'Get Serious and Stop Rewarding Illegal Immigration,' Border Patrol Agent Says to Congress

Border Patrol Agent Hector Garza told Fox News that Congress needs to “get serious and stop rewarding illegal immigration.” HisRead More

Border Patrol Agent Hector Garza told Fox News that Congress needs to “get serious and stop rewarding illegal immigration.” HisRead More

BORIS ON DECK FOR UK PM… (Third column, 9th story, link) Advertise here

HORROR: Animals Slowly Starve in Abandoned Spanish Zoo… (Third column, 17th story, link) Advertise here

In 1980, when George H. W. Bush was making his first bid for the presidency, Barbara Bush covered four sheets of lined paper with her bold handwriting, then tucked the pages into a folder with her diary and some personal letters. She was trying to sort out what she believed about one of the most divisive issues of the day.

She was sure to be asked what she thought about abortion, and she wanted to have an answer.

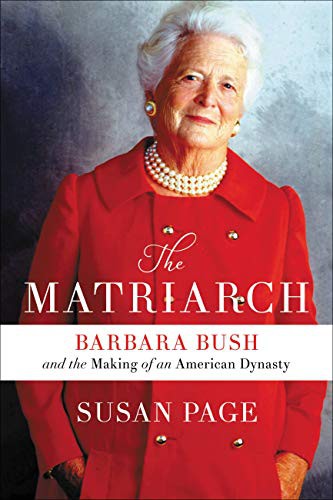

The former first lady never released the pages or detailed the reasoning she outlined in them, not in hundreds of interviews she gave over the decades that followed nor in her two memoirs. But in February 2018, two months before she died, she gave me permission to read her diaries as I researched a biography of her. (The Matriarch: Barbara Bush and the Making of an American Dynasty is being published by Twelve on April 2.) She had donated the diaries to the George H. W. Bush Presidential Library, in College Station, Texas, with the restriction that they be held private until 35 years after her death—as it turns out, until 2053. Only the historian Jon Meacham had been given permission to see them before, when he was working on Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush.

When I began reading her diaries, she and I planned to have another interview, our sixth, in March 2018. (I was allowed to read her papers and to make notes, but not to photograph them.) But she fell the night before and ended up in the hospital; she never recovered enough for us to meet again before she died, a month later. I never had a chance to ask her about what I found.

As I worked my way through an archival box filled with accounts of her endless, exhausting campaign travel that year, I pulled out the yellowing pages, unfolded them, and discovered what was in effect a conversation with herself.

“Thoughts on abortion,” she wrote across the top of the first page, underlining the words.

Her deliberations might astonish cynics who assume that, for those who operate in the world of elective office, the calculations on such contentious topics are always political. The notes provide a window into how seriously she took the issue, and how she saw it as a moral question. The careful thought process they reflect may be the reason she never wavered in her views.

Her husband would, modifying his stance on abortion after Ronald Reagan chose him as his running mate at the Republican National Convention that summer. Before then, George Bush had tried to navigate a position down the middle. He opposed abortion but also opposed passing a constitutional amendment to ban it. He was against federal funding for abortion in general but supported exceptions in cases of rape or incest, or to preserve the health of the mother.

When Reagan asked him to join the GOP ticket, though, Bush promised to support the party platform, which endorsed a constitutional amendment that would overturn the 1973 Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision recognizing abortion rights. By 1988, when Bush was the presidential nominee himself, the GOP platform would go even further. It asserted that “the unborn child has a fundamental individual right to life which cannot be infringed.”

Barbara Bush had no reservations about embracing her husband’s positions on the economy and foreign affairs, and most of all about extolling his virtues as a person and a leader. But on cultural and social issues, she often found herself at odds with the GOP and its increasingly conservative tilt. “In all our years of campaigning, abortion was the toughest issue for me,” she said later.

At the 1980 Republican convention, in Detroit, when George Bush’s prospects to be picked as Reagan’s running mate seemed to have faded, Barbara Bush arrived at a luncheon hosted by the National Federation of Republican Women sporting a pro-choice button. With her husband’s political ambitions apparently vanquished, she felt free to make her own stance on the issue clear.

