Report: Michael Avenatti Stiffed Paraplegic Man out of $4 Million Settlement

Embattled lawyer Michael Avenatti reportedly stiffed a paraplegic man with mental health problems out of $4 million personal injury settlement,Read More

Preempt Threats and Safeguard America's National Security with USIntelNews.com

Embattled lawyer Michael Avenatti reportedly stiffed a paraplegic man with mental health problems out of $4 million personal injury settlement,Read More

President Donald Trump ridiculed some Democrats for turning on their former hero Special Counsel Robert Mueller.

Pop icon Elton John has joined calls for a boycott of hotels owned by the Sultan of Brunei after theRead More

Unplanned’s success is yet more proof that the fascist establishment no longer has the ability to control the flow ofRead More

Superheroes to Rescue as Theaters Tussle With Small Screens… (Third column, 10th story, link) Related stories:Sad ‘DUMBO’ Disappoints at BoxRead More

Toward the end of Sally Rooney’s new novel, Normal People, Connell, an aspiring writer, assures his girlfriend, Marianne, a politics student, that the woman he was speaking with at a party the night before “wouldn’t be remotely my type.” Marianne replies with a banality that she acknowledges as banal: “you can never know another person, and so on.”

Yeah. Do you actually think that, though?

It’s what people say.

What do I not know about you? he says.

Marianne smiles, yawns, lifts her hands in a shrug.

People are a lot more knowable than they think they are, he adds.

True enough, though it depends on who’s doing the knowing, doesn’t it?

In every generation, there are writers who speak for that generation, who bottle some essential current or mode of thinking and being, and arrange it in letters on the page. The 28-year-old Rooney has been hailed, not implausibly, as “the first great millennial author.” Her debut, Conversations With Friends, was as star-making as White Teeth and as zeitgeisty as Less Than Zero. Rooney, who is Irish, has an uncanny sense of how people under 35 talk and text, how they use the internet, how they voice their passionate yet casual Marxism, how it feels to come of age after the 2008 crash. She has a knack for dialogue, a faultless grasp of pacing, and the ability to situate the reader instantly in a place and a feeling. But what makes her a great novelist is her freakish psychological acuity. She has a keen eye for the desires and anxieties expressed in everyday behavior—how someone holds a coffee stirrer, or “presses his hands down slightly further into his pockets, as if trying to store his entire body in his pockets all at once.” Her books are like strangely pleasurable medical exams, in which she opens her characters on the table and goes over their insides with a scalpel.

The word that gets used to describe Rooney’s style is “spare.” Her paragraphs are built for the Instagram age. They are plain as white walls, empty rooms with one beautiful accent, like a potted fern. She brings an early-dawn feeling to the subject of human intimacy—usually portrayed as messy and chaotic—and an analytic philosopher’s interest in clearing away problems, in scrubbing things down to their parts, so that they can be built anew. Her images are striking, and her wit subtle and dry; the reader doesn’t share the jokes as much as she admires them. “Cherries hang on the dark-green trees like earrings,” thinks Connell at one point. “He thinks about this phrase once or twice. He would put it in an email to Marianne, but he can’t email her when she’s downstairs.”

Many good writers and all the great ones have only one story to tell, even if they find different ways of telling it. With Rooney this is especially pronounced. Conversations With Friends was the story of two university students, Frances and Bobbi, who are ex-girlfriends and best friends. They become entangled with a thirtysomething couple, Nick and Melissa; Frances and Nick have an affair. The plot was old—naïve young woman falls in love with broken married man, heartbreak and suffering ensue—but the novel felt entirely new. It’s fitting that Rooney’s subject is love—the thing that has been done countless times by others, but can only be felt by each person as if it were the first time for anyone, because, for that person, it is.

Normal People, too, is the story of first love. Connell and Marianne come from Carricklea, way out in the provinces of west Ireland. She is rich, and he is poor; his single mother cleans Marianne’s house. Marianne is unpopular and brilliant and has been physically and emotionally abused by her family for years. Connell is a popular and good-looking soccer player who reads The Communist Manifesto at night. In their last year of school, they begin a secret sexual relationship that continues, on and off, through their years at Trinity College.

Normal People has the feeling of having been either rushed into publication following the success of Conversations With Friends or a draft for Conversations With Friends. It’s most useful to read them together, as one book or project. The female protagonists in both novels are extremely thin, neurotic geniuses with at least one terrible or outright abusive parent. They physically suffer and seek out forms of pain. They ask men to hit them during sex. Their male love interests are athletic, a little passive, smart enough to understand how smart the women are, and perceptive enough to find them beautiful. They are also handsome—the kind of objective, ridiculous good-looking that, “even covered in blood . . . radiates good health and charisma,” and obviates the need to find any other reason for desiring them. Both books involve close intimacies between a poor person and a rich person. In both, the poor person is recognized as a literary talent and writes a short story, which immediately leads to professional reward and the ascent up a rung in the literary world, while the rich person accepts a more humble fate.

The biggest difference between the two books is that Conversations With Friends is set in the past tense, told by a first-person narrator (Frances), and Normal People is in the present, with alternating third-person narrators. Where one would expect a present-tense narration to be more comedic and quicker, Normal People is slower, and sadder. It gives us no sense of Marianne or Connell in the future, or how their later adulthood inflects their memories. The book doesn’t look back at youth, it looks out from it. Rooney’s interest in this time of life has less to do with the irony that characterizes novels like Sentimental Education or The Age of Innocence and more to do with a sincere and documentary parsing of confusions and discoveries. In some ways, this gives the reader less to hold on to, and the book threatens to slip from memory in much the way that one’s own youth does. The power of Normal People is that, without the presence of a compromised thirtysomething character like Nick, the book speaks entirely without regard for middle age, insisting, rightfully, on the truth of its own time.

