So far, the results are stark: The campus-carry schools had significantly higher rates of both attempted and completed suicides. Sanfilippo acknowledges that her sample size thus far is very modest—just 22 respondents. “Of course, each one represents thousands of students,” she said. She is planning to expand the scope of her research.

Large-scale research projects cost money, though, and when it comes to gun violence, the federal purse strings have been drawn tight for decades. Congress first threatened to defund the Centers for Disease Control in 1996 if it recommended any form of gun control. President Obama issued an executive order in 2013 instructing the CDC to identify priorities for gun violence research, and still the agency demurred. (Obama did get his report, but it was published by the National Research Council and was essentially an analysis of past research—much of it decades old.) Language in last year’s government spending bill softened the threat that gun research could imperil the agency’s budget for injury prevention, but until funds are specifically allocated for gun research, the roadblock remains.

As long as the CDC avoids gun-related research, the institutions best equipped to study the issue are research universities, and they’re about to receive a huge injection of funding for that express purpose. Over the next five years, the National Collaborative for Gun Violence Research plans to distribute up to $50 million from the RAND Corporation, specifically for academic research into gun violence. Sanfilippo is among the many researchers applying for support.

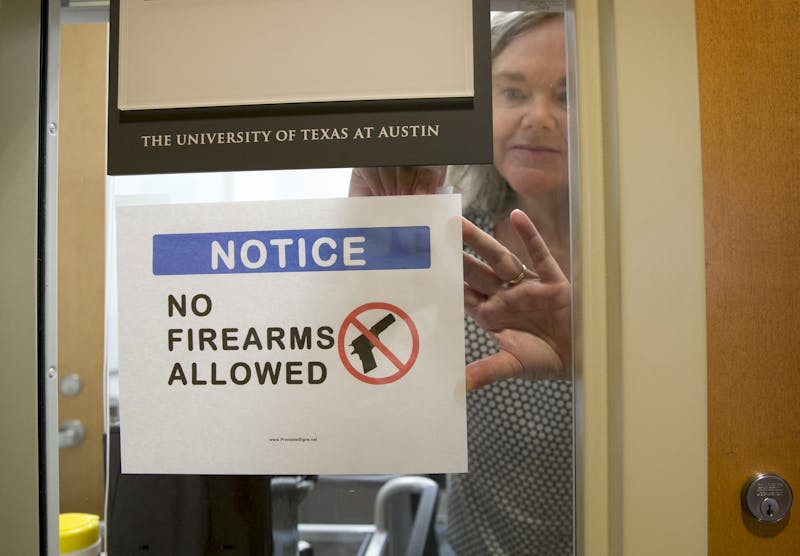

Meanwhile, where campus carry has already been enacted, schools adapt. In 2016, UT Austin implemented a policy that allows faculty and staff members to prohibit guns in our offices. But we’re only permitted to convey this rule verbally; we can’t hang a sign saying, “No guns allowed.” So my colleague George—her nickname, as she resembles the Beatle—came up with a work-around, which required the use of my 9mm Beretta semiautomatic pistol.

Initially, I thought it would only be the two of us at target practice. But by the time I’d secured permission to shoot on private property just outside town, three other women had asked to participate: a UT administrator, a graduate student visiting from another institution, and Ana Lopez, an undergraduate student who co-founded Students Against Campus Carry. She’d become a public face of the resistance to campus carry, profiled in The New York Times and invited to the White House to meet with then–Vice President Joe Biden. She’d also been accused by gun rights advocates of not having the authority to debate campus carry because she didn’t have experience shooting guns. She intended to negate that line of criticism by getting some range time.

As we bumped along a dusty road in the Texas Hill Country, the struts of my Volkswagen hatchback bucking under the weight of five passengers, four guns, and several boxes of ammunition, I was tempted more than once to call it off. Putting a gun in a student’s hands seemed so obviously inappropriate that it needn’t even be mentioned in the university’s handbook of conduct. Or it used to seem that way, anyway.

George had brought her doctoral diploma, also from UT. With binder clips, we fixed it to a target in front of an earthen berm, along a creek lined with Texas live oaks. It hangs now in her office, where visitors ask about the bullet holes between the lines of calligraphy—a prompt to discuss her office gun policy, in lieu of an overt sign.

When Ana’s turn came to shoot, I made her pause a moment as I checked again that the backdrop was clear. I glanced around to confirm everyone was wearing their ear plugs and safety goggles. “Okay,” I finally said. “Disengage the safety.”

What could possibly go wrong?