That burst of independence was over almost before it began. That night, after negotiations with former President Gerald Ford to join the ticket collapsed and Reagan tapped Bush, her pro-choice button disappeared. She didn’t change her views, but she did stop talking about them, saying that only the opinion of those on the ballot mattered. While many assumed she still supported abortion rights—a reassuring thought to some moderate and liberal Republicans—she would rebuff attempts by reporters and activists to engage publicly on the issue until she published her White House memoirs 14 years later.

“Both George and I felt strongly about our positions but respected each other’s views; there was no point in discussing it every time it came up,” she wrote in 1994, in Barbara Bush: A Memoir. While she said the law permitting abortions had been “abused” and called the number of abortions “unacceptable,” she added, “For me, abortion is a personal issue—between the mother, father, and doctor.”

It was in this early memo that she crystallized the issue in her mind.

“When does the soul enter the body is the #1 question,” she wrote. “Not when does life begin, as life begins in a flower or an animal with the first cell. So the question is does the life begin (soul entering the body) at conception or at the moment the first breath is taken? If the answer to that question is at conception, then abortion is murder. If the answer to that question is the moment the first breath is taken, then abortion is not murder.”

As with many profound questions, she thought about the lessons she had taken from the life and death of her daughter Robin. Her beloved 3-year-old had died of leukemia in 1953, after six months of brutal treatments and dashed hopes. The tragedy would shape everything from Bush’s views on big issues to her impatience with prattle.

“What does Barbara Bush feel about abortion,” she wrote in the memo, referring to herself in the third person. She decided that Robin had answered the question she posed.

Judging from both the birth and death of Robin Bush, I have decided that that almost religious experience, that thin line between birth, the first breath that she took, was when the soul, the spirit, that special thing that separates man or woman from animals + plants entered her little body. I was conscious at her birth and I was with her at her death. (As was G.B.) An even stronger impression remains with me of that moment, 27 years ago [when she died]. Of course, extreme grief, but that has softened. I vividly remember that split second, that thin line between breathing and not breathing, the complete knowledge that her soul had left and only the body remained.

She had sensed Robin’s soul entering her body at the moment of her birth, she decided, and she had felt it leave her at the instant of her death.

“What do I feel about abortion?” Bush continued in her distinctive handwriting, almost no words crossed out or reconsidered. “Having decided that the first breath is when the soul enters the body, I believe in Federally funded abortion. Why should the rich be allowed to afford abortions and the poor not?” She said she could support limits on the timing of abortions—“12 weeks, the law says”—but she wrote it was “not a Presidential issue,” underlining not twice. “Abortion is personal, between mother fathers and Dr.”

She considered what public policies might make sense. “Education is the answer,” she wrote. “I believe that we must give people goals in life for them to work for—Teach them the price you must pay for being promiscuous.”

Along the side margin of the last page, she wrote, “Needs lots more thought.”

Andrew Bacevich skewers Robert Kagan’s recent essay about “resurgent authoritarianism” that I commented on earlier:

First, please note that “The Strongmen Strike Back” dusts off and repackages a line of argument made by Kagan and other neoconservatives after 9/11 to promote a Global War on Terrorism. What we have here is bad whisky sporting a new label. Perhaps readers are not supposed to notice, but at least some will recall the disastrous consequences that ensued when Kagan last demanded concerted action to purge the world of evil.

Second, Kagan’s insistence on assigning a common label to the regimes of Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, Nicolas Maduro, Mohammed bin Salman, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, et al‚—suggesting that they are devoted to a common cause and subscribe to a common worldview—is sheer nonsense. Contemporary authoritarianism does not derive from or express anything remotely like an ideology. Its origins are as disparate as its manifestations. It is not one thing, but many things.

Everything Bacevich says about the essay is right, and it lines up with many of the points I made in my post from earlier this month. Kagan’s essay is an ideological statement and a call to arms to justify an expansive and aggressive U.S. foreign policy. It is not an accurate description of the state of international politics, nor is it a useful analysis of authoritarian regimes, but then it isn’t meant to be either of those things. The point of the essay is not to understand or explain the many different kinds of nationalist and authoritarian populism that are cropping up around the world, but to use them as a bogey to frighten people into subscribing to confrontational policies in several regions around the world. Kagan’s crusading ideology requires a grand enemy to crusade against, and when there isn’t one available it has to be cobbled together from whatever happens to be available.