Economic anxiety blows like a sharp wind through Rooney’s world. Her characters know they won’t have pensions and that jobs are hard to come by. Frances, who at one point is too broke to buy groceries, is judgmental of Melissa and Nick’s large house and easy lifestyle but admits that she was seduced by them, too. “I wasn’t trying to trash your life,” she tells Melissa in a rare moment of disclosure. “I was trying to steal it.” In Normal People, Connell’s life changes when he wins a scholarship. His rent is paid, and he can afford to take a trip through Europe with his friends. “Suddenly he can spend an afternoon in Vienna looking at Vermeer’s The Art of Painting, and it’s hot outside, and if he wants he can buy himself a cheap cold glass of beer afterward.” How elegantly Rooney interweaves consciousness and place; suddenly the reader is seated in a sunlit café, beverage in hand, feeling the condensation running down the side. Connell steps into a world that had looked like “a painted backdrop,” and he can’t believe it can bear his weight, his inclusion. “That’s money, the substance that makes the world real. There’s something so corrupt and sexy about it.”

In a bildungsroman, the hero is supposed to find his social footing, to be educated into adulthood, and take his place in society. But for many, education means moving out of one world and into a no-man’s land, some kind of limbo. In college, the previously awkward and despised Marianne ably navigates social hierarchies, while Connell flails. Through his connection with Marianne, he is accepted as “rich-adjacent: someone for whom surprise birthday parties are thrown and cushy jobs are procured out of nowhere.” He has nothing in common with these people, and he can’t really speak to them at all. Their parents caused the financial crash. They don’t care about doing the reading or studying. They spout off opinions in class, and stand around comparing their families’ wealth. He won the scholarship, but he doesn’t belong. “I just feel like I left Carricklea thinking I could have a different life,” he says to the college mental health counselor when he crashes into a major depression. “But I hate it here, and now I can never go back there again.”

Rooney is a keen observer of class and its behaviors— Marianne’s creepy boyfriend Jamie gets worked up over drinking champagne out of coupe glasses, which only shows what a Philistine he is. But manners per se are not her concern. Sociological rituals and class behavior provide the background for devastating summations—executions, really—of motive and psychology. “Connell always gets what he wants, and then feels sorry for himself when what he wants doesn’t make him happy,” Marianne thinks. Or this:

Jamie is somehow both boring and hostile at the same time, always yawning and rolling his eyes when other people are speaking. And yet he is the most effortlessly confident person Connell has ever met. Nothing fazes him. He doesn’t seem capable of internal conflict. Connell can imagine him choking Marianne with his bare hands and feeling completely relaxed about it, which according to her he in fact does.

Rooney narrates very plainly, allowing the rhythm of what looks like ordinary speech to build, until she introduces a startling fact or perfect image. Her language is effortless, never overwrought. “The sky is a thrilling chlorine-blue, stretched taut and featureless like silk.” Her descriptions of emotions can be bluntly accurate—“Marianne felt a relief so high and sudden that it was almost like panic”—or evocative—“He carried the secret around like something large and hot, like an overfull tray of hot drinks that he had to carry everywhere and never spill.” She can even make a pathetic fallacy work: “Outside her breath rises in a fine mist and the snow keeps falling, like a ceaseless repetition of the same infinitesimally small mistake.”

“Eventually Nick looked over and I looked back,” she wrote in Conversations With Friends. “I felt a key turning hard inside my body, turning so forcefully that I could do nothing to stop it.” This is perfect, heart-stopping, and simple. We speak all the time in the cliché of someone “unlocking” this or that inside of us. All Rooney has done is take that familiar language and alter it a little, and by doing so, emphasized the passivity of the lock. It’s a small and exact moment, and her novels are filled with ones like it. She writes about sex with the same care and attention and plainness that she writes about everything else. “He touches his lips to her skin and she feels holy, like a shrine.” And then, the words that everyone has said to someone, somewhere, so bare and final: “It’s not like this with other people.”

As an investigation of sexual power dynamics, Normal People goes further, or into more specifics, than Conversations With Friends did. Marianne’s relationship is defined by her desire to submit to Connell, a desire of which they are both aware. At first this manifests as her willingness to keep their attachment secret, to never speak to him in the hallway or tell a living soul about what they do after school hours. (She knew from the start that “she would have lain on the ground and let him walk over her body if he wanted.”) Connell senses immediately that Marianne would never break their confidence, which is both intoxicating and disturbing. Marianne is comfortable in secrecy, which is to say that she is used to being bullied.

In Conversations With Friends, the intensity—the truth—of love is also wrapped up with the woman’s willingness to do anything for the man. “You can do whatever you want with me,” Frances says to Nick. The women show their love by making themselves vulnerable, which puts the man into a bind: Act on it, hit the woman, let her feel how much she will give herself, and you’re a sadist; don’t, and she feels exposed and judged, rejected. When Marianne is not with Connell, she seeks out joyless sexual relationships where she, too, asks men to do whatever they want to her. With unethical actors, her submissiveness provokes cruelty. “She’s conscious by now of being able to desire in some sense what she does not want,” Rooney writes. “The quality of gratification is thin and hard, arriving too quickly and then leaving her sick and shivery.”

Sex creates privacy. It divides the world: the things we do out there, and the things we do in here. But the privacy of Connell and Marianne’s relationship surpasses that usual division. Its privacy is rooted in shame. When, after a juvenile miscommunication, Connell withdraws from the relationship, he pursues something more “normal”—which is to say, something containable, something social. He finds that with Helen, a normal medical student who does normal things: She goes to the gym, posts photos of her friends on Facebook. It’s easy for Connell to walk down the street holding her hand. There are people you would die for and other people that you can live with, and they are not always the same people. Connell’s love for Helen doesn’t cut to his marrow; it leaves him alone.