Earlier this year, Damir Marusic carefully picked apart Kagan’s ideas for expansive, aggressive foreign policy in his excellent review of The Jungle Grows Back:

And so the book ends up in much the same place as every other liberal world order sermon: The ideological struggle of our time is between the forces of light (the liberal followers of Enlightenment principles) and the forces of darkness (the obscurantist reactionaries to that tradition). Americans, the purest children of the Enlightenment, may think the struggle has long ago been won, but they are wrong—as wrong as the naifs who refused to confront illiberalism in the 1930s.

As I said back in January, “Hegemonists like Kagan need a big enemy to justify the incessant meddling abroad and the exorbitant military budgets that they already support,” and he has conjured up a new monster to destroy with his “resurgent authoritarianism” thesis. Hegemonists need a bogeyman, and Kagan has given himself the task of inventing it.

Michael Lind recently made the same point as Bacevich about Kagan’s sloppy use of the term authoritarian to apply to a wide range of regimes:

“Authoritarianism” is a political science label slapped on radically different regimes, not a self-description. There were and are self-conscious Marxist-Leninists and Salafist theocrats. But there is no generic “authoritarian” movement and no common “authoritarian” worldview.

By casting too wide a net, Kagan would have the U.S. confront too many states all at once, and by lumping together disparate regimes he ignores the important rivalries and disagreements among them. Like all ideologues, he places far too much importance on the role of ideology in understanding the behavior of other states, and he urges the U.S. to act against its own best interests in the name of promoting an ideological cause. But then Kagan isn’t interested in getting the details right. He is concerned with producing what Bacevich calls “elegant oversimplification” that provides ready-made excuses for an activist and meddling U.S. role in the world. It is not intended to persuade skeptics, but to reassure the believers that they stand at Armageddon and battle for the Lord. Unfortunately for Kagan’s intended audience, the idol they worship is a false one and will continue to fail them.

Mohammed Amanullah didn’t have to look up the number for the 106th Precinct in Queens. Looking out the window of his home on Glenmore Avenue, he realized he didn’t even need to call: A patrol car was already stationed outside Al Furqan Jame Masjid, an Ozone Park mosque.

It was March 15, and news had broken of a massacre at two mosques in New Zealand. Amanullah, the mosque’s general secretary, was worried about copycats.

The fear was hardly unwarranted. Nine days later, on March 24 in Escondido, California, an arsonist set fire to a mosque with seven worshippers inside. There were no injuries, but the authorities found graffiti left by the arsonist citing the deadly assault on the mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand.

As a result, the New York Police Department patrol car was back at the mosque in Ozone Park.

“We worry because we got the hate already,” Amanullah said in an interview this week.

Amanullah was referring to August 2016, when the imam at Al Furqan Jame Masjid, Alauddin Akonjee, was shot to death just blocks from the mosque. Another man walking with the imam was killed, as well. Amanullah had prayed with Akonjee the morning before the killing. Amanullah said he was eating lunch at home when his brother called with news of the murder.

“I said: ‘What are you talking about? You got the wrong news. I just got out of the mosque; I pray with him,’” Amanullah said. When he realized it was true, he said, “I sat down like a dead man.”

There are few mosques in America, then, where the fear of violence is more acute. And lasting. Last year, as part of our Documenting Hate project, we spent time at the Ozone Park mosque and with the widow of the slain imam. The gunman had been captured and convicted of the two murders, but there had been no formal hate crime charges, something that felt unjust to the imam’s wife, Minara, and her children. For Minara, there was no question about the gunman’s motive: Her husband had been targeted because of his faith.

“Why else would anyone attack my husband?” she said to us last year.

Mdabdul Halim, the current imam at the mosque, said the New Zealand massacre seemed to register most alarmingly with his older congregants. The accounts of the killings made clear that escaping the gunman’s onslaught was difficult. One woman was reported to have been killed while shielding her husband, who was in a wheelchair.

“If someone attacked like that on us, what would they do?” Halim asked about his older worshippers.

For those who pray at Al Furqan Jame Masjid, it can sometimes feel impossible to escape the specter of menace.

Shaheed Vazquez, a worshipper there, is a corrections officer. After the 2016 murder, Vazquez found himself working in a Brooklyn detention facility and charged with assisting in the guarding Oscar Morel, the imam’s killer.

“It was a little unnerving, but you have to treat everyone the same,” he said.

Vazquez said he was shaken anew by the massacre in New Zealand and the suspected arson in California.

“You don’t know if it’s going to be a series,” he said.

Ozone Park is a wildly diverse and vibrant community of Muslims and Hispanics and African Americans. A statue of the Virgin Mary stands on a lawn across the street from the mosque. American flags fly from the windows and porches of many homes as Middle Eastern singing pulses through the neighborhood at prayer time. Signs stapled to telephone poles and ash trees advertise SAT tutoring in Arabic and English.

An officer at the 106th Precinct said that the police have been commanded to check on the mosque more regularly than usual. During Friday prayer, extra squad cars are dispatched to the mosque.

“We have a great relationship,” said the officer.

The worry about violence, though, can extend beyond the confines and congregants of the mosque. Sandra Peet, 45, who lives next to Al Furqan Jame Masjid, said she has come to fear that she might also be hurt if the mosque is attacked.

“You always have to worry,” said Peet, who said she works as a security guard for the Board of Education. “Always you expect the unexpected.”

An 82-year-old woman who flies a giant American flag on the side of her garden and who gave only her first name, Ann, said she has watched waves of Muslim immigrants move to Ozone Park. She said that she has no problems with her neighbors, but that she knows they can be targets of violence.

“They’re there to stay,” she said. “They’re not running away.”

Hate crimes against Muslims continue to plague New York. They can be individual acts, like the woman wearing a hijab who this year was assaulted or the other woman in a hijab who was spit on in New York City. Or they can be more sinister and sizable, like the arrest in January of three men and a high school student for their alleged role in a bomb plot in the upstate community of Islamberg. The defendants have pleaded not guilty.

In all, the New York Police Department reported 16 anti-Muslim hate crimes in 2018, down from 29 in 2016 but up from 14 in 2017. Last year, the New York chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations said there was a 74 percent increase in “anti-Muslim harassment, discrimination, and hate crimes” in New York state since the 2016 election. And a 2018 New York City Commission on Human Rights survey found that more than a quarter of Muslim Arab hijab-wearing respondents said they’d been intentionally pushed on a subway platform.

At Al Furqan Jame Masjid, the building is now surrounded by cameras, and in a window is a sign with a photo of a camera warning, “ALL ACTIVITIES ARE RECORDED VIDEO AND AUDIO TO AID IN THE PROSECUTION OF ANY CRIME COMMITTED AGAINST THIS FACILITY.”

However, Amanullah would like to see more cameras. He said that at the imam’s funeral, Mayor Bill de Blasio promised to fill the neighborhood with cameras. He is still waiting.

“He told us a lie,” he said bitterly. “We don’t have any security cameras.”

The mayor’s office did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Mike Pecchillo, 32, who said he has lived in the neighborhood all his life, said the anxiety and anger are not hard to understand. He said he had watched the Facebook livestream of the New Zealand massacre and it made him reflect on Ozone Park.

“You do have people who tend to pick on the Muslims,” he said. “You’re gonna have assholes who try to copycat the guy who gets off on the hate.”

On Thursday’s broadcast of CNN’s “AC360,” House Intelligence Committee member Mike Quigley (D-IL) stated that “There is obvious evidence, inRead More

Donald Trump thrilled residents in Michigan on Thursday by announcing support for $300 million for the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative.

Taiwan mulls death penalty for drunk driving… (Third column, 16th story, link) Advertise here

The fast-growing migrant rush over the U.S. border is collapsing border security and overwhelming the ability of border agents to process andRead More

The Illinois Prosecutors Bar Association (IPBA) has condemned Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx for her handling of the JussieRead More

Israelis unveil ‘world’s longest salt cave’… (Third column, 15th story, link) Advertise here

In a matter of weeks, Algerian politics have been upended.