“Normal” is a word that comes up a lot in Rooney. “Things matter to me more than they do to normal people,” Frances thinks. Rooney imagines neurotics and writers on the one hand, women who want to be hit during sex and don’t eat enough, and on the other, the people who go to work and don’t obsess for hours over whether to send an email. But more is at stake than feeling like you don’t fit in with the jocks. At one point, Bobbi explains to Frances that she’d like to get a job in a university. “I just don’t see you as a small-jobs person,” says Frances. By “small jobs” Frances means “raising children, picking fruit, cleaning.” Such occupations feel like disappointments, comedowns, anti-creative, as opposed to what she had expected—that Bobbi would smash global capitalism, burn bright. Bobbi explains that she’s “just a normal person.” If Frances needs to see her otherwise, that has more to do with Frances than with her.

The history of the novel is full of characters who mature by reconciling themselves to a more limited and circumscribed fate than they had felt entitled to. In interviews, Rooney speaks openly about her discomfort with receiving media attention for writing novels, and her wish that nurses and bus drivers would be profiled, instead. In her books, however, rich characters accommodate themselves to their inability to change the world, and poor characters pursue an artistic vocation with optimism and openness to the future.

Normal People’s version of this moment occurs at a protest against the war in Gaza. Marianne, who is in the crowd, experiences both the desire for revolution and her own disappointment at being no longer able to believe in such revolution. She suddenly grows up.

Marianne wanted her life to mean something then, she wanted to stop all violence committed by the strong against the weak, and she remembered a time several years ago when she had felt so intelligent and young and powerful that she almost could have achieved such a thing, and now she knew she wasn’t at all powerful, and she would live and die in a world of extreme violence against the innocent, and at most she could help only a few people.

The education that all Rooney’s characters undergo involves the embrace of personal attachments. They give up seeing themselves, if they ever really did, as individual agents and accept their dependence on each other. This, in some ways, is the traditional work of the novel—to solve a political conflict through romance—but in Rooney the attachments are unconventional. No one settles on a traditional relationship. Things are open. Her characters are aptly designed for such experiments. They are well-meaning and progressive. If they do unkind things, they have some good reason for it, and they apologize. Her minor characters—villains—might be petty or have bad politics (centrists), but her protagonists lack spite and bile. They are unable to hold a grudge.

Normal People ends sweetly. It’s presumed that Connell will be leaving Dublin for New York, but Marianne, who can’t be more than 21, approaches this departure with gracious nostalgia and generous sangfroid. There is no accusation of betrayal, and we are not permitted to find Connell’s action selfish or cruel. “People can really change one another,” is how the book ends. “You should go, she says. I’ll always be here. You know that.” Rooney’s vision of intimacy and romance is fundamentally redemptive. Her young students have not been ruined by the world, and still believe in changing it—a few people at a time.

On-screen eagles lock talons in aerial combat, and humpback whales engulf herring by the shoal. Birds of paradise, hunting dogs, leafcutter ants—they’re all there. This is Our Planet—Netflix’s new, big-budget nature documentary—and, without the sound on, viewers could easily think that they’re watching Planet Earth III.

The resemblance to the oeuvre of the BBC’s renowned Natural History Unit is striking. The series is produced by Alastair Fothergill, who was also responsible for the original Planet Earth. Everything is narrated by David Attenborough, whose unctuous tones, somehow both silky and gravelly, have become synonymous with wildlife films.

But this time, the messages delivered by that familiar voice are different. Here, much of the awe is tinged with guilt, the wonder with concern, the entertainment with discomfort.

Repeatedly, unambiguously, and urgently, Our Planet reminds its viewers that the wonders they are witnessing are imperiled through human action. After seeing a pair of mating fossas—a giant, lemur-hunting, Madagascan mongoose—we’re told that the very forests we just saw have since been destroyed. After meeting endearing orangutans Louie, Eden, and Pluto, we are told that 100 of these apes die every week through human activity. We see Borneo’s jungle transforming into oil palm monocultures in a time-lapse shot that is almost painful to watch. We’re told that Louie and Eden’s generation could be the last wild orangutans.

If you muted the series, it would look almost identical to any other wildlife documentary. You could sit back, content and relaxed, gawping at nature’s splendor. But Our Planet seems to have no interest in letting you be contented. Though still entertaining and beautiful, its narration impart its shots with a more complex emotional flavor. It’s like watching an American drug ad, where a voiceover reads out lists of horrific side effects over footage of frolicking, picnicking families.

Frankly, it’s about time.

The BBC’s natural history series have been a gift, enchanting tens of millions of viewers with nature’s wonders. But the shows have also been criticized for whitewashing the decline of the creatures they feature. Disappearing species, shrinking habitats, spreading diseases, accumulating pollutants, changing climates: Planet Earth obliquely hinted at these problems in its final line. “We can now destroy or we can cherish: The choice is ours.”

Read: Planet Earth II[ puts stunning images above all else]

Frozen Planet, a tour of polar fauna, saved its talk of climate change for its final seventh episode—and Fothergill says he had to fight for even that. “There has been a habit of having a 45-minute show where we say that everything’s fine, and in the last five minutes, we say there’s a problem,” he told me. “I think that’s a little bit trite. It doesn’t deal with the issue.”

After Planet Earth II repeated some of these problems, the natural history film producer Martin Hughes-Games wrote that, by showing a pristine world, without context, these series are “lulling the huge worldwide audience into a false sense of security.” The rejoinder has always been that warnings would dissuade viewers. “Every time that image [of a threatened animal] comes up, do you say ‘Remember, they are in danger’?” asked Attenborough in an interview with The Observer. “How often do you say this without becoming a real turn-off?”

The answer from last year’s Blue Planet II—still the greatest nature series of all time—was: At least once an episode. The answer from Our Planet is: Repeatedly, in shot after shot. It does what no other natural history documentary has done. It forces the viewer to acknowledge their own complicity in the destruction of nature—in the moment. It feels sad, but also right.

That’s not to say that Our Planet is a dour, finger-wagging downer—far from it. It is hard not to cheer as an initially incompetent Philippines eagle takes her first flight, or laugh as a treeshrew uses a pitcher plant as a toilet, or marvel at two Arabian leopards meeting and mating—one percent of the surviving individuals, perhaps creating a few more. We’re treated to a rare glimpse of the oarfish—a luminescent, serpentine creature that looks like it has swum out of mythology. We witness the improbably complex dance of the western parotia—a bird of paradise that almost single-handedly justifies the entire group’s name. Most of the series is still joyful, but it is never allowed to be naively so.

“The only reason I worked on this project was that, from day one, conservation was part of it,” says Sophie Lanfear from Silverback Films, who produced the second episode about polar life. “It had to be the heart of every episode.” This commitment is framed from the opening seconds of the first episode, as the camera pans over the pockmarked surface of the Moon to reveal the Earth, and Attenborough intones:

Just 50 years ago, we finally ventured to the Moon. For the very first time, we looked back at our own planet. Since then, the human population has more than doubled. This series will celebrate the natural wonders that remain and reveal what we must preserve to ensure that people and nature thrive.

That remain! What you’re seeing is what is left to see.

The message is clear. It’s bad. It’s urgent. It’s our fault. We can still fix it. Our Planet is a eulogy, a confession, a slap on the wrist, a call to arms. (The task of offering actionable advice is outsourced to the series’ website.)

Read: [What scientists learned from strapping a camera to a polar bear]

There is optimism, too. Amid doom-laden warnings, it highlights success stories where conservation measures have allowed species to start bouncing back. When we watch five cheetah siblings do their best lion impressions and cooperatively bring down a wildebeest, Attenborough tells us that we get to enjoy such dramas only because the Serengeti has been protected for decades. And in a sequence of unexpected poignancy, wild horses, foxes, and wolves are seen thriving among the ruins of Chernobyl, the radiation a minor inconvenience compared to the boon of human absence. “In driving us out the radiation has created space for wildlife to return,” Attenborough says.

The series isn’t faultless. Some episodes still feel as disjointed as those of Planet Earth II did, with few narrative threads connecting the individual sequences. There are a few minor but weird mistakes: Orangutans are described as our ancestors when they’re our distant cousins, and phytoplankton are called plants when most are nothing of the kind. And the score never goes for a subtle musical cue when a saccharine one will do.

But these are minor gripes for a series that audaciously treads where its predecessors have feared, and sets the bar for its successors. “Five years ago, when we started on this journey, it was always hard to get environmental programming onto primetime,” Fothergill says. “That’s definitely changed. Even the BBC are now saying that they want environmental messaging in their programs.” While seeing elephants, we will finally hear about the elephant in the room. And not a moment too soon.

A former ESPN writer has penned a new book in which he claims that President Trump is a notorious cheat,Read More

TEL AVIV – Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro professed his love for Israel in Hebrew as he was greeted by PrimeRead More

On this weekend’s broadcast of Fox News Channel’s “Sunday Morning Futures,” Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) offered a glimpse into PresidentRead More

Pro-Life ‘UNPLANNED’ Surprise Opening… (Third column, 13th story, link) Related stories:Superheroes to Rescue as Theaters Tussle With Small Screens…Sad ‘DUMBO’Read More

BREXIT BREAKDOWN: What will May do if her deal goes down again? (Third column, 14th story, link) Related stories:Cabinet Cracking…Read More

Pope defends decision to keep French cardinal after cover-up… (Third column, 20th story, link) Advertise here

In August, the most important Islamic religious council in Indonesia, home to the world’s largest Muslim population, issued a public health opinion. The Indonesian Ulama Council, known as the MUI, decreed that observant Muslims in the country should consider the measles vaccine haram, or forbidden, because it contains gelatin derived from pork.

The fatwa represented a niche opinion—millions of observant Muslims accept vaccines every year—but it had the power of politics behind it: The head of the MUI, a religious hardliner, had recently agreed to appear on the ballot with Indonesia’s president when he runs for reelection in April. The ruling had disastrous consequences. Millions of parents in Indonesia refused to allow their children to be vaccinated, and the region of Aceh, which operates under religious law, blocked vaccination teams from entering. Outside of Java, Indonesia’s most populous island, the refusals pushed vaccine acceptance to just 68 percent of eligible children, when effective protection requires 95 percent. In Aceh, only 8 percent of children received the shot.

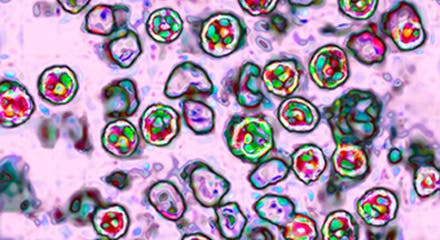

The opposition to the measles vaccine in Indonesia surfaced the same month that the Italian Senate voted to end all mandatory vaccinations for schoolchildren—for measles, tetanus, polio, and seven other diseases. By October, the occurrence of measles—one of the most contagious diseases on the planet and a widespread cause of blindness, deafness, and brain damage—began rising there. Simultaneously the disease soared across Europe, with 82,596 cases in 2018, compared to 5,273 two years earlier. Measles also crept back in Venezuela, just two years after the Americas had been declared free of the disease. At the end of November, an array of international health authorities—the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, UNICEF, and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance—jointly warned that measles was surging across the planet. “We risk losing decades of progress,” a WHO official said.