Hundreds of thousands of Algerians—including university students, doctors, and lawyers—began taking to the streets in February, calling for the end of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s rule. Now 82, Bouteflika has appeared in public only a handful of times since suffering a series of strokes six years ago, but he still planned to run for a fifth term as president in national elections scheduled for April 18.

Bowing to public pressure, Bouteflika’s government canceled the polls and installed a new prime minister. The ailing ruler will not run in any future elections. But many Algerians don’t believe the words of officials who for years have effectively been puppets of Bouteflika and his loyalists.

The question now is whether Algeria will undergo a genuine transition of power, Bouteflika and his minions will maintain their grip, or Islamist political factions will strengthen their authority in a country where secularism is strong.

[Read: A chronology of the Algerian war of independence]

I asked the Algerian novelist and journalist Kamel Daoud about what has been unfolding. Daoud is best-known for his novel The Meursault Investigation, a retelling of Albert Camus’s The Stranger told from the perspective of the brother of the unnamed Arab killed by the protagonist of Camus’s 1942 novel.

An outspoken free spirit and a columnist for Le Quotidien d’Oran, an Algerian daily, Daoud has long written that his country deserves better than a choice between military dictatorship and Islamists. A former Islamist himself, Daoud, now 48, has been harshly critical of how conservative religious forces in Algeria have tried to suppress individual liberties and the rights of women—views that are progressive at home but that have also won him fans on the right in Europe.

Daoud lives in Oran, Algeria, but was in Paris when we spoke by telephone. I translated our conversation from French and edited it for length and clarity.

Rachel Donadio: What do you think happens next in Algeria?

Kamel Daoud: It’s hard to know what will happen, because for the moment, the regime isn’t doing much and is trying to buy time. But on the other hand, the Algerians are keeping up the pressure. There are still bigger and bigger demonstrations. For now there’s status quo. The regime is going to try to anticipate things by saying they’ll change the government and carry out reforms and start a national dialogue.

But I think this is the usual strategy that dictatorships turn to when they’re forced to. They try to start a dialogue and reforms, which is what I’d call the first phase. That’s what’s happening now in Algeria. I think the regime pushed Algerians’ sense of humiliation too far. We reached a point of electing a photo, which Algerians can’t tolerate.

There’s an even deeper force: demographics. Half of the Algerian population is under 30. The entire regime is old. The people of the regime are all 85 years old, and sooner or later this generational rupture was bound to cause a crisis. I also think that the generation of the decolonizers has come to an end all over Africa, but it arrived quite late in Algeria. And that was going to have consequences sooner or later.

Donadio: So is this moment of transition also important as a sign of how anti-colonialism has become less strong of a force in Algeria?

Daoud: Yes. For several years now, I’ve tried to write about how to get out of the post-colonial mentality. A lot of people reproached me for this—a lot of people in France and in the United States and elsewhere—because post-colonialism has become a comfort. For years, I’ve been writing about how we need to stop using post-colonialism as a complete and total explanation of reality. I think now we’ve reached a sort of political expression that’s very clear: People want to get out of the post-colonial era. They want to be done with that generation.

[Hassan Hassan: The Arab winter is coming]

Donadio: How is what’s happening in Algeria different from what happened in the Arab Spring in 2011?

Daoud: Because what happened in the Arab Spring in 2011 already happened in Algeria around 1990. In 1988, thousands of young Algerians took to the streets. The army shot on the crowds and killed hundreds of people, and then there was a democratic opening, which the Islamists took advantage of. After that, the military came and took control of everything. So what the rest of the Arab world has been living since 2011, we’ve seen in Algeria since 1988, 1990. That’s why Algeria didn’t follow the wave, because after 1990 we had a very painful civil war and were left on our own, in solitude.

Before the attacks of September 11 in America, few people in the world understood what a jihadist was, what an Islamist was. Now the difference between what’s happening in the rest of the world is that in Algeria, there’s a very clear understanding of the risks of the moment being co-opted by Islamists or the military.

The second thing is that for years, the regime offered us a very clear choice that’s blackmail: Security or democracy? If you want democracy, you’re going to get what happened in Libya and in Syria. And I think that explains why the marches and demonstrations have been so peaceful in Algeria. They wanted to prove to the world and to the regime that they could move without destroying the country. The examples of Syria or Yemen have weighed heavily on the conscience of Algerians. They want change, but they want change without destroying the country.

Donadio: You’ve written for a long time that Algeria deserves better choices than the one between military dictatorship and Islamism. And you recently wrote in Le Monde that the Algerian senate is a “Club Med without an ocean view,” that is, a comfortable spot for Bouteflika’s cronies. What do you think of the possibility of a technocratic government? Could that be a viable option, or is it a bit of a joke?

Daoud: Unless the regime really does something, it’s a joke. Because we’re accustomed to fake national dialogues. We’re accustomed to fake oppositions. The regime has a habit of taking us for fools. That’s why Algerians don’t trust the regime. What Algerians want is a guarantee of change and of transition. They don’t want to negotiate with the regime if it’s going to stay in power. They want to negotiate the exit of the regime. Unless you install a real national transitional council with a leadership that isn’t that of the regime, and unless Bouteflika and especially his men leave, a technocratic government will be absolutely useless.

Donadio: What kinds of figures would you want to see on such a national council?

Daoud: Anyone who represents the currents in Algeria. If the Islamists want to participate to save the republic, they’re welcome, but if they want a caliphate, they’re not welcome. We can have secular people and progressives and conservatives and Islamists and modernists—that’s not a problem. Algeria is a country with a lot of differences, and I think we’d gain a lot if we accepted our differences and tried to find a consensus.

[Read: The museum of colonialism]

Donadio: What would be the most difficult issues on the table? Individual liberties? The rights of women? Religion?

Daoud: I think there are two major factors. First, to declare the end of the FLN, the old party [of Bouteflika] that won the war of liberation. This party must be defeated because it should no longer continue to be business as usual. And the second is the status of religion. Religion must respect secularism in the country. We need to separate the political from the religious. I think those are the two most important things. The third thing is to repair Algerian identity. Arab culture is a beautiful culture, but it’s not an identity; it’s a culture. We need to return to our real identity.

Donadio: What about the economy? The unemployment rate is high. Is the discontent of the people taking to the streets also motivated by economics? Is it the economy or ideology?

Daoud: Both. Because the bulk of the country’s wealth is held by a political class, apparatchiks who take all the country’s money, and there’s enormous corruption. So it’s true that there are economic concerns, but Algeria isn’t a poor country; it’s a rich country. The problem is that the money is poorly distributed.

Donadio : What are the implications of this complicated moment in Algeria for the Maghreb, for Europe, and for the world?

Daoud: Maybe that we can find a world in which we can demonstrate without destruction. That would be a giant step. Millions of Algerians have taken to the streets and there hasn’t been any violence. That’s something very important to convey to the rest of the world. But also that the short circuit between the military and the Islamists maybe doesn’t have to be inevitable.

Donadio: What are your hopes and fears for Algeria in this moment?

Daoud: I have a lot of hope as an Algerian. I’m also very worried that the Islamists might steal our revolution, but I think we still need to try.

Donadio: So you think there’s a risk the Islamists will take the opportunity to reinforce their power?

Daoud: If you’re afraid you might get hit by a car when you walk out of the door of your house, you’d never leave the house. So I think we need to take the risk.