The worldwide effort to eliminate measles is not failing because the organism has changed significantly—the virus that infects a child today is largely the same one that sickened children 100 years ago—nor because the vaccine is faulty. Measles cases are multiplying across the globe for the same reason that the international campaign to eradicate polio has stalled, and that Ebola outbreaks continue, and that opportunistic new diseases like Zika take us by surprise: a rise in nationalist politics, which is causing countries to turn inward, harden their borders, and distrust outsiders. One hundred years after the influenza pandemic of 1918—the worst outbreak in recorded history, which killed as many as 100 million people by some estimates—the assumption that every nation owes an investment in health to every other nation no longer holds.

As nativist appeals undermine public health systems and cooperation among countries degrades, the potential for catastrophe increases. We are always at risk of a new disease breaking out, or a previously controlled one surging back. What’s different now is that the rejection of scientific expertise and the refusal to support government agencies leave us without defenses that could keep a fast-moving infection at bay. Pathogens pay no respect to politics or to borders. Nationalist rhetoric seeks to persuade us that restricting visas and constructing walls will protect us. They will not.

“Nationalism, xenophobia, the new right-wing populism in Europe and the United States, are raising our risk,” said Ronald Klain, who was the White House Ebola response coordinator for President Barack Obama and now teaches at Harvard Law School. “There’s a focus not so much on stopping infectious diseases as much as there is on preventing the movement of people to prevent the transmission of diseases. And that’s not possible, because no matter what you do about immigrants, we live in a connected world.”

Distrust of expertise, suspicion of immigrants, shunning of international cooperation—these all describe nationalist movements in Africa and Europe. But the place where official attitudes toward global public health have changed most sharply is the United States during the presidency of Donald Trump. It’s difficult to convey just how great the change has been over the past two years. The Obama administration wrote the first national strategy to tackle antibiotic resistance in 2014, launched with an executive order and a summit at the White House; created the Global Health Security Agenda, which drew 64 nations into a partnership to advance public health; and oversaw the largest foreign deployment of the CDC in the agency’s history, to the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa—which was accompanied by an emergency appropriation of more than $5 billion. The Trump administration has abandoned such commitments.

Trump’s first budget proposal included sharp cuts to the CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the Environmental Protection Agency, which is responsible for addressing the health problems caused by climate change. The final budget passed by Congress reinstated much of the funding for these agencies, but Trump’s next budget proposal a year later included further cuts to health and science. Beyond the budget cuts, Trump also drastically reduced the scale of the CDC’s overseas outbreak-prevention work from 49 countries to ten and attempted to eliminate $252 million in funding left over from the Obama administration’s appropriation for Ebola. Moreover, Trump dismantled the National Security Council’s global health security team, leaving the United States with no clear channel to respond to global health threats.

The Trump administration’s dismantling of public health protections should come as no surprise. In the summer of 2014, shortly after the start of the Ebola outbreak, Trump—not yet a candidate—demanded that the United States close its borders against the disease. “Keep them out of here,” he tweeted about American missionaries who fell ill in West Africa. “Stop the Ebola patients from entering the U.S.” and “The U.S. cannot allow Ebola infected people back.” In July 2015, a month after he declared his candidacy, he made an explicit association between immigrants and disease in a statement about his views on Mexico. “Tremendous infectious disease is pouring across the border,” he said.

By that fall, Trump’s views on the value of public health spending had come to dominate political discourse. Zika, the mosquito-borne virus that causes grave birth defects, began to spread within Puerto Rico in December 2015, and the next month a baby was born in Hawaii with Zika-related microcephaly, the first signs of a multiyear outbreak that’s produced more than 43,000 confirmed diagnoses in the United States and its territories. In February 2016, President Obama sent an emergency request to Congress for $1.8 billion in funding to help fight the disease. The Republican-led Congress cut the request by $700 million, however, and then took 233 days to approve it. “That delay was driven, in no small part, by a baseless view that Zika was a disease being brought to our country by immigrants,” Klain said. “As a result, you had local transmission of Zika in Florida in 2016. You had for the first time in our country’s history the Centers for Disease Control issuing a travel advisory against part of the continental United States.”

Two weeks before last year’s midterm elections, as a migrant caravan made its way through Central America toward the U.S. border, the idea of immigrants posing a health risk to the American populace emerged again. “It’s a health issue, too, because we don’t know what people have coming in here,” Fox News host Laura Ingraham said on October 23. Two days later, a guest on her program raised the issue as well, saying, “We have mass amounts of people coming into our country with disease.” Fox & Friends next picked up the theme of disease-bearing immigrant hordes, followed by a Lou Dobbs guest on the Fox Business Network who linked “the continued invasion of this country” with “diseases spreading across the country that are causing polio-like paralysis of our children.” The most explicit outburst of this rolling moral panic probably came from David Ward, a former U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent who claimed on the Fox News show Your World with Neil Cavuto, “We have these individuals coming from all over the world that have some of the most extreme medical care in the world, and they are coming in with diseases such as smallpox and leprosy and TB that are going to infect our people in the United States.”

These assertions are either flatly false (smallpox was declared eradicated in 1980) or grossly inflated (roughly 34,000 cases of leprosy, now called Hansen’s disease, occurred in the Americas in 2015, 94 percent of which were clustered in Brazil—not the source of the caravan). Ironically, the caravan members might well have posed less of a risk to the American public than other U.S. residents do, because the countries from which they were fleeing have higher routine vaccination rates than those recorded in many parts of the United States. But even after the midterms, Fox News hosts and guests continued to promote the idea that immigrants to the United States were bringing with them the seeds of the next great pandemic. At the end of November, Fox & Friends First co-host Jillian Mele announced the network had “exclusively” found “serious health risks being carried by some of those migrants”—risks that, according to correspondent Griff Jenkins, included lice, chicken pox, and the common cold. And in December, in the infamous White House press briefing in which he promised to “take the mantle” of shutting down the government, Trump reemphasized the now-familiar point: “People with tremendous medical difficulty and medical problems are pouring in, and in many cases it’s contagious. They’re pouring into our country. We have to have border security.”

The claim that immigrants are intrinsically dangerous long antedates Trump’s rise to power. Indeed, it was the justification for U.S. immigration restrictions for more than a century. “Whether we’re talking about the Irish during the great cholera epidemics of the antebellum period, or polio and the Italians, or tuberculosis from the Jews, or bubonic plague and the Chinese, it’s a recurring concern that Americans have,” said Alan Kraut, a professor of history at American University and the author of Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the “Immigrant Menace. “The popular theme is they are ‘dirty,’ and a challenge to the public self.”

But nationalists who blame immigrants for bringing illnesses across U.S. borders are looking in the wrong place. A two-year project headed by University College London and The Lancet, published in December, found no evidence that the arrival of migrants endangers a nation’s health. (In fact, because migrants often go to work in medicine and as personal care attendants, they typically enhance a country’s health.) The more likely Patient Zeros are the people who are neither suspected nor checked: the citizens, legal residents, businesspeople, and tourists—227 million just in 2017—who fly unimpeded between the United States and other countries. The legal movement of people, and the shipment of food and freight, have already transported dangerous pathogens into—and out of—the United States: highly drug-resistant gut bacteria in a child returning from the Caribbean to Connecticut; treatment-resistant TB in an attorney who caught the disease in the United States, traveled to his destination wedding in Greece, and then returned home to Atlanta; foodborne illness on spices grown in Asia and mixed into charcuterie in Rhode Island.

In fact, migrants remanded into federal custody at the U.S. border seem likely to be facing graver health threats than the ones they would have encountered in their home countries. “I don’t hear much about efforts in the tent cities we’re building on the border to ensure that everyone’s got access to clean water and clean food and adequate ventilation to prevent transmission of respiratory disease,” said Peter Jay Hotez, founding dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine. In December, two Guatemalan children died in Border Patrol custody.

This is the perverse legacy of nationalism in power: By stigmatizing immigrants and segregating them, xenophobia can turn the lie of the “dirty foreigner” into truth.

The Trump administration’s neglect of America’s public health infrastructure is risky twice over: It courts outbreaks at home, and it weakens commitments that the United States—in fact, most governments—have made to public health around the world. The immediate aftermath of World War II saw a great upsurge of international collaboration on public health. The World Health Organization was founded in 1948, and an intensive multinational effort to eradicate smallpox—one of the deadliest killers in history—began in 1967. Leaders of the new global health regime developed complex surveillance systems and vast vaccination campaigns that they shared across borders. Their efforts soon met with success: Smallpox was declared eradicated in 1980, the first time in history that a deadly disease was effectively eliminated, and rinderpest, a cattle disease, followed it to extinction in 2011. The nationalist upheavals occurring across the globe now signal a potentially disastrous retreat from that confident cooperation.

“The greatest public health success happens in the context of social modernism, this legacy of the Enlightenment that history moves toward inevitable progress,” said Katherine Hirschfeld, an anthropology professor at the University of Oklahoma and the author of Gangster States: Organized Crime, Kleptocracy, and Political Collapse. “The political support for that has waned, and will probably continue to wane as we move into a darker era.”

Before the present crisis, we had ample warning that nationalist disputes could ruin public health achievements. Consider one instructive augur: Back in 1988, a punishing conflict broke out between two Soviet republics—Armenia and Azerbaijan, whose Nagorno-Karabakh region voted to unify with Armenia. The war ruined the economies of both, impaired their public health systems, displaced more than one million people—and led to the return of malaria, which a strict Soviet mosquito control program had suppressed for 50 years. By 1996, two years after the conflict ended, the number of malaria cases in Azerbaijan had surged to 13,135. The number of cases in Armenia peaked at 1,156 in 1998. It took more than a decade of eradication efforts—an aggressive program of spraying for mosquitoes and hunting down swamps and pools of stagnant water where the insects breed—to get the disease back under control. Malaria was not banished again from Armenia until 2011. Azerbaijan was declared malaria-free in 2013.

The Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict set an ominous precedent. The same year the former Soviet republics launched hostilities, global health officials announced a campaign to permanently contain the spread of polio. Scientists confidently predicted that they would end transmission of the disease by 2000. It was a worthy goal; polio had mostly been chased from the Americas—the last case was in 1991—but was still paralyzing 350,000 children a year around the world. However, the campaign to destroy polio also proved a collateral casualty of nationalist unrest. In 2003, Muslim religious leaders in Nigeria, which then harbored 45 percent of all polio cases in the world, declared that the vaccine was religiously unacceptable, halting vaccination efforts in three states where the disease was clustered.

The move was nominally doctrinal—based on the same concern over vaccine ingredients that arose in Indonesia last year—but actually political. National elections had just transferred the center of power from a longstanding military regime with roots in the Muslim-majority north to a democratic one originating in the Christian-dominated south. Jockeying in the aftermath stirred up rumors and conspiracy theories—including some alleging that the polio campaign, led by Western nations, had deliberately contaminated the vaccine in a plot to wreck the fertility of Muslim girls. Only intensive diplomacy from other African and Islamic countries brought the disaffected states back into line behind the anti-polio campaign. But the new accord came too late; polio surged back. By 2006, Nigeria harbored four out of every five polio cases left in the world, and the disease had spilled across its borders to infect almost 1,500 children in 20 countries that had previously vanquished polio. Thanks to the worldwide movement of observant Muslims during the annual hajj, the Nigerian strain was carried to Saudi Arabia. From there, it spread as far as Indonesia.