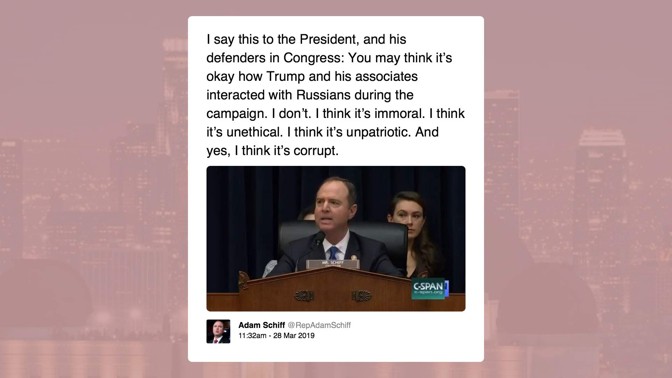

It’s Thursday, March 28. President Donald Trump and the Republicans on the House Intelligence Committee called for Democratic Chairman Adam Schiff to resign, arguing that he “abused [his] position to knowingly promote false information” about the Russia investigation. Schiff hit back:

And the Department of Housing and Urban Development is suing Facebook for allegedly violating the Fair Housing Act. HUD says that Facebook’s advertising tools, which allowed advertisers to restrict an ad’s reach on the basis of categories including race and religion, enabled housing discrimination.

2020’s Mueller Shadow: President Trump wants to shape his presidential campaign around Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s finding that there was no evidence of collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia during the 2016 presidential election. But Republican strategists aren’t sure that’s a good idea. Elaina Plott and Peter Nicholas take us inside GOP discussions over Trump’s campaign for reelection.

Meanwhile, many of Trump’s critics are frustrated that the Russia probe didn’t end his 2020 run. However, Trumpism would still be up for reelection even if the man himself wasn’t, argues Ron Brownstein, and “there’s a far better chance of uprooting [Trump’s] influence over the long run if his presidency is ended by the voters, not the courts or Congress.”

Fly Me to the Moon: Vice President Mike Pence announced this week that the U.S. plans to put American astronauts back on the moon—which no human has visited since 1972—in the next five years. That plan has a couple of holes, writes Marina Koren. How will the U.S. pay for it? During the Apollo program’s peak, NASA’s budget made up more than 4 percent of federal spending. Today it’s less than half a percent. And why go to the moon at all? As Barack Obama said in 2010, “We’ve been there before.”

The Never-Ending Audition: Acting Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan has the dubious honor of being the longest-serving interim head of the Department of Defense ever. Many onlookers thought he’d be the department’s permanent leader by now, writes Kathy Gilsinan, but presidential politics keeps getting in the way.

Lasting Grief: For people affected by mass shootings, trauma can deepen over time, especially around anniversaries of the event—and recovery is often nonlinear. Support for survivors often doesn’t address the complicated realities of grief and trauma, writes Ashley Fetters.

— Madeleine Carlisle and Olivia Paschal

Fans gather outside the Great American Ball Park before an Opening Day baseball game between the Cincinnati Reds and the Pittsburgh Pirates in Cincinnati. (Gary Landers / AP)

The Strange, Unsatisfying End to the Jussie Smollett Case (Conor Friedersdorf)

“Still, so long as hate-crime laws are on the books, there is a strong case for treating hate-crime hoaxes as among the most serious nonviolent crimes.” → Read on.

After Christchurch, Commentators Are Imitating Sebastian Gorka (Graeme Wood)

“A funny thing happened after the tragedy of Christchurch: Everyone discovered, all at once, that ideology matters. Four years ago, commentators were contorting themselves to attribute jihadism to politics, social conditions, abnormal psychology—anything but the spread of wicked beliefs that lead, more or less directly, to violence. Ideology for thee but not for me.” → Read on.

‣ How Donald Trump Inflated His Net Worth to Lenders and Investors (David A. Fahrenthold and Jonathan O’Connell, The Washington Post) (? Paywall)

‣ Betsy DeVos Is Right: Feds Shouldn’t Be Funding Special Olympics (Nick Gillespie, Reason)

‣ How to Confront the Courts (Jesse Williams, Dissent)

‣ Congressional Republicans Have Been Friendly With Nativist Leaders Long Before Trump (Sarah Posner, The New Republic)

‣ Beto O’Rourke Is Genuinely Inauthentic (Christian Schneider, The Bulwark)

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily. Comments, questions, typos, grievances and groans related to our puns? Let us know anytime here.

Were you forwarded this newsletter? Sign up for our daily politics email here. We have many other free email newsletters on a variety of other topics. Find the full list here.

A new press release from the National District Attorneys Association calls out Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx for her roleRead More