And polio is still not done. After pushing back the target date for eradication several times, the international campaign adjusted the time line yet again in January, extending it through 2023 and warning that even that goal may prove elusive. Wild polio virus remains entrenched in just two countries, Afghanistan and Pakistan, but vaccine-derived virus—a condition arising from a mutation in the vaccine strain and spread by low rates of vaccination that leave children vulnerable—persists in Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique, Niger, Papua New Guinea, and Somalia. In January, several groups that are part of the 31-year-old campaign to eradicate polio urged the international community to push harder toward achieving their goal. “This is an effort that cannot be sustained indefinitely,” they warned.

In almost every case where polio persists, the same geopolitical backstory has enabled its survival, with ethno-nationalist and religious forces setting out to destabilize a dominant government. That’s been the case for the Taliban and Pashtun tribal members in Afghanistan and Pakistan, as well as for Boko Haram and tribal minorities in Nigeria. “The most important lesson we’ve learned is that if you intend to eradicate a disease—or at least achieve a high level of control of one—you should be thinking about how you engage ethnic and religious communities country by country, right from the start,” said Stephen Cochi, a senior adviser to the director of the CDC’s Global Immunization Division, which leads the agency’s polio eradication efforts. “Or history will repeat itself, and you’ll hit political or religious, ethnic, or ethnocentric obstacles that are inevitable.”

Undermining public health doesn’t require the involvement of a religious authority. Political disruption will do. That’s visible not just in the United States, but also in the increase in depression and chronic illnesses in eastern Ukraine, where about 1.5 million people have been displaced by ongoing tensions with Russia; the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in war hospitals in Yemen; the collapse of the health care system and spikes in infant mortality in Venezuela; and the staffing crisis in the British health care system triggered by the Brexit vote to withdraw the United Kingdom from Europe.

Perhaps the starkest example of how nationalist politics systematically undermines public health comes from Italy. Giuseppe Conte’s recently elected right-wing government acted with swift dispatch to target the country’s mandatory child-vaccination program. The reactionary Five Star Movement included opposition to vaccines in its campaign platform; after it won almost one-third of the vote last March, it formed a government with the far-right Northern League. One of the new coalition’s earliest official acts was to suspend the requirement that parents present proof of vaccinations against ten childhood diseases before their children can be enrolled in school.

In part, this policy arose from the spreading popularity of vaccine denialism, predicated on the now thoroughly debunked assertion that the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine is linked to autism. Even more, though, Italy’s anti-vaccine politics seems to stem from a broader rejection of expert opinion, based on lingering public outrage over the fallout from the 2008 economic collapse. In December, the new coalition’s health minister dismissed all 30 members of its expert advisers group, known as the Higher Health Council. The country’s chief research scientist, head of its National Institute of Health, quit in protest, telling a national newspaper, “Representatives of the government have endorsed … frankly anti-scientific positions.” (In March, faced with what health officials termed a “measles emergency,” the Italian government reversed course and banned unvaccinated children from attending school.)

As in the U.K., where measles is also rising, the new Italian government is skeptical of cross-border collaboration—before the election, the Northern League proposed withdrawing from the European Union—and profoundly anti-immigrant. Those are all of a piece. “Nationalist movements are based on the rejection of expertise; they build divisions based on prejudice, and mainstream anti-science movements,” said Alexandra Phelan, a faculty research instructor at the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University. “They are intertwined, and they all undermine global public health. No matter how strong a government’s rhetoric about sovereignty, pathogens do not respect, nor care for, country borders.”

No matter where it has surfaced, the nativist assault on public health is gaining traction—and as it does, protections against deadly diseases weaken. The world is interconnected—by legal travel, by the flow of refugees and migrants, by goods and commerce, by the movement of animals and water and air. Any of those channels can carry diseases. None of them has ever successfully been blocked. The only defense is to shore up public health, not destroy it. We are all holding the safety net for one another, and when we let it drop, none of us is safe.

America’s turn toward nationalism does not make the country stronger or safer; rather, it makes the nation more vulnerable to global health threats. Already, Trump’s xenophobic policies have begun to drive even those who have entered the country legally away from public health programs. In November, the nonpartisan organization Children’s HealthWatch reported that for the first time in ten years fewer families of legal immigrants were using food stamps, otherwise known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program—a government benefit they are legally entitled to. That finding bore out a 2017 report from San Francisco that new applications to California’s food stamp program were declining, while families already legally enrolled in the program were dropping out.

The California research and the national study both blamed the drop in legal food stamp use on immigrants’ fears that the government would target them for using a public program. The Trump administration lent credence to such fears in a policy announcement last September: If people seeking U.S. residency used public assistance programs, then Citizenship and Immigration Services would score that against them when their applications for green cards came under review. Afterward, organizations working with undocumented immigrants said the rule change was having a broader chilling effect—as it was likely designed to do. The nonprofit Fiscal Policy Institute estimated that 24 million legal residents, including nine million children, would be affected.

The rule change reaches beyond anti-hunger programs to threaten the immigration applications of people using Medicaid, which guarantees health care to low-income residents, and Medicare Part D, which helps make prescription drugs more affordable. The move drew forceful protests from a wide array of medical organizations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American College of Physicians. They said the rule change would keep adults and children from seeking care they need, either to keep from getting sick or after they had fallen ill, making them more expensive to care for.

That could mean, for instance, that a woman with a breast lump or a man in the early stages of heart disease might postpone getting checked out at a point when such conditions could be treated with less expense and risk. But it might also mean that both legal and illegal immigrants would avoid getting treatments such as flu shots or childhood vaccinations that would help prevent the spread of infectious diseases. In other words, Trump’s new policy would not only deprive visa applicants and legal residents of protection. By driving victims underground, it could turn them into an unwitting vector that could spread disease back to people who think they have made themselves safe by forcing immigrants away.

“The more that we drive up the rhetoric so that people who are now in this country feel threatened by national policy, the more we stand the chance of having a separate society that doesn’t come into the health care system,” said Thomas Inglesby, the director of the Center for Health Security at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “So even as we strive to have strong public health systems and to get people vaccinated and to have early reporting on infectious diseases, that wouldn’t touch this separate group.”

And thus an ominous dynamic lurches into gear: The more any part of the public distrusts the country’s health care system and is discouraged from participating in it, the more vulnerable the health of the entire public becomes. The 2017–2018 flu season killed 80,000 Americans, according to the CDC, making it the deadliest flu outbreak in decades. “Imagine if there were an event in the future where smallpox was released, or if there were a severe influenza,” Inglesby said. “We don’t want a group of ostracized folks on the margins who can’t get access to vaccines, or to whatever the countermeasures are for whatever the threat of the future might be.”

Last year, Inglesby’s group at Johns Hopkins ran a daylong simulation of the world’s likely response to the outbreak of a fictional previously unknown pathogen, one for which there would be no diagnostic test and no vaccine. In a finding that grimly foreshadows the risk of repudiating the protection of public health, Inglesby’s team recorded a worldwide death toll of 150 million, including 15 million deaths in the United States.

It’s Friday, March 29.

‣ Linda McMahon, a former pro-wrestling executive and the current head of the Small Business Administration, will reportedly resign from her position to chair President Donald Trump’s super PAC, America First Action.

Here’s what else we’re watching:

Will the Public Ever See the Mueller Report?: Attorney General William Barr said he plans to share with Congress Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report by mid-April, if not sooner. In his letter to Senator Lindsey Graham and Representative Jerry Nadler, heads of Congress’s two judiciary committees, Barr also said that he will not share the contents of the report with the White House before releasing it, and noted that his summary of the findings from last week was “not an exhaustive recounting” of Mueller’s report, which is nearly 400 pages long.

But that doesn’t mean the public will see the review in full, reports Natasha Bertrand. “Between the withholding of grand-jury and privileged material and the redaction of classified information, the public could be left with a shell of the original report.”

Listen to this week’s episode of Radio Atlantic, in which the staff writers Edward-Issac Dovere and McKay Coppins discuss what all this means for 2020.

Remember the Pee Tape?: Many of the president’s critics were disappointed last week when Barr declared that Mueller’s investigation all but cleared the president of wrongdoing. But the “seeds of the disappointment” were planted two years ago, when BuzzFeed News first published an unverified—and unverifiable—dossier compiled by the British-intelligence operative Christopher Steele, argues David Graham. The salacious document “set the stage for the political response to investigations to come—inflating expectations in the public, moving the goalposts for Trump in a way that has fostered bad behavior, and tainting the press’s standing.”

Call Me a Socialist!: Joe Sanberg, a multimillionaire investor, might be running for president. Sanberg supports Medicare for all, the Green New Deal, increased regulation, and expanding the social safety net. He has no name recognition, but in an election where Trump has painted the Democrats as radical socialists, Sanberg thinks he has an edge: “Good luck to them if they want to call me a socialist, because businesspeople aren’t socialists,” he told Edward-Isaac Dovere.

— Elaine Godfrey and Madeleine Carlisle

Three-year-old Ailianie Hernandez waits with her mother, Julianna Ageljo, to apply for the nutritional-assistance program at the Department of Family Affairs in Bayamón, Puerto Rico. The island’s government says it lacks sufficient federal funding to help people recover from Hurricane Maria amid a 12-year recession. (Carlos Giusti / AP)

Barbara Bush’s Long-Hidden ‘Thoughts on Abortion’ (Susan Page)

“In 1980, when George H. W. Bush was making his first bid for the presidency, Barbara Bush covered four sheets of lined paper with her bold handwriting, then tucked the pages into a folder with her diary and some personal letters. She was trying to sort out what she believed about one of the most divisive issues of the day.” → Read on.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Is Confusing Taxpayers (Mark Mazur)

“Although the most recent IRS data show that average income-tax refunds are closely tracking the average refund from last year, taxpayers have been complaining in interviews with journalists and on social media that their refund is smaller than expected or that they unexpectedly owe additional tax. Given that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was all about tax cuts, how can this be?” → Read on.

Quit Harping on U.S. Aid to Israel (James Kirchick)

“U.S. assistance to Israel demands far less—in both blood and treasure—than many other American defense relationships around the world.” → Read on.

‣ An Awkward Kiss Changed How I Saw Joe Biden (Lucy Flores, New York)

‣ Our President of the Perpetual Grievance (Susan B. Glasser, The New Yorker) (? Paywall)

‣ Former Trump Family Driver Has Been in ICE Custody for 8 Months (Miriam Jordan, The New York Times) (? Paywall)

‣ Is Pete Buttigieg a Political Genius? (Alex Shephard, The New Republic)

‣ The Blue State Trump Thinks He Can Flip in 2020 (Alex Isenstadt, Politico)

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily. Comments, questions, typos, grievances and groans related to our puns? Let us know anytime here.

Were you forwarded this newsletter? Sign up for our daily politics email here. We have many other free email newsletters on a variety of other topics. Find the full list